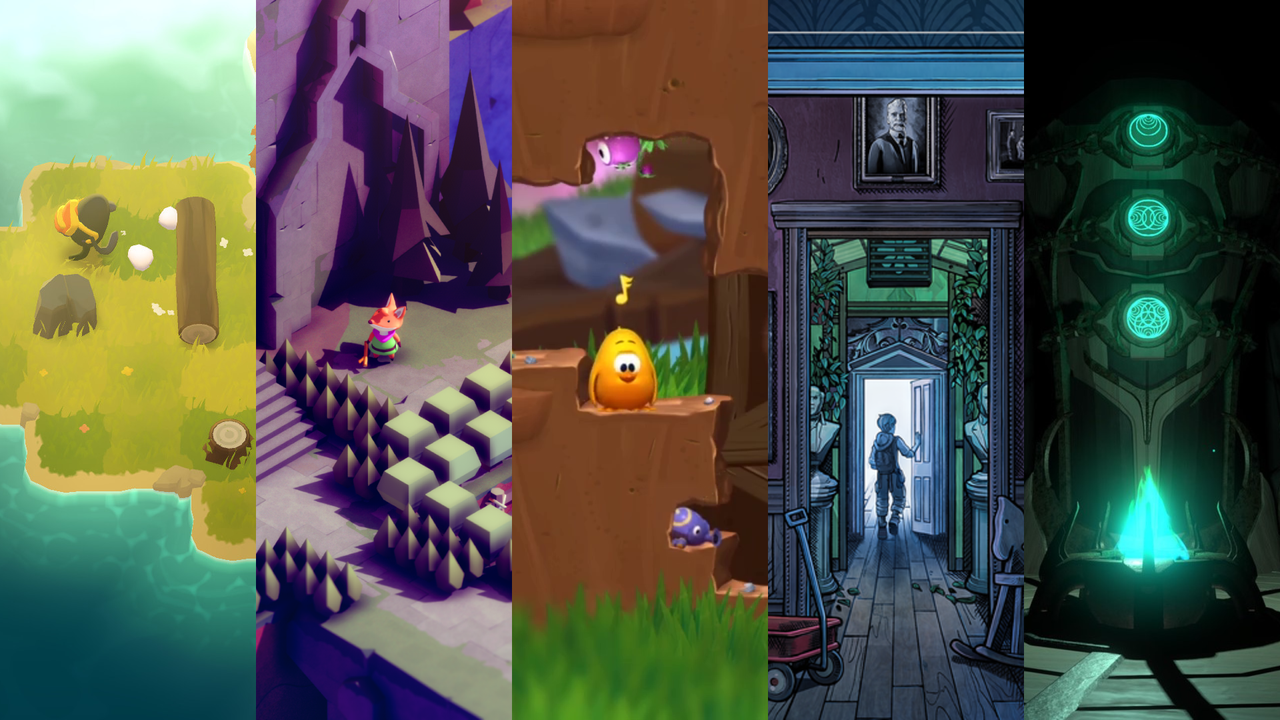

Over the past decade, a new genre has emerged that invariably grabs the attention of any puzzle fan: the metroidbrainia. Many of our favorite thinky games fall under this label — Outer Wilds, Blue Prince, The Witness, Toki Tori 2+, Tunic, and A Monster's Expedition, to name a few — and it has since become one of the most searched genres in our database of thinky games. We even have a dedicated list to the very best metroidbrania games. And while it never feels like there are enough of them, we’re extremely fortunate to have a handful of upcoming metroidbrainias to look forward to, including the likes of Echo Weaver, EMUUROM, and The Button Effect.

After a decade of playing these games, I felt it was time this fascinating concept deserved a deep dive. So let’s take a closer look at what makes a metroidbrainia a metroidbrainia, how different games explore the idea in their own unique way, and then highlight a few wonderful games for you all to explore.

So, what is a metroidbrainia?

Let’s get right to the point: a metroidbrainia game is a non-linear exploration game in which knowledge unlocks further exploration.

For those familiar with its sister genre, metroidvanias, it might be easier to understand this new genre by comparison. While metroidvanias involve upgrading weapons and abilities that you’ll use to open up previously locked paths, a metroidbrainia has you upgrading your mind instead.

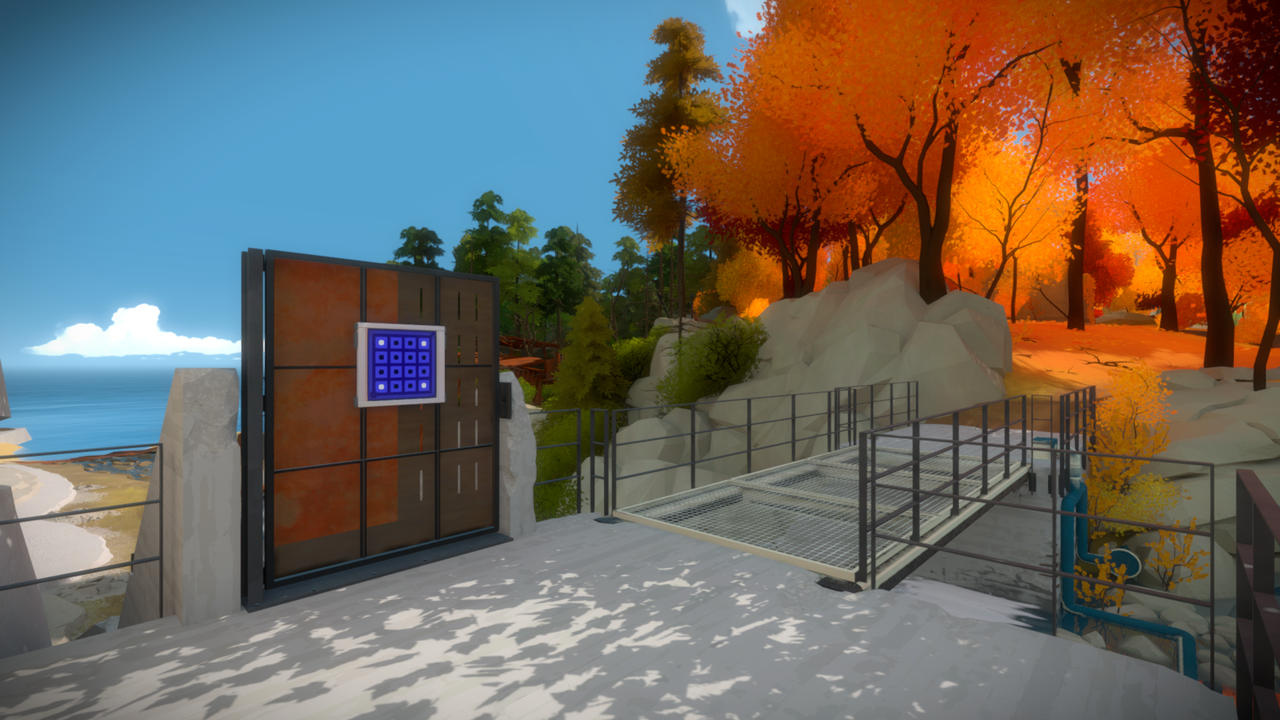

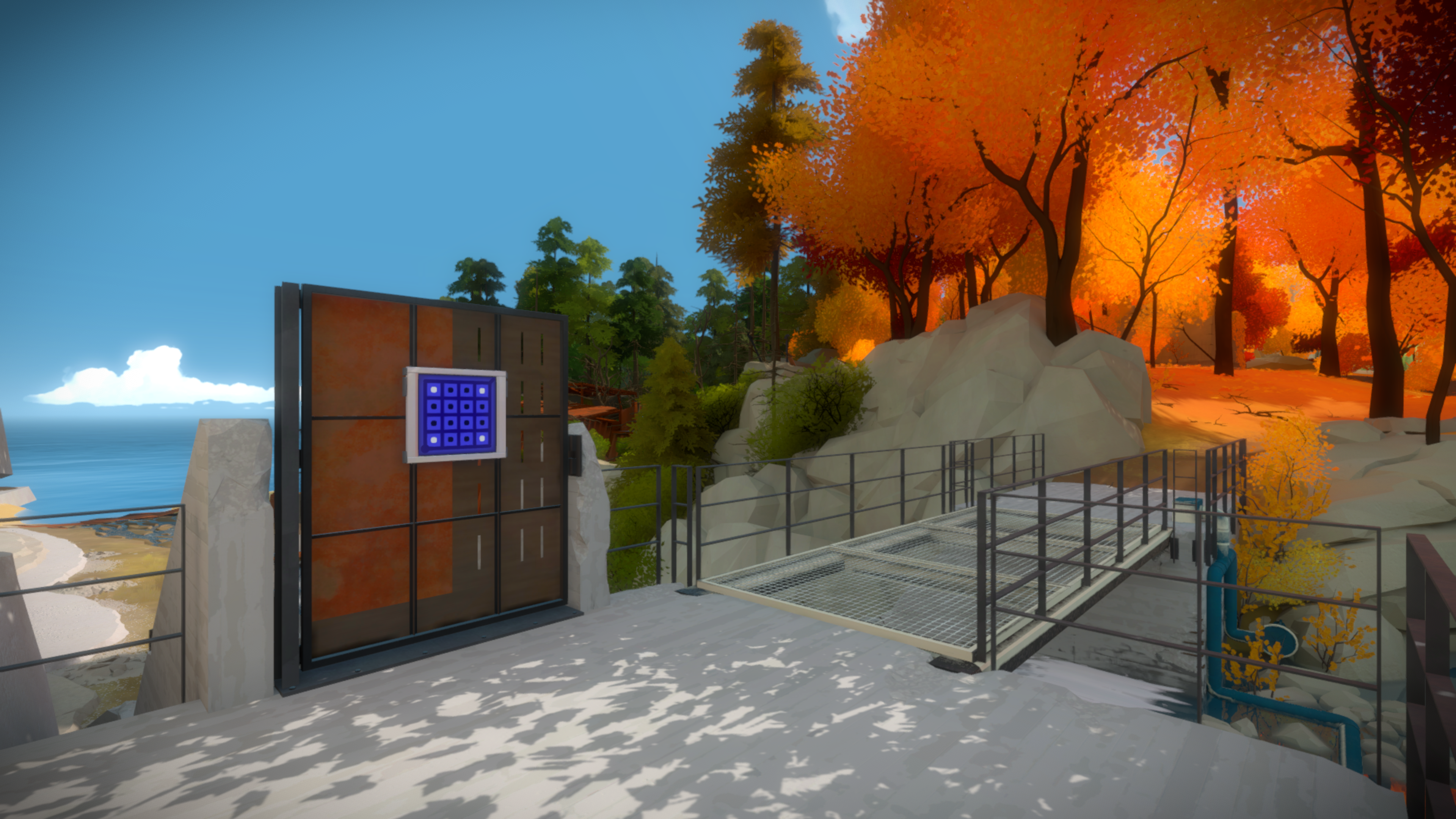

The defining feature of any metroidbrainia game is its knowledge gates: gates that are not unlocked by a physical key or other item in your inventory, but ones that are unlocked with knowledge. As an example, below is a literal gate in The Witness, but this gate has no keyhole, no padlock. You don't blast it open with your super mega missile launcher. Instead, this gate simply asks a question: Do you know the rules to solve this puzzle? If not, come back when you do.

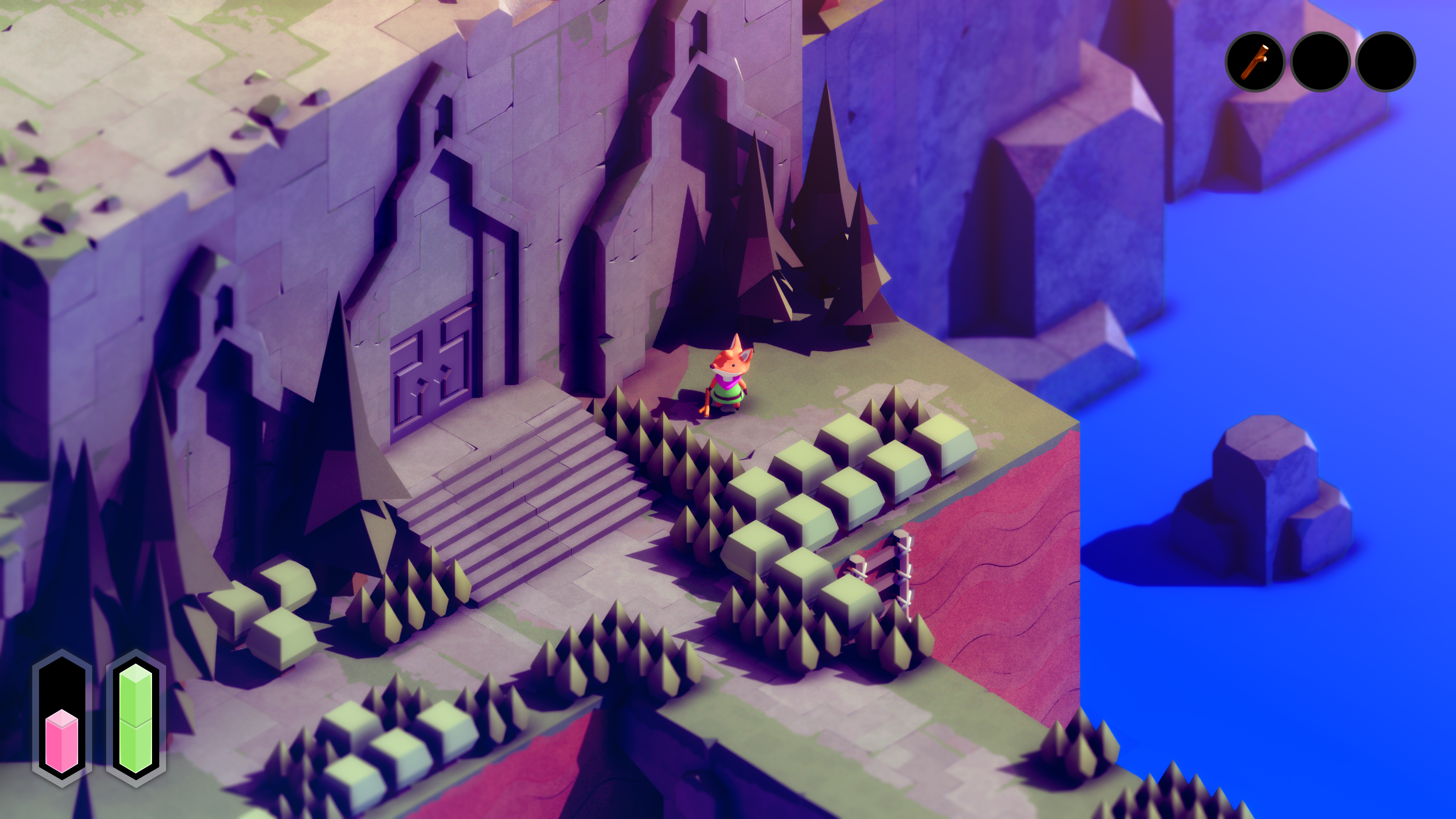

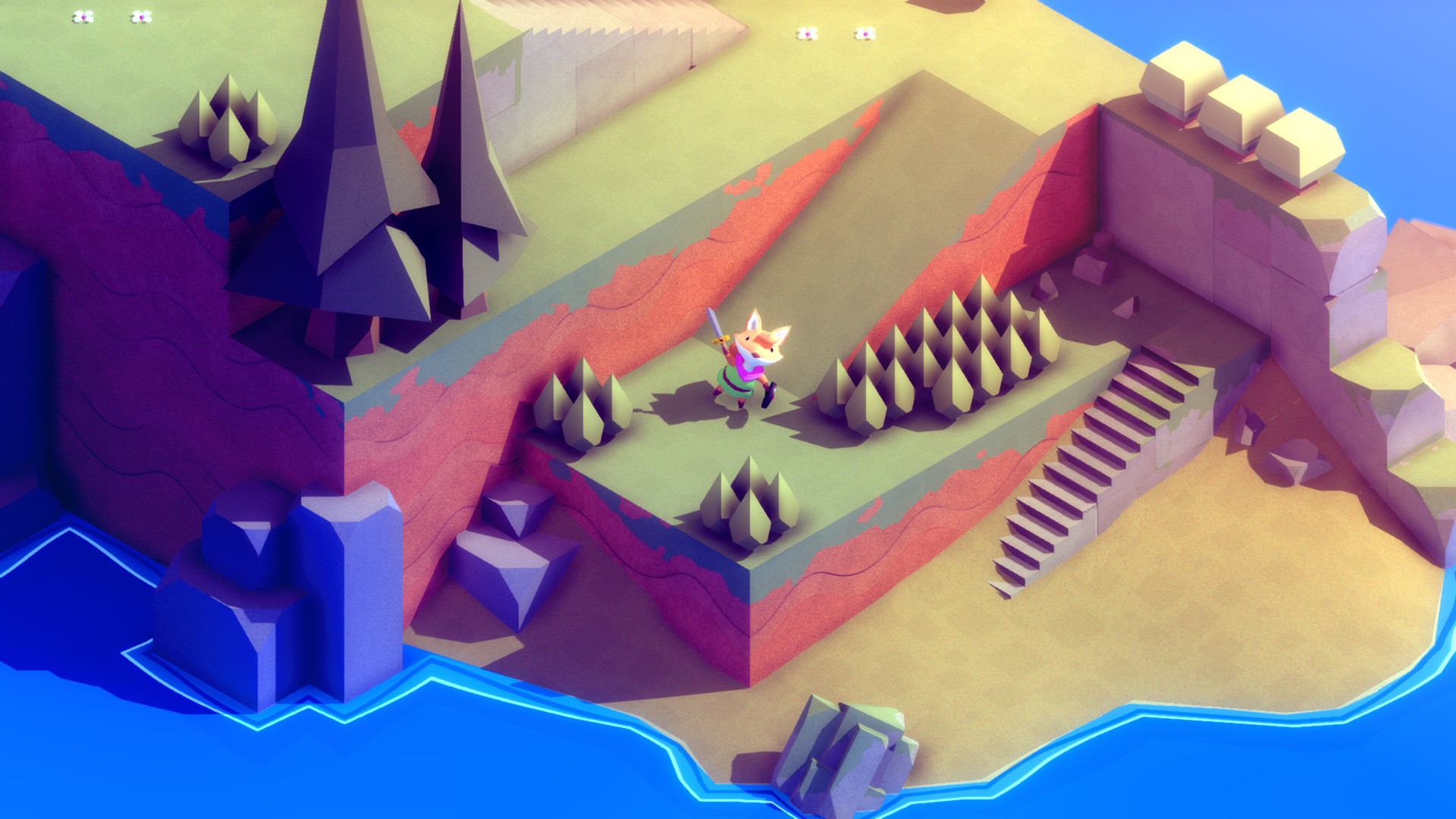

As another example, let's take what I consider to be the quintessential metroidbrainia game: the massively underappreciated Toki Tori 2+. This game may look cute, but it’s a wonderfully clever puzzle game all about discovering how to interact with many curious creatures. In the screenshot below, literally the very first scene of the game, there’s clearly a ledge up there on the left, but it seems completely out of reach. You stomp your little chicken butt and tweet at the bird and frog, but nothing seems to work. How can you get up there? Maybe later you'll know.

No in-game state has to change for either of these knowledge gates to open. There’s no inventory for the game to keep track of the fact that you’ve discovered the key, because the key is in your head. If you play one of these games again and reach the same knowledge gate for a second time, knowing everything you know from your first playthrough, you'll be able to walk right on through.

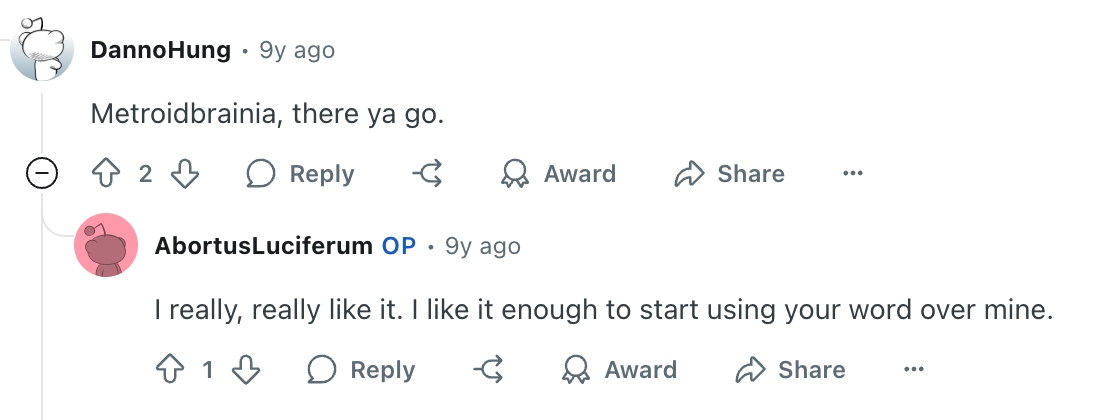

The origin of the term

“Metroidbrainia” is not the only name that's been used for these games, but it has definitely won out. For a while, I mostly heard them being referred to as "metroidvanias-of-knowledge", although that doesn't quite roll off the tongue, does it? I’ve also seen “knowledge-gated games”, which is at least very descriptive.

If we look back at some of the earliest references, we find that in 2016, a Reddit user attempted to coin the term "BrainVania" in relation to games like Fez and The Witness, but it didn't take long for the comments to find the better wordplay:

However, this doesn’t appear to be the earliest use. Back in 2015, on the PlayStation Blogcast, Nick Suttner, writer for Carto and Arranger, used the term “metroidbrainia” to describe the first-person puzzle adventure game The Witness. Like many new words and phrases, it probably originated in multiple places, but one thing's for sure: "Metroidbrainia" seems to be here to stay.

While you decide if you love it or hate it, let’s take a look at some of the key elements of a metroidbrainia in far more detail than anyone asked for: knowledge, knowledge gates, and non-linear exploration.

Knowledge

So, of course, you can’t open a knowledge gate without its key: knowledge. But what exactly does that key look like, and how does the player acquire it?

Systemic and non-systemic knowledge

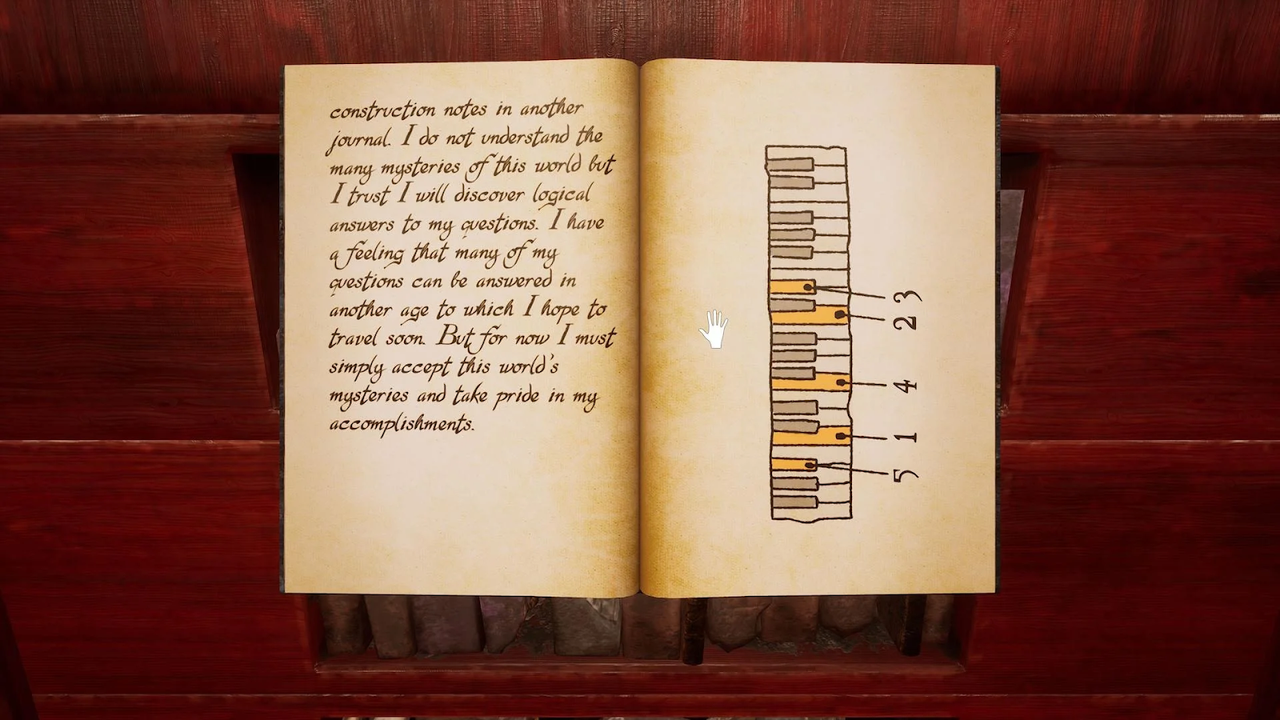

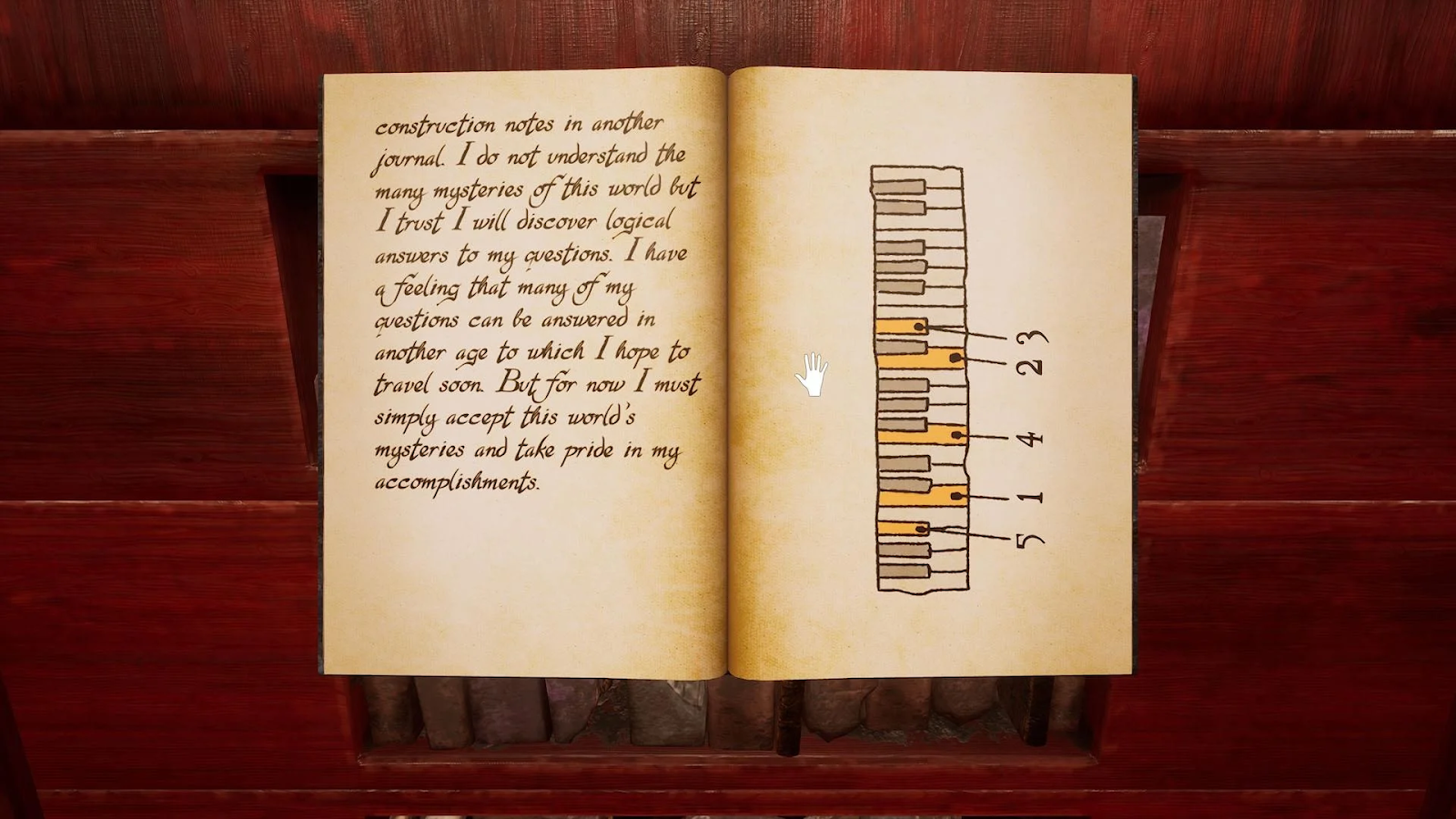

Once I started obsessing over metroidbrainia design, the first thing that became clear was how knowledge could take different forms. For example, we have games like Blue Prince or Myst, where you're often finding self-contained bits of information that might tell you where something is hidden, how to tinker with a device, or a little riddle to apply elsewhere. On the other hand, there are games like Toki Tori 2+ and A Monster's Expedition, where you're learning more about the game’s puzzle systems and rules.

I like to refer to this kind of knowledge as systemic and non-systemic:

- Systemic - Systemic knowledge provides a greater understanding of the game’s systems. These might be the rules of a system, or insights about the consequences of that system (for the mathematically inclined, axioms and lemmas). Systemic knowledge can be applied in more general cases operating under the same system.

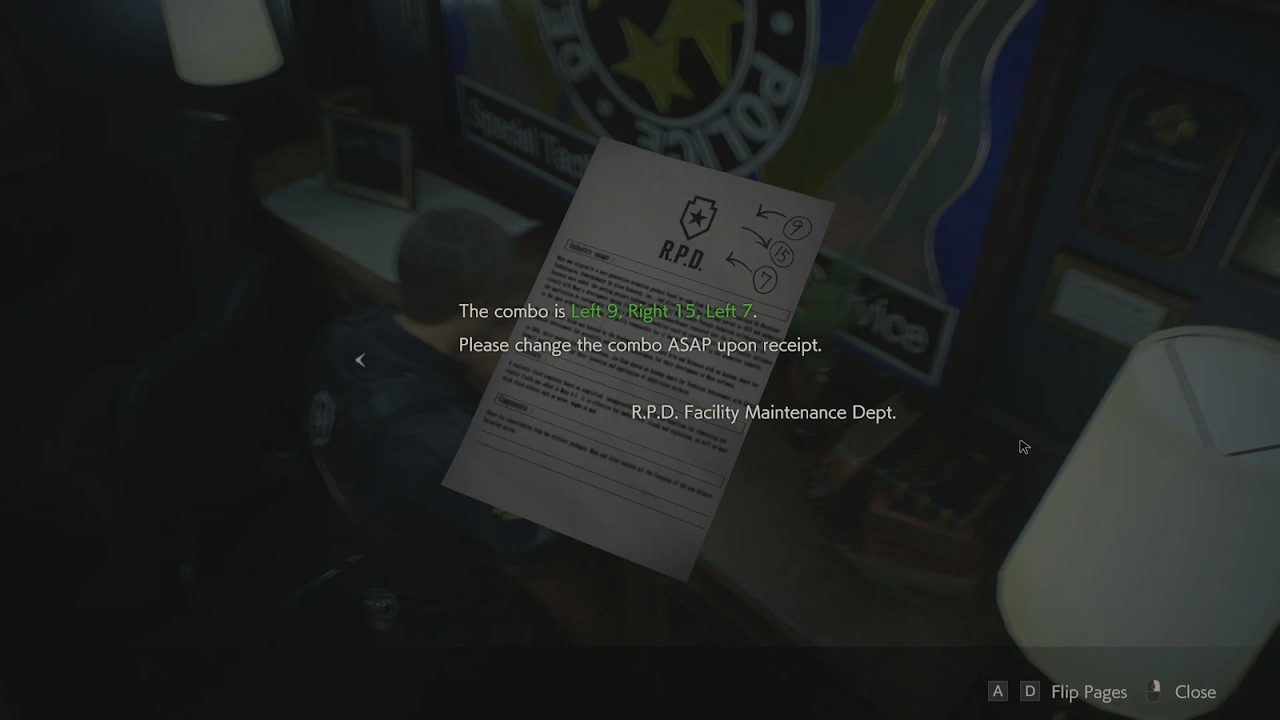

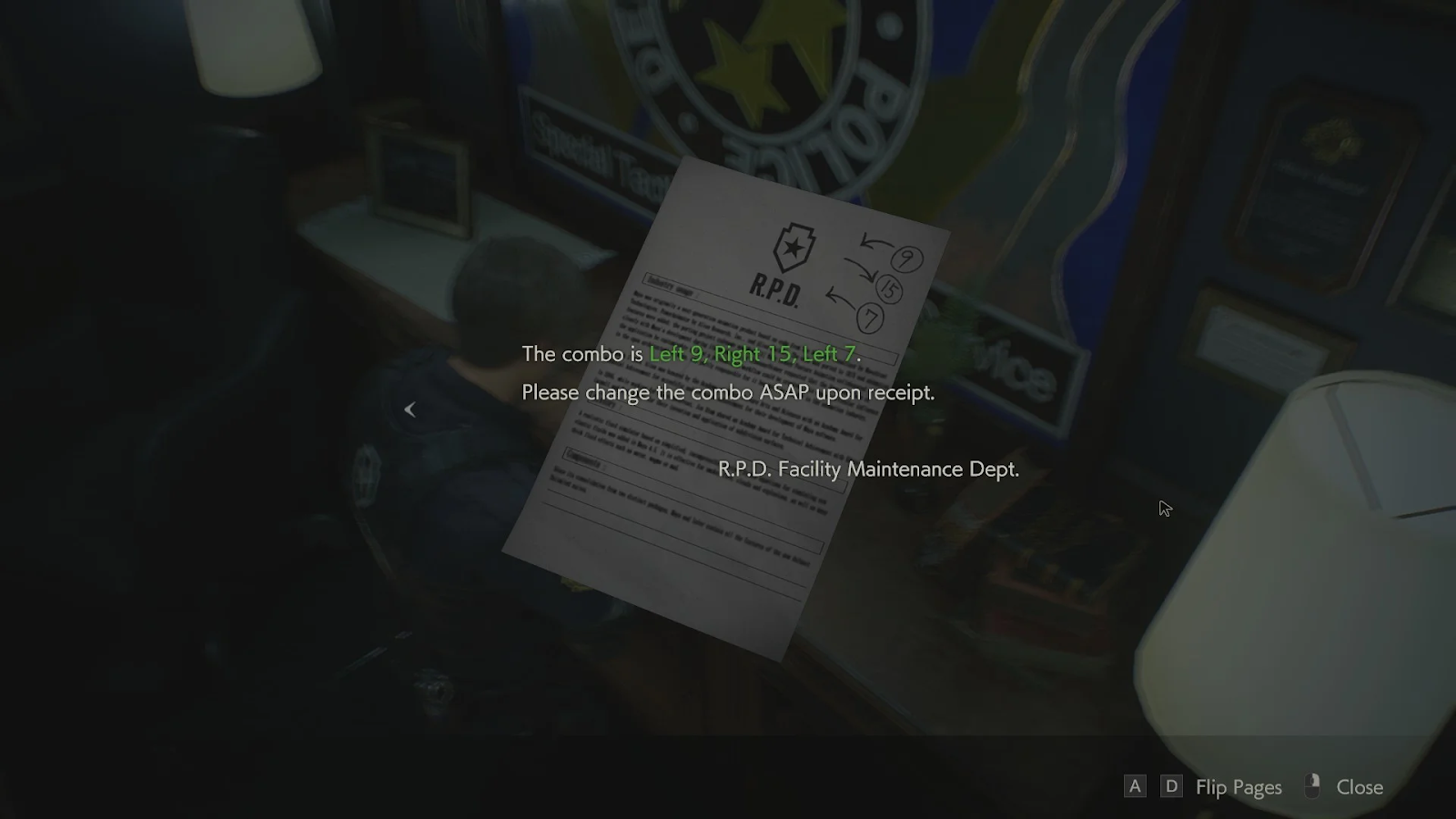

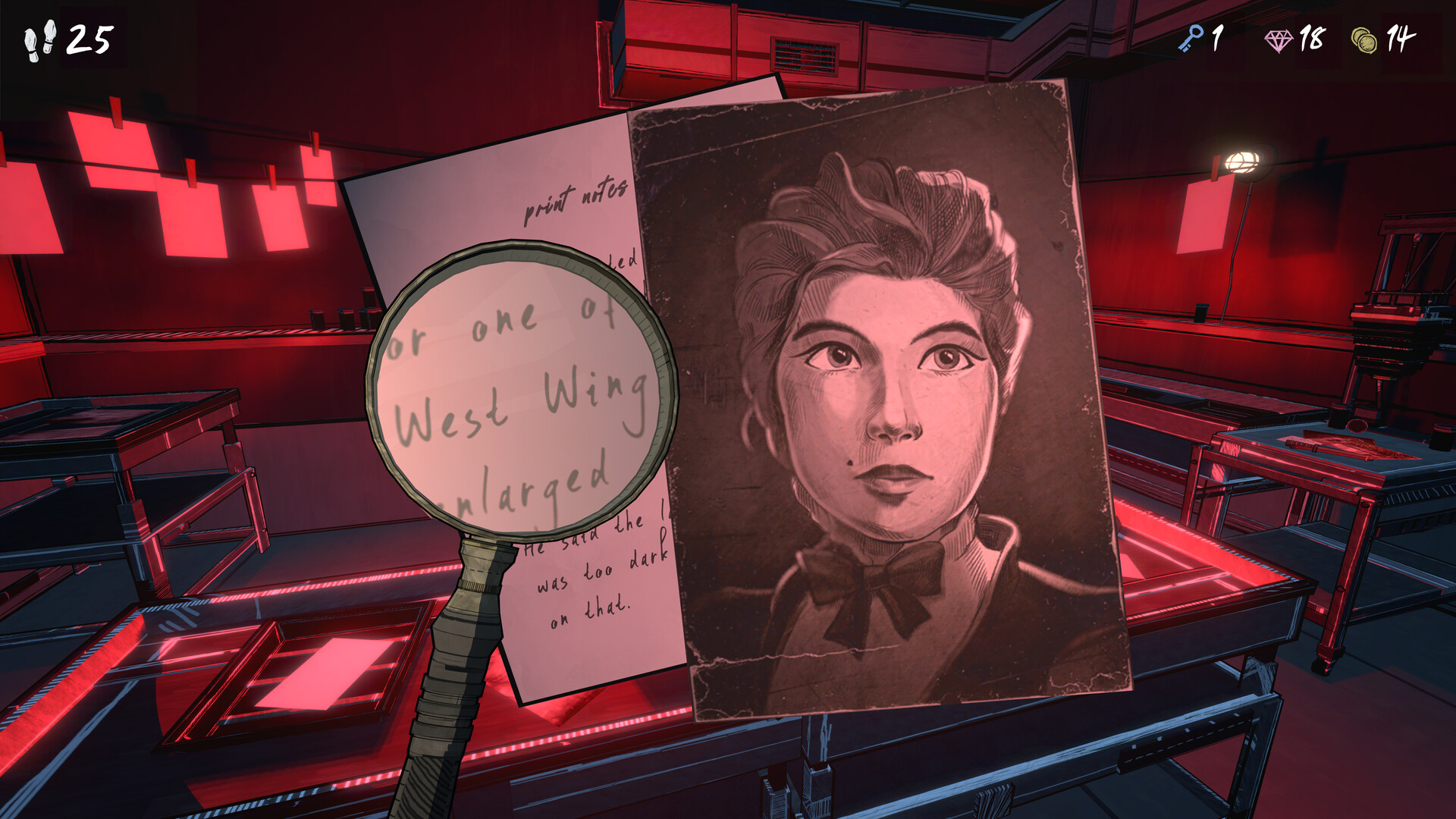

- Non-systemic - Non-systemic knowledge is effectively trivia, with no underlying system to govern why it's the correct information; it just is. Consider escape room-style puzzles like keycodes, sequences, observations like "there are 3 red objects and 2 blue objects", or cryptic clues like "stand beneath the golden spire when the red moon wanes".

Some games also play around with the boundaries between these categories. What might at first appear to be disparate facts may later turn out to be connected through some underlying system. An amazing example of this can be seen in the first-person puzzle adventure, Platonic. This mysterious and abstract world is full of curious codes and contraptions, but what if those codes are not as arbitrary as they first appear?

Of course, non-systemic knowledge gates are found in many other games, well outside of the thinky space. How many games have you played where your path is blocked by a locked door with a keypad? Of course, the code is conveniently scrawled on a note in the next room — such shoddy security practices! Nonetheless, it’s hard to argue that these locked doors are not knowledge gates, even if they're not the most interesting examples.

I find metroidbrainias that deal in systemic knowledge particularly fascinating. It’s not just some random 4-digit code that I never could have guessed, but a fundamental aspect of the game I just hadn’t discovered until now. I can’t just apply the knowledge verbatim, but have to completely recontextualize earlier parts of the game. Those moments are often mind-blowing.

Conveying knowledge through rule-discovery

Another way in which metroidbrainias vary is in how they deliver their knowledge to the player. Of course, there are the more traditional ways, like finding a hidden note or a message scrawled on a wall, or perhaps another puzzle rewards you with the information you need.

The more systemic metroidbrainias, however, often teach their rules and insights directly through the process of puzzle solving. The idea that puzzles themselves can teach the player about their underlying systems - a kind of non-verbal communication - has become a core tenet of modern puzzle design. Rather than dragging players through heavy-handed tutorials, games can teach ideas and concepts by example. Games that really focus on this kind of discovery are known as rule-discovery games.

However, in most rule-discovery games, gaining knowledge in this way would simply allow the player to solve the puzzle at hand. In a metroidbrainia, solving a puzzle in one place could give you the knowledge needed to explore somewhere else entirely.

Your own journey of discovery

Knowledge needn't come from one specific source and may not be discovered in any particular order. While games can attempt to guide you down certain paths of discovery, there is always the possibility of figuring something out earlier than expected, or even brute-forcing your way through a gate and never fully understanding what it asked of you.

However, this property contributes to the sprawling non-linearity that makes these games so fascinating, even more so than traditional metroidvanias. These games can no longer guarantee how and when the player will make progress. It’s entirely determined by what the player understands, and when. In the most extreme case, players might have an important realization as soon as they encounter a gate that requires it, while in other cases, players will be drifting off to sleep when it suddenly dawns on them. There's no single place or time when those epiphanies have to happen.

This also opens up the structure of a metroidbrainia a little more. Rather than direct you to a particular location to pick up a fancy new item, metroidbrainias can gradually nudge you towards the necessary insights. We see a great example of this in Blue Prince, where the game’s randomized structure effectively requires the game to provide multiple ways to arrive at each discovery.

The most beautiful consequence of this non-linear discovery is that each player's journey is truly their own. It's such a delight to share the experience with friends — "When did you realize such and such?", "Woah, you can discover that there?!" — and find all the amazing ways your individual, unique adventures intersected and diverged.

Knowledge gates

So, we’ve covered various aspects of how a metroidbrainia conveys knowledge, but what about where that knowledge is used: the knowledge gates.

Complex input spaces

In a metroidvania (that’s -vania), you can't accidentally blast your way through a super missile door without first obtaining super missiles. It's impossible, since something in the game state has to change: the super missiles need to be in your inventory. In a metroidbrainia, this is no longer true. Knowledge gates need to verify, as best as possible, that the player knows what they’re expected to know.

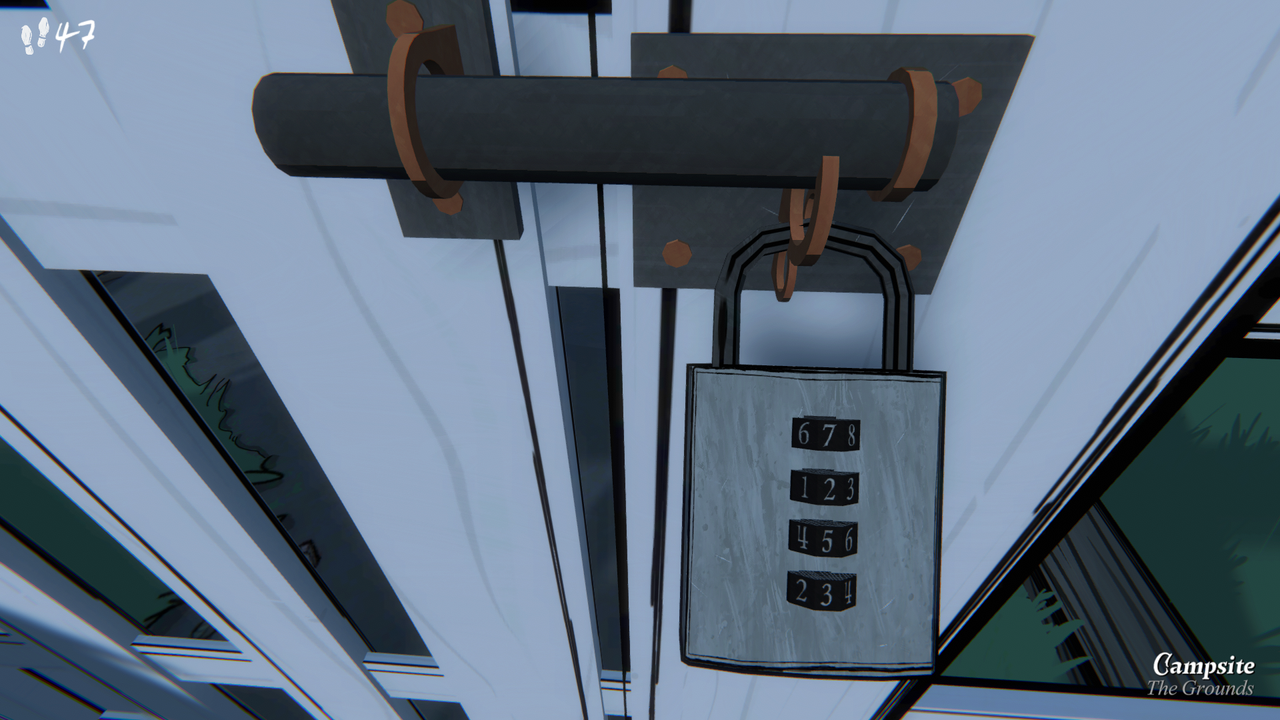

This opens up the possibility that players might guess, stumble, or even brute-force their way through to the other side. This is typically counteracted by making it as unlikely as possible to land on the right answer without the required knowledge. For example, players are unlikely to guess at every possible code or, similarly, they're unlikely to solve a complex puzzle without first understanding the puzzle's rules.

Ultimately, all knowledge gates have to be some kind of complex input space, with perhaps many thousands or millions of things the player could input, but only once they have the required knowledge can they narrow it down to the specific action they must take.

Once I started looking at specific examples, I found that the vast majority of these complex input spaces fit into one of the following four categories, or some combination of them:

- Combination locks - As we’ve seen, a knowledge gate can be as simple as a keypad into which you need to enter a particular code, or perhaps a sequence of levers that must be pulled in a certain order. Animal Well and Toki Tori 2+ both feature musical combination locks, where playing the right sequence of notes will open the way.

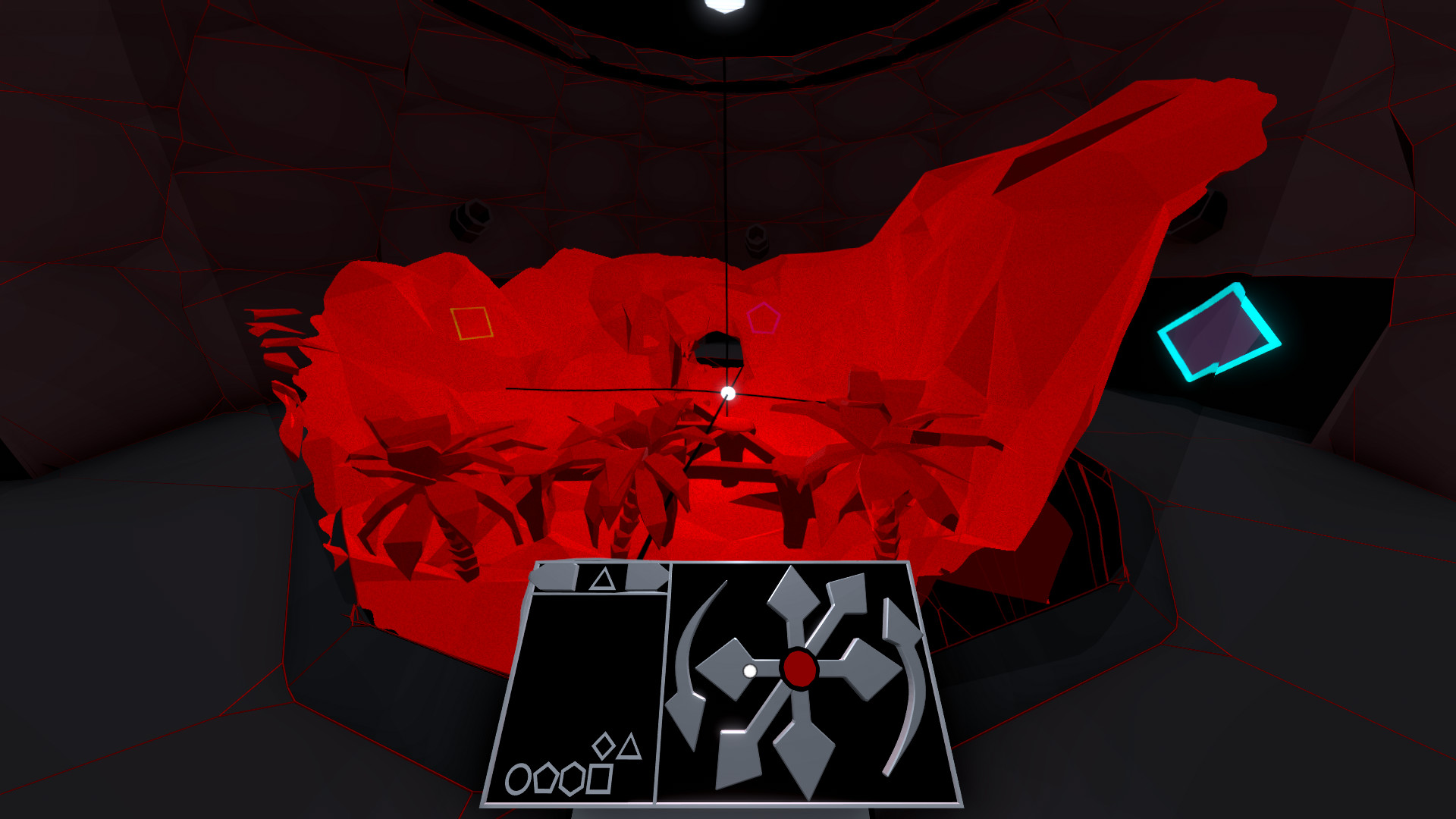

- Interactions - Some knowledge gates require the player to input a specific set of controller inputs or interact with an unexpected game object. We see examples of this in Tunic and Chroma Zero.

- Environmental - Sometimes the key to opening a knowledge gate is setting up the game world in some particular way or waiting for a particular moment in time. There are some excellent examples of this in Outer Wilds and its expansion Echoes of the Eye.

- Puzzles - In the most puzzly of metroidbrainias, they may ask the player to confirm their understanding of a rule or system by applying it to a more general puzzle. This is the main approach taken by Toki Tori 2+ and The Witness.

As we can see, these are all examples of complex input spaces: there are many possible sequences of notes; there are many possible combinations of buttons to press and objects to press them next to; there are many possible ways to configure the environment; and there are many possible paths through a puzzle. It’s up to the player to figure out exactly which option is the correct one.

Knowledge transformation

Many knowledge gates can be thought of as a simple 1-to-1 knowledge check — the knowledge is the input required to open the gate. However, other gates expect the player to transform their knowledge in some way, perhaps combining it with other knowledge, deciphering it in some way, or using it as input to another puzzle.

We see this with all kinds of knowledge gates. Puzzle gates are perhaps the most obvious example, where you’ve got to transform your understanding of the puzzle’s rules into a solution. Take A Monster’s Expedition, for example, where hidden knowledge gates expect you to not only have an advanced understanding of the mechanics, but also identify locations where you can use that understanding to solve puzzles in new ways.

In Outer Wilds, on the other hand, you’ll often need to piece together clues gathered from throughout the solar system, and only when they’re combined will you have the full context needed to open a knowledge gate. Or in Blue Prince, we find hidden clues all over the Mt. Holly estate, but only once you know how to read those clues will you know what purpose they serve.

Mysterious knowledge gates

Of course, we all love a good secret, so why not shroud our knowledge gates in mystery? Some metroidbrainia games are extremely clear when you’ve encountered a gate, whereas others conceal them in fascinating ways.

We can roughly divide knowledge gates into three categories

- Clear - On the less cryptic end of the scale, when you encounter a new kind of puzzle in The Witness or Taiji, you know what’s being asked of you, even if you don't know how to solve it yet. There's nothing unusual or strange, just some rules you haven't learned yet, but you've seen things like this before, and you know roughly how it’s going to work.

- Cryptic - Getting a little more mysterious, some games will present you with something that’s very clearly a gate, but you have no idea what to do with it. For example, in Tunic, you’ll encounter some mysterious metallic doors. Is there a key you need? An item? You know it probably conceals something amazing, but what on earth could it possibly want from you?

- Hidden - Some games, for example Outer Wilds, take this one step further, where the player doesn't even know they've encountered a gate. Rather than an obvious door, puzzle, or cryptic device, the gate is devilishly hidden in plain sight, concealed in some environmental detail, or not even visible at all. When you finally gain that crucial insight, suddenly things you had no reason to pay attention to are recontextualized, and your entire understanding of the game world gets rewritten. Places you thought you had thoroughly explored are now abundant with new things to discover.

The ending was right there the whole time

Some metroidbrainias take this kind of sneakiness to the extreme, hiding the ending of the game right under your nose from the get-go. Of course, most players will have to play the rest of the game to discover it, but nonetheless, the ending was right there the whole time. It's the most audacious of knowledge gates, separating the very beginning of the game from the very end, held shut only by wide-eyed innocence.

An entertaining consequence of games designed this way is that their online forums often feature the occasional "Huh, this is a really short game!" from confused players who have accidentally stumbled through to the ending. Despite this potential pitfall, the incredible realization that everyone else experiences in the intended way is probably worth it.

I’ve often seen this feature described as one of the necessary elements of a metroidbrainia, but I don’t agree with that. It’s cool when a game does it, but there are plenty of metroidbrainias that don’t. It’s just one particularly fascinating way in which knowledge gates can be used.

Non-linear exploration

Now on to the final piece of the metroidbrainia puzzle, the crucial element that connects the genre back to its metroidvania origins: non-linear exploration.

Not just an information game

In a short video by the designer of Tactical Breach Wizards, Tom Francis introduces the concept of an “information game”. Information games, as he describes, are those in which “information is the goal” and “information is what you use to progress.” He later redefined the term to mean a game where “understanding the story is how you progress”. Regardless, “information game” and “metroidbrainia” have been used interchangeably, and it’s easy to see why. That first definition certainly sounds a lot like my definition of a metroidbrainia.

However, I believe there’s an important missing ingredient: non-linear exploration. That is, you apply knowledge in a metroidbrainia as a means to explore its non-linear space. It is precisely this non-linear exploration that connects metroidbrainias to their etymological origin.

Take Return of the Obra Dinn, for example. While it’s one of my favorite games ever — a detective game about determining the causes of death for all 60 crew members aboard a 19th-century trading ship — I wouldn’t describe it as a metroidbrainia. You will be going back and forth between scenes to cross-reference the knowledge you’ve gained, but not for the purposes of exploration. In most cases, using the information you've gathered is just confirmation that your answer is correct. This would be like playing a Metroid game, shooting open a super missile door, and behind the door it just says “Good job, that’s 1 of your 60 objectives complete”.

Abstract exploration

Most metroidbrainias, like Toki Tori 2+ and The Witness, feature a non-linear overworld to explore. You have a physical avatar occupying space in the environment, moving around through rooms and passageways. However, some games often described as metroidbrainias involve a more abstract form of exploration.

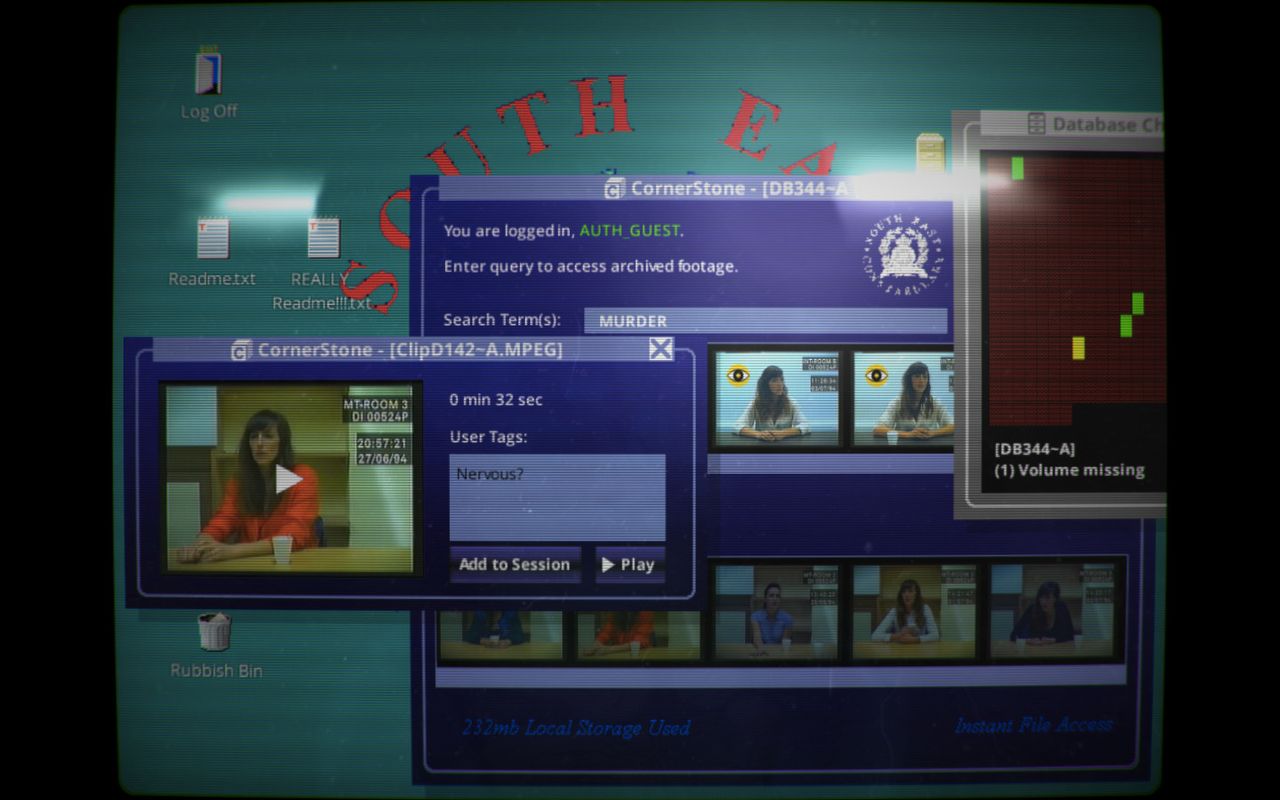

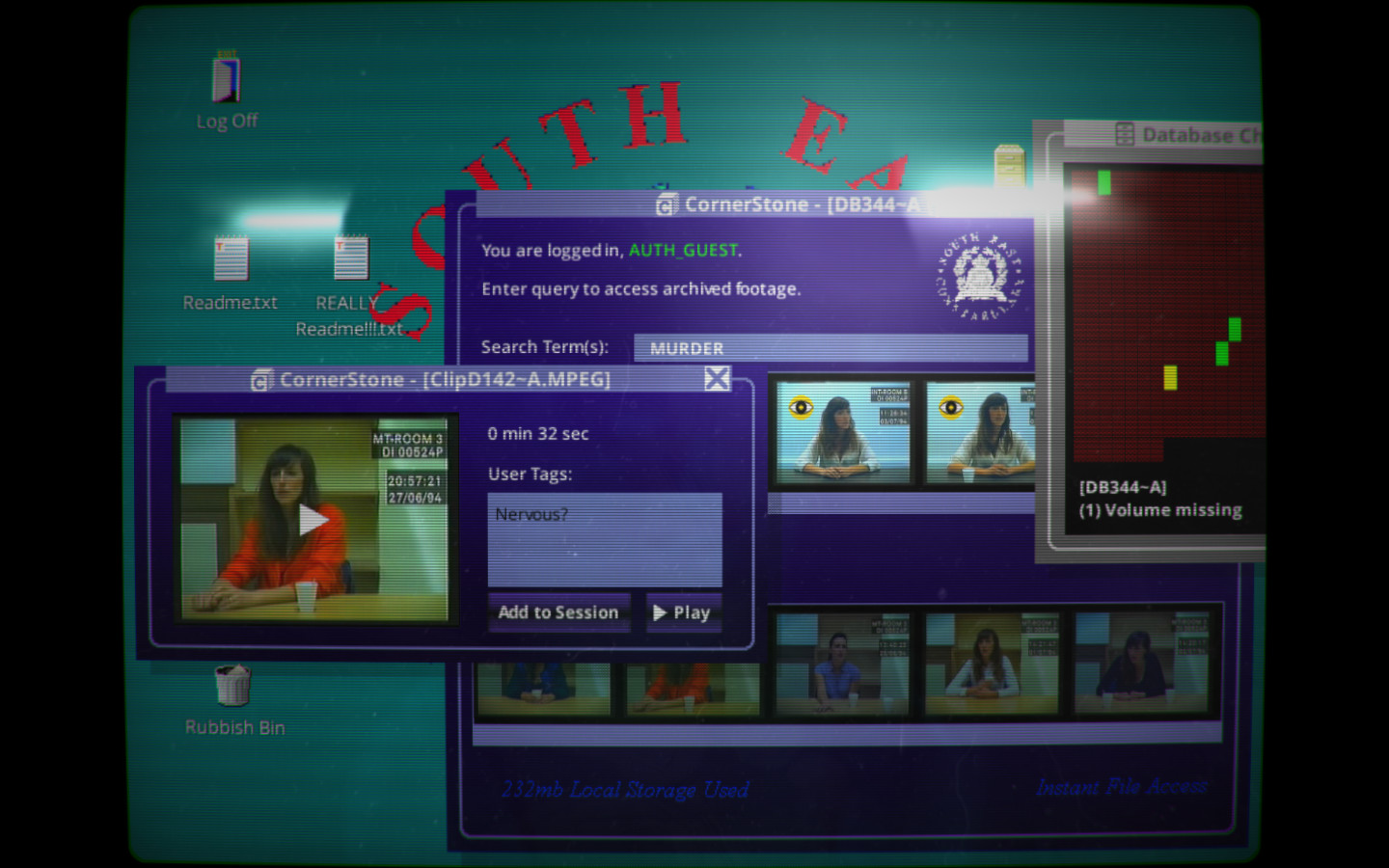

Consider Her Story, in which you search through police interview archives, gathering information to help you unravel the game's central narrative. There’s no character to move, no rooms to explore, yet searching through the interview footage feels like the same kind of non-linear exploratory process as any of the other games mentioned. With new knowledge gained from one piece of footage, you’ll revisit earlier clips with a whole new understanding, allowing you to explore their details more thoroughly.

You might then say, “Ah, but isn’t that just like Return of the Obra Dinn, for which you have refused the adornment of ‘metroidbrainia’?”. However, while Obra Dinn certainly does require the player to go back and forth between different scenes, cross-referencing the information they’ve gathered along the way, doing so doesn’t really open up new paths through the game. In Her Story, on the other hand, you’ll head back to earlier interview footage with a new understanding of what’s important and relevant to focus on, giving you new terms to search for and new interview clips to explore.

Regardless, I personally find myself less inclined to call something a metroidbrainia the more abstract its exploration is, but I don’t think I’d be picky about it. I prefer to treat genres as just a kind of adjective, a shorthand to help you roughly convey certain aspects of a game, and some games may suit a genre more or less than others. So, exactly how well Her Story and Obra Dinn fit the metroidbrainia genre, I’ll let you decide for yourself.

Interwoven worlds

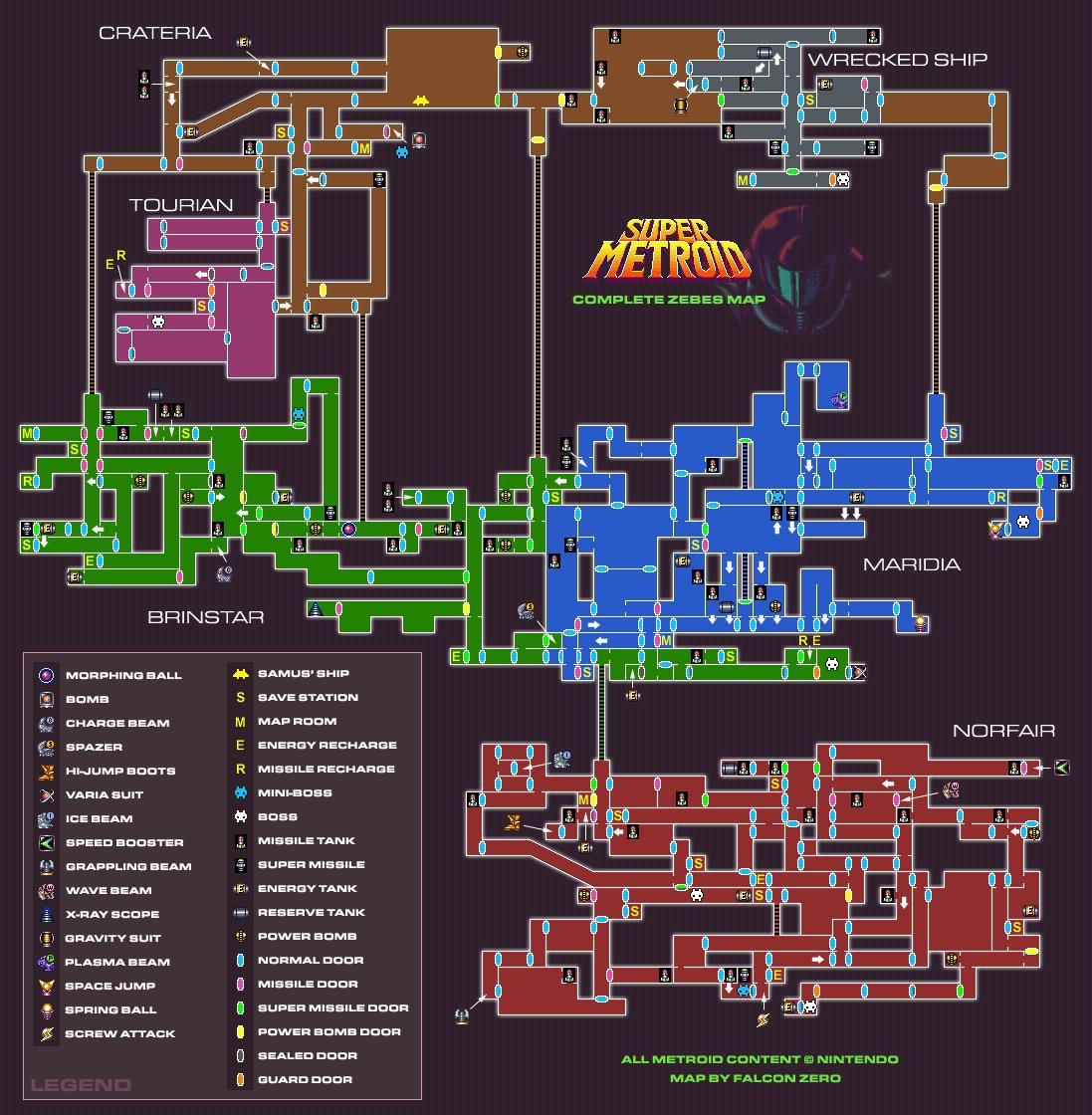

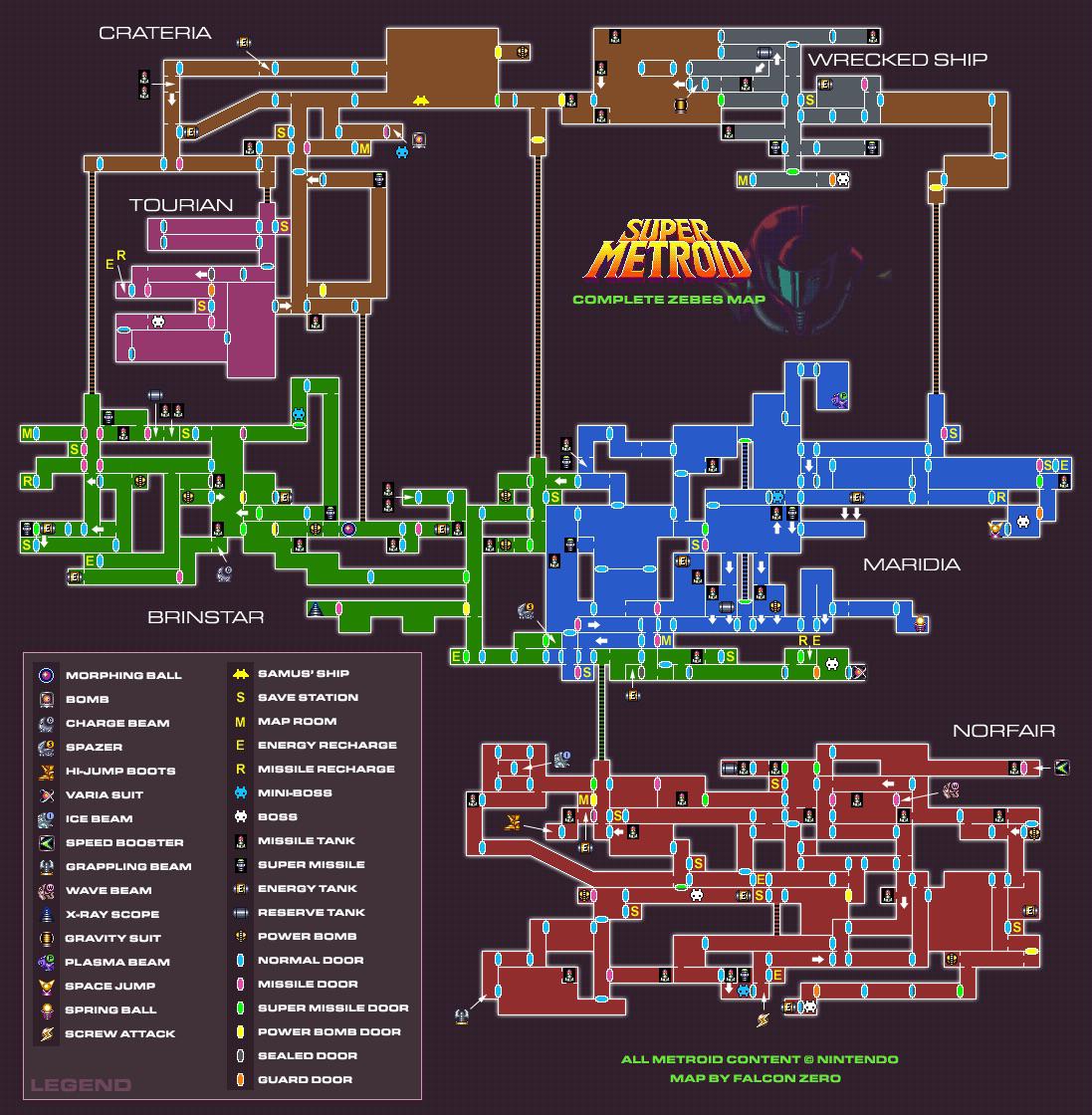

One of the most important aspects of exploration in a metroidbrainia is how complex and non-linear it is. After all, metroidvanias are practically synonymous with sprawling, intricate maps, and so the same should be expected from their new knowledge-based cousins.

Exploring one of these maze-like worlds usually takes you through the following process many times:

- You encounter a gate (which you may or may not know is a gate).

- You later discover the key required to open that gate.

- You head back to the gate to open it with your new key.

- You then explore beyond the gate.

This loop applies to both metroidvanias and metroidbrainias — the only difference is whether the keys are in-game or in-brain.

Of course, you’ll often find yourself in multiple instances of this process at the same time, having encountered multiple gates without gaining the necessary knowledge for any of them. And then, as if things weren’t complex enough, beyond any one of these gates you may discover more knowledge that unlocks other gates you have encountered, creating a tangled web of knowledge-powered exploration.

However, while a metroidbrainia should feature a non-linear space to explore, it doesn’t have to be horrendously complex. In fact, The Witness, despite being perhaps the first game to be described as a metroidbrainia, is ultimately quite simple in its structure.

Metroidbrainia highlights

Our Thinky Games database is a great way to find some of the best metroidbrainias, but I thought I’d highlight a few of my favorites.

Before anyone complains: I know some of these will be stronger examples of metroidbrainias than others, but I do believe they all display metroidbrainia elements in some way. Have a read of my assessment of each game to understand in what ways it does or does not match my core definition of a metroidbrainia.

Toki Tori 2+

There’s a reason I called this the quintessential metroidbrainia, and it even predates The Witness by 3 years. In Toki Tori 2+, you play as a chick with only two abilities, stomp and tweet, exploring a world inhabited by unusual creatures. To progress through the world, you'll interact with these creatures to solve puzzles — perhaps stomping near a creature scares it away from you, while tweeting beckons it closer. It's interactions like these that you'll continue discovering throughout the game, opening up new ways to solve puzzles and paths to explore. Honestly, it's mind-blowing just how many times you’ll say “Woah, I can do that?”.

- Knowledge: Mostly systemic knowledge about how creatures behave, gained through rule-discovery.

- Knowledge gates: Mostly puzzles that are very clear obstacles, some musical combination locks.

- Non-linear exploration: A complex Metroid-style map.

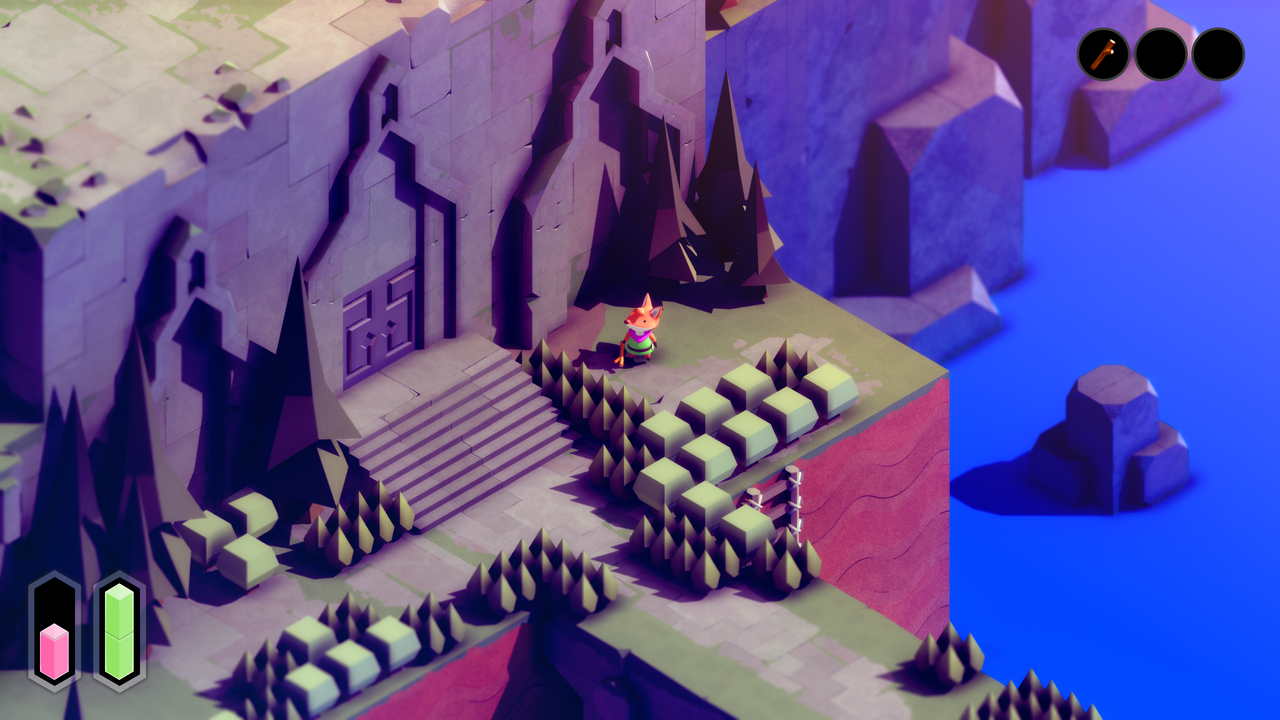

A Monster's Expedition

Another of my favorites, A Monster’s Expedition is an incredible sokoban game about pushing over trees and rolling their logs around to form bridges between islands. There are hundreds of these islands, forming a giant sprawling archipelago of puzzles through which you’ll adventure along a twisting and turning route to your destination.

A Monster’s Expedition features a gentle and mostly linear main path through the game, gradually teaching you the puzzle systems’ surprising depth non-verbally as you go. However, for the most curious of players, there are many hidden branching paths leading to optional secrets, which you’ll only find by applying advanced techniques to earlier puzzles.

- Knowledge: Systemic knowledge about the puzzle mechanics, gained through rule-discovery.

- Knowledge gates: The main puzzles are themselves knowledge gates, allowing you to progress in different directions by solving them with more advanced techniques.

- Non-linear exploration: A very complex and interconnected world to explore, perhaps the most tangled and winding on this list!

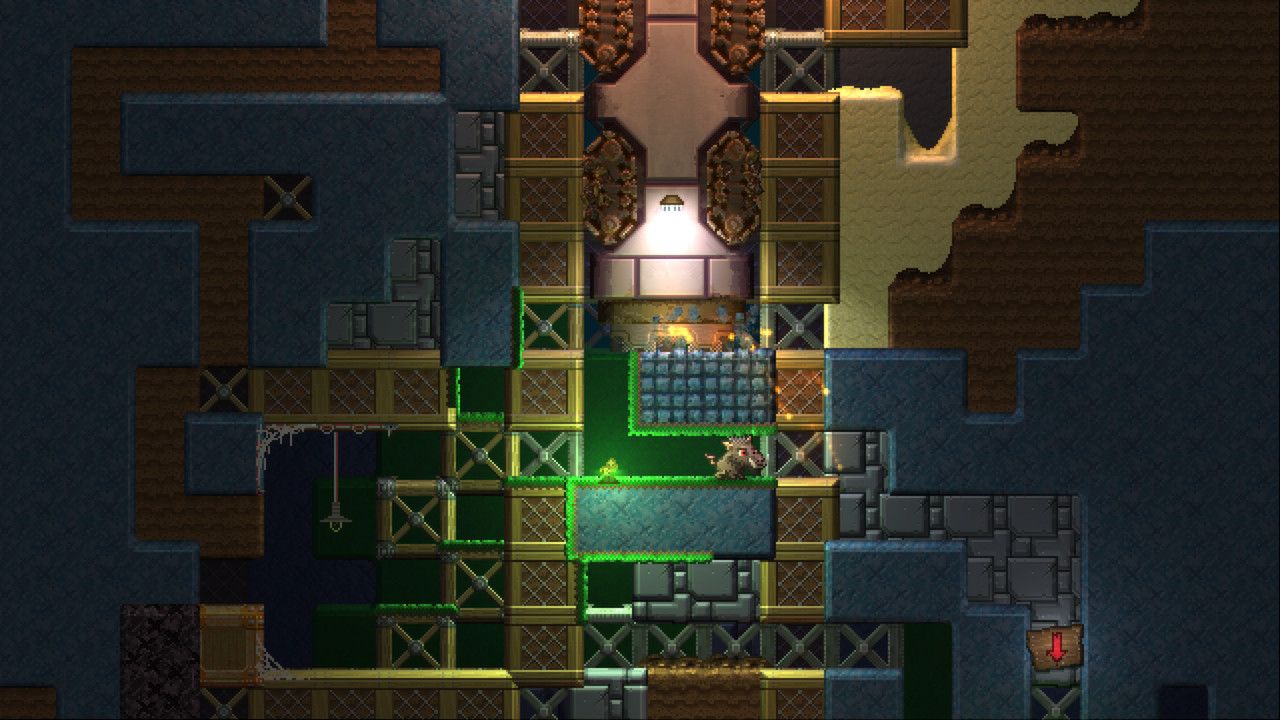

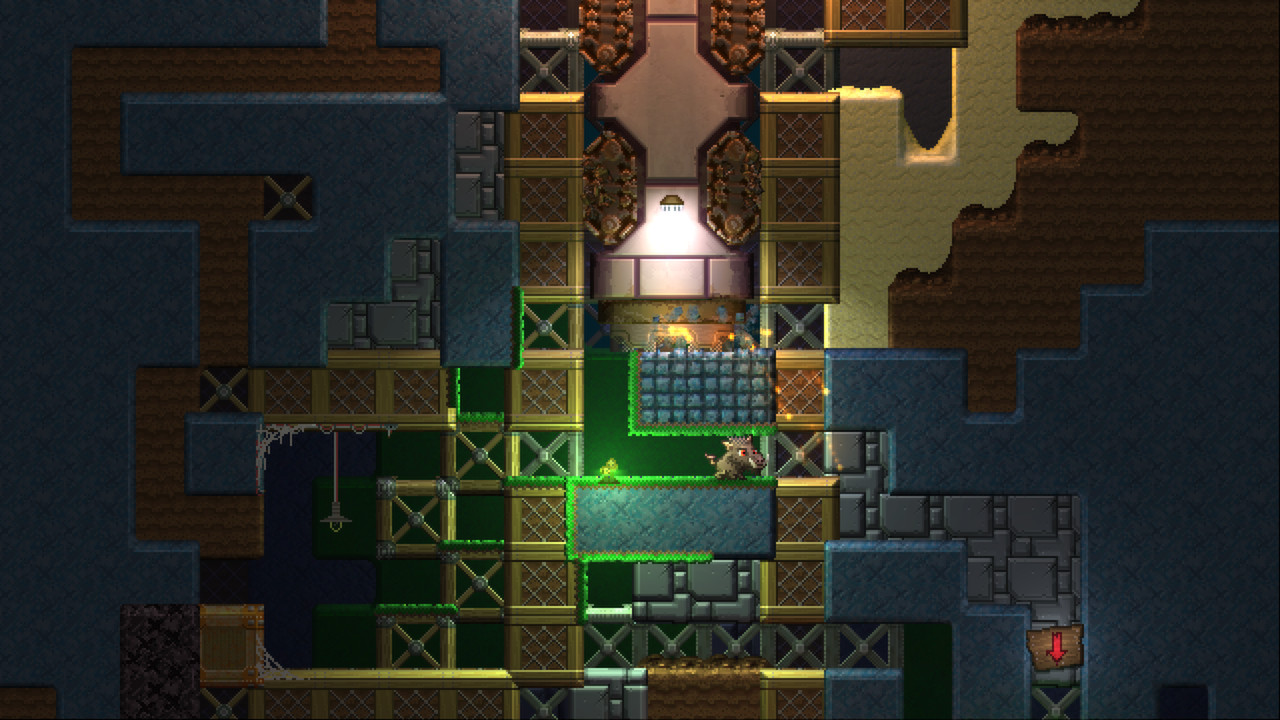

Full Bore

Full Bore is a real hidden gem and is, appropriately, about finding hidden gems in the large and sprawling mines operated by Full Bore Mining Co. The puzzles are what you’d get if you turned Dig Dug into a sokoban game, where the core knowledge you discover along the way is how different blocks behave as you dig and push them around. You will almost certainly pass gems you have no idea how to collect until you later return with an enlightened understanding of the game’s mechanics.

Full Bore’s themes and narrative are unusual and get even more so as you uncover the dark secrets hidden deep within the mines. Matching with this tone, the game also hides some cryptic knowledge gates for the most curious of boars to decipher.

- Knowledge: Systemic knowledge, mostly about how different blocks behave when you interact with them, gained through rule-discovery.

- Knowledge gates: Mainly puzzles that give you access to branching paths, but also some hidden combination lock gates.

- Non-linear exploration: A complex non-linear world to explore, although it also features some traditional upgrade-gated progression.

The Witness

It might have been the first game to be described as a metroidbrainia, but exploring the serene and eerie island of The Witness isn’t quite as complex and interwoven as a Metroid world might be. Nonetheless, the island is full of secret doors that you’ll only be able to open when you’ve learned more about the game’s line-drawing logic puzzle rules. Not only that, but The Witness also features perhaps one of the most dramatic instances of a hidden discovery that completely recontextualizes the game.

- Knowledge: Systemic knowledge about the rules for the game’s logic puzzle symbols, learned through the process of rule-discovery.

- Knowledge gates: Usually literal gates with puzzles on them, which you’ll only be able to solve when you’ve learnt mechanics from the rest of the island.

- Non-linear exploration: Exploration is not as deep and sprawling as we might expect, with the game mostly divided into relatively linear areas, but there’s certainly some non-linearity when it comes to finding secrets.

Sensorium

Sensorium is a first-person puzzler inspired by The Witness, in which you explore zones themed around the five senses — sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell. Yep, there are taste and smell puzzles! Each of these zones has you learning different puzzle types all built on top of a core logic gate system. It’s a fun world to explore, with some secret puzzles hidden throughout.

- Knowledge: A mix of systemic and non-systemic knowledge, with the systemic knowledge learned through rule-discovery.

- Knowledge gates: Slightly cryptic puzzle gates that expect you to apply some knowledge you’ve found elsewhere.

- Non-linear exploration: Just like The Witness, it mostly features sets of linear puzzles, but with a bit of non-linear knowledge-gated exploration scattered around the world.

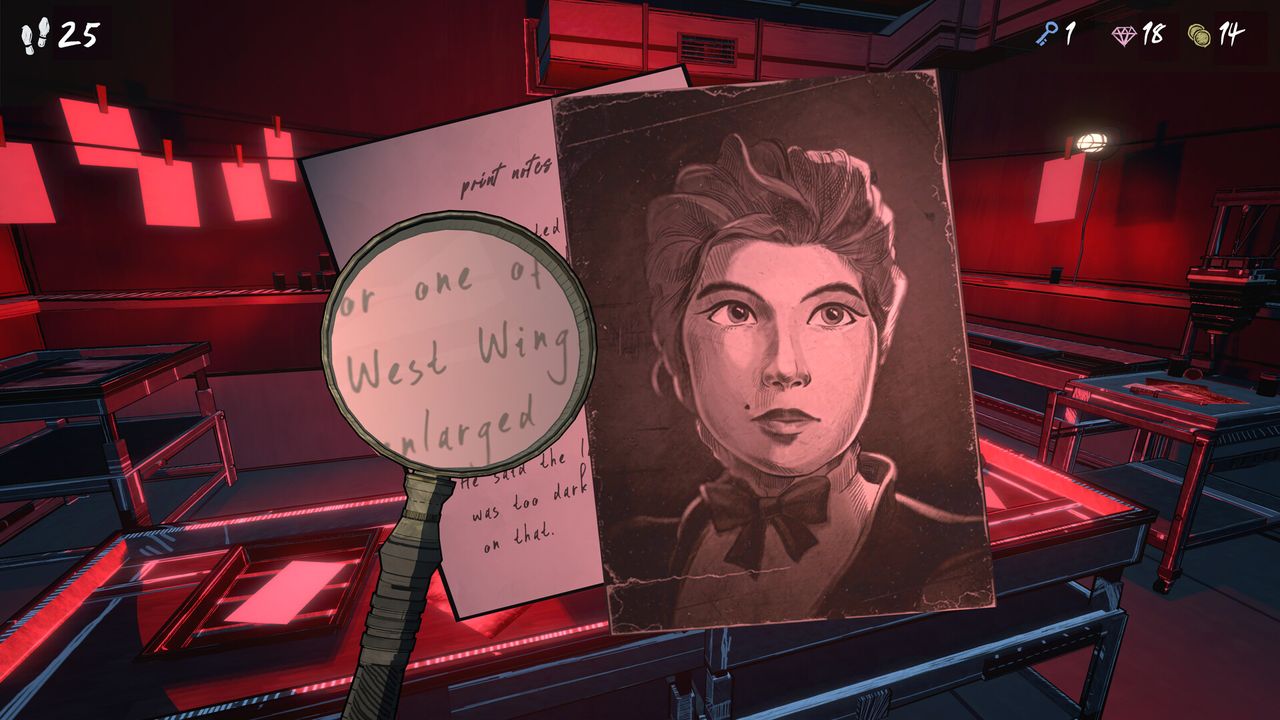

Platonic

Here’s another hidden gem for you, this one following in the footsteps of classic puzzle adventure games like Myst and Riven. In Platonic, you explore an alien world full of strange contraptions and devices, gradually discovering how to use them to open doors and reveal new areas.

Perhaps Platonic’s most notable contribution to the metroidbrainia genre is one of its more complex puzzles, which expects the player to see the bigger picture and wonder whether some of its non-systemic clues might be connected in surprising ways.

- Knowledge: Both systemic and non-systemic knowledge, blurring the lines between the two in fascinating ways.

- Knowledge gates: Mostly cryptic puzzles and combination locks, although even the combination locks are not a simple 1-1 input and require a bit of puzzling out.

- Non-linear exploration: Five fairly linear zones to explore, but with a lot of navigation back and forth between each area.

Outer Wilds: Echoes of the Eye

Outer Wilds is perhaps my favorite game of all time, and while the base game has some great metroidbrainia elements, I particularly want to highlight its DLC. In Echoes of the Eye, you explore a mysterious planet somehow hidden within the solar system and learn of the civilization that lived there and their technology.

As with the base game, much of the genius of Echoes of the Eye is how the knowledge-gating is interwoven with your understanding of the narrative. However, something in particular I love about this DLC is how it subverts some classic puzzle game tropes to create amazing moments of discovery. The most memorable moments are when you exclaim, “Oh my gosh, I could do that this whole time?!” It’s an absolute masterclass in hiding things right under your nose.

- Knowledge: Both systemic and non–systemic, cleverly playing with which kind you might need.

- Knowledge gates: A varied mix of combination locks, hidden interactions, and environmental knowledge gates, some hidden right under your nose.

- Non-linear exploration: A large space to explore, but not particularly complex in structure.

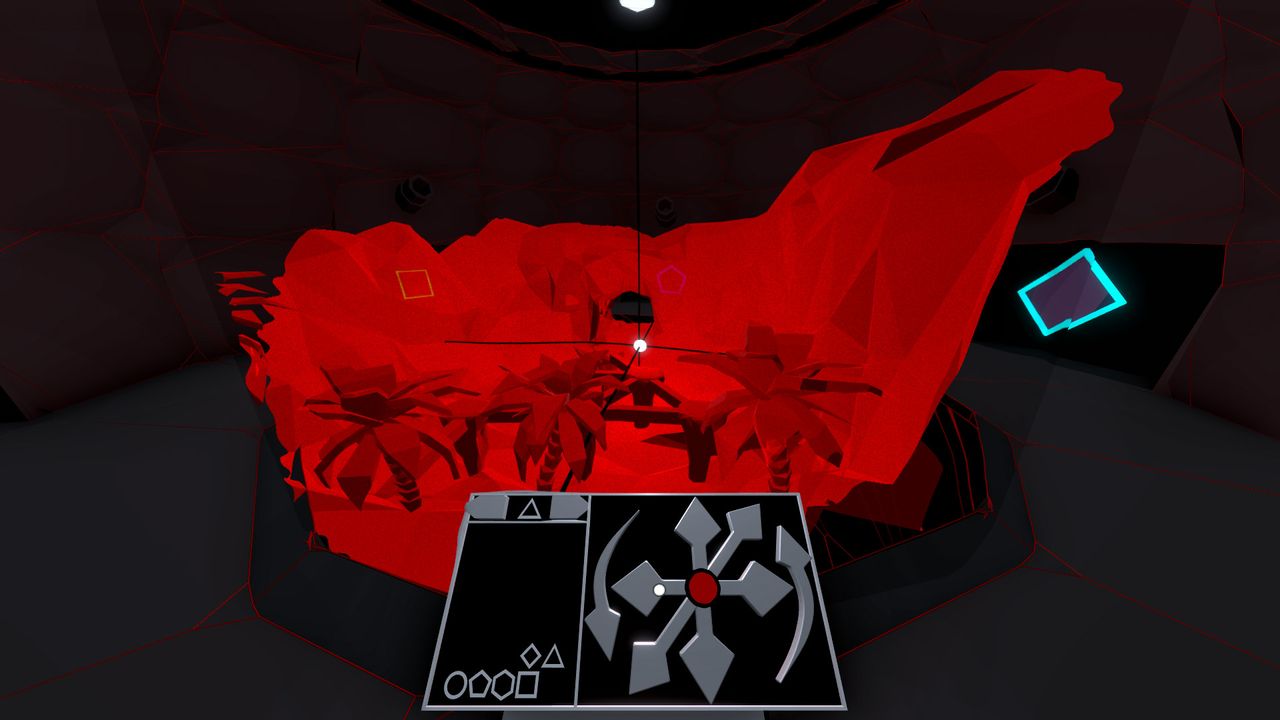

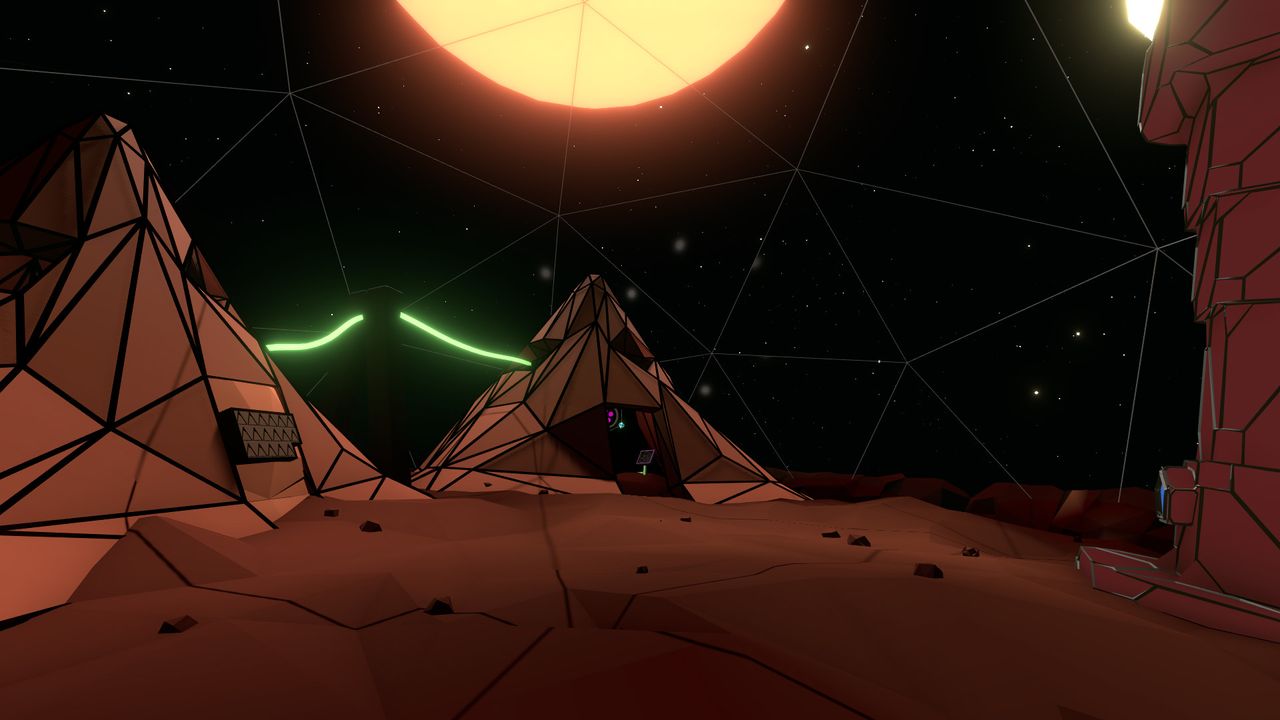

Chroma Zero

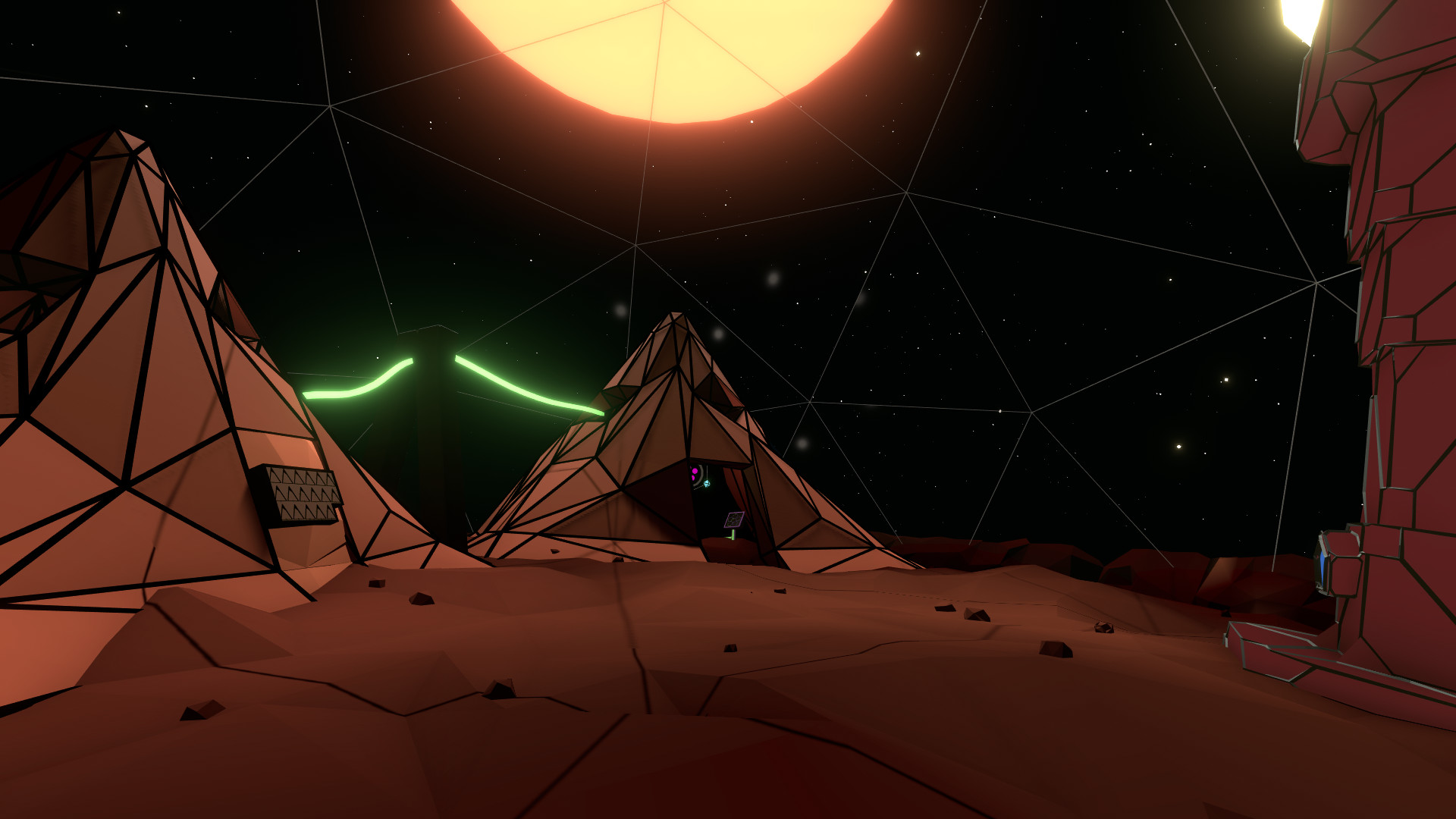

Chroma Zero is not only inspired by Myst and Riven, but also takes huge inspiration from Outer Wilds. In Chroma Zero, you explore a compact and incredibly unusual world of colors and wireframe objects, with the basic ability of being able to add and remove color from objects. As you gain more knowledge about the game’s color-modifying systems and strange contraptions, it feels like you’re dismantling this fragile world, pulling it apart at the seams.

- Knowledge: Some systemic knowledge about the color-modifying mechanics, and also some non-systemic knowledge.

- Knowledge gates: A mix of cryptic puzzles, hidden interactions, and environmental knowledge gates.

- Non-linear exploration: More like one big puzzle box than a Metroid-like world, you’ll have access to most of the physical space of Chroma Zero fairly quickly, but the non-linearity here is more about which puzzles you solve in which order or which concepts you figure out first.

Blue Prince

I’m currently more than 60 hours deep into Blue Prince and still entirely enthralled by its mysteries. The premise is that your puzzle-obsessed uncle has bequeathed you his house, but on one condition: that you find the mysterious room 46.

It’s certainly not a pure metroidbrainia, combining tabletop card-drafting mechanics with puzzle hunt-style enigmas to unravel, but there are plenty of knowledge-gated aspects to the game. One of the most striking aspects of Blue Prince is that it constantly surprises with just how much it opens up, with secret doors, compartments, and clues hidden right under your nose. In many ways, Blue Prince is a love letter to all kinds of puzzle solving, so it’s appropriate that it contains such a variety of metroidbrainia elements.

- Knowledge: Mostly non-systemic, but with some systemic knowledge, in particular related to its drafting mechanics.

- Knowledge gates: They’re all in here — lots of combination locks, puzzles, hidden interactions, and environmental gates, some very visible and some hidden right under your nose.

- Non-linear exploration: The world of Blue Prince is more sprawling than you might expect, with all kinds of secret passages opening the game in mind-blowing ways.

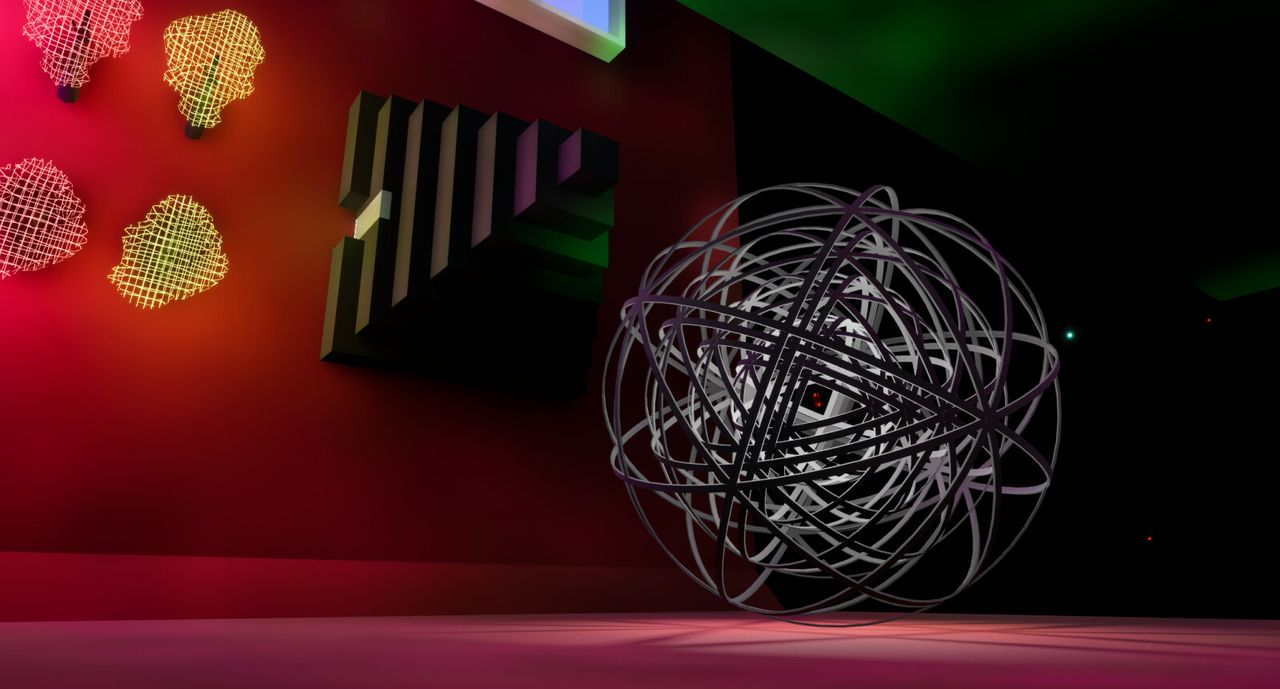

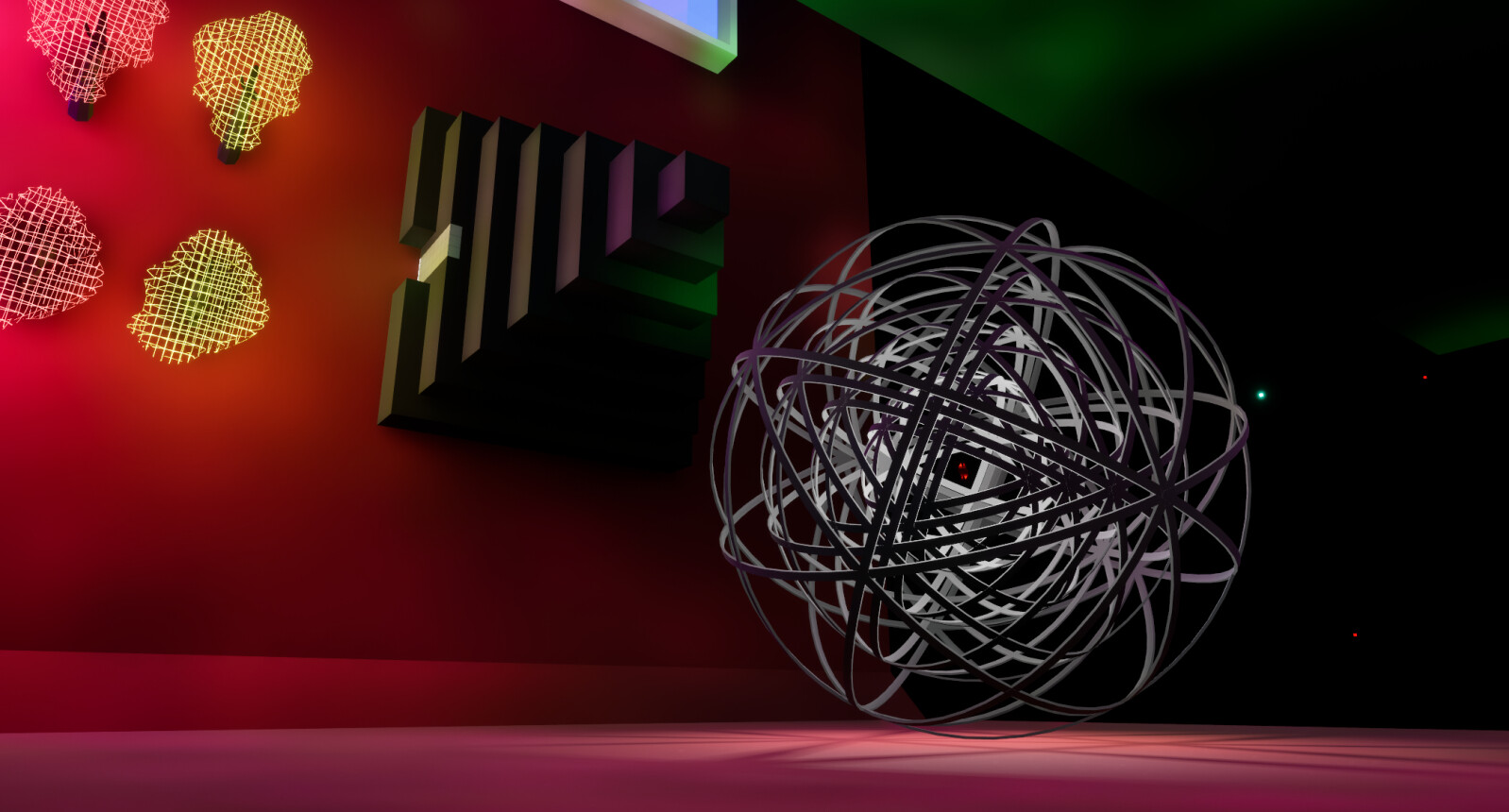

LOCK

If you’ll allow me to get a bit meta for a second (the act of finding great thinky games is a metroidbrainia itself, right?), here’s the knowledge you need to access this incredible game: first you’ll need a PlayStation 4 or 5, then buy the game creation platform Dreams on that PlayStation, and finally search for LOCK. You can thank me later.

Despite being locked away on a platform locked on another platform, the appropriately named LOCK managed to gain a cult following due to its genius puzzle design. The designer wanted to see if he could create a more approachable version of the puzzle hunt experience (of which the most well known is the MIT Mystery Hunt). What he created was a wonderful puzzle box world where almost everything you can see is a puzzle. Fans of Blue Prince would do well to check this out

- Knowledge: Mostly non-systemic codes and instructions, but the knowledge itself is hidden everywhere around you.

- Knowledge gates: Mostly cryptic combination locks, but some hidden interactions too.

- Non-linear exploration: Not a Metroid-like space, so just some simple non-linear exploration, but this world is densely packed with puzzles and secrets.

Tunic

Tunic is a much-loved game in the thinky space, yet hides its deep thinkiness under a surface of action-adventure gameplay. The core game is like a mix of Zelda and Dark Souls, with you adventuring around a non-linear open world and fighting enemies with complex attack patterns. However, throughout the world you’ll find pages torn from the game’s retro-style manual written in a fictional language, which, with a lot of careful analysis, will reveal many deep secrets and will recontextualize the entire environment.

- Knowledge: Both systemic and non-systemic knowledge gained from the in-game manual.

- Knowledge gates: Lots of interaction gates, some cryptic and some entirely hidden.

- Non-linear exploration: Not a pure metroidbrainia, with plenty of upgrade-gated progression too, but certainly a complex world with many secret paths that you will only be able to explore when equipped with the right knowledge.

Leap Year

Leap Year is probably the funniest game in this list, a platformer in which your default jump height is enough to kill you from fall damage. The core of the game is about navigating carefully through rooms, finding paths that let you progress forward without splatting on the floor. You may wonder what makes Leap Year a metroidbrainia — well, there may be more to the fall damage mechanic than meets the eye.

- Knowledge: Systemic knowledge about the game’s core jump mechanic.

- Knowledge gates: Generally platforming puzzles that give you access to new paths, most clearly visible but others a bit more hidden.

- Non-linear exploration: A medium-sized non-linear world map, in which you’ll find yourself criss-crossing through rooms multiple times.

Linelith

Linelith is perhaps the most compact metroidbrainia experience that could just about be called a metroidbrainia. At only an hour long, this tiny game packs some great discoveries. The core of the game is that you’re a little rock creature walking around and solving line-drawing puzzles and discovering the rules of those puzzles in a similar way to The Witness. However, there are more surprises than you might expect.

- Knowledge: Systemic knowledge about the game’s core line-drawing mechanic, gained through rule-discovery.

- Knowledge gates: It would feel a little spoilery to say too much, given how short this game is, but it certainly has some hidden knowledge gates to discover.

- Non-linear exploration: Only a short game, so there’s only so much exploration it can allow, but you’ll definitely want to revisit areas with your newfound knowledge.

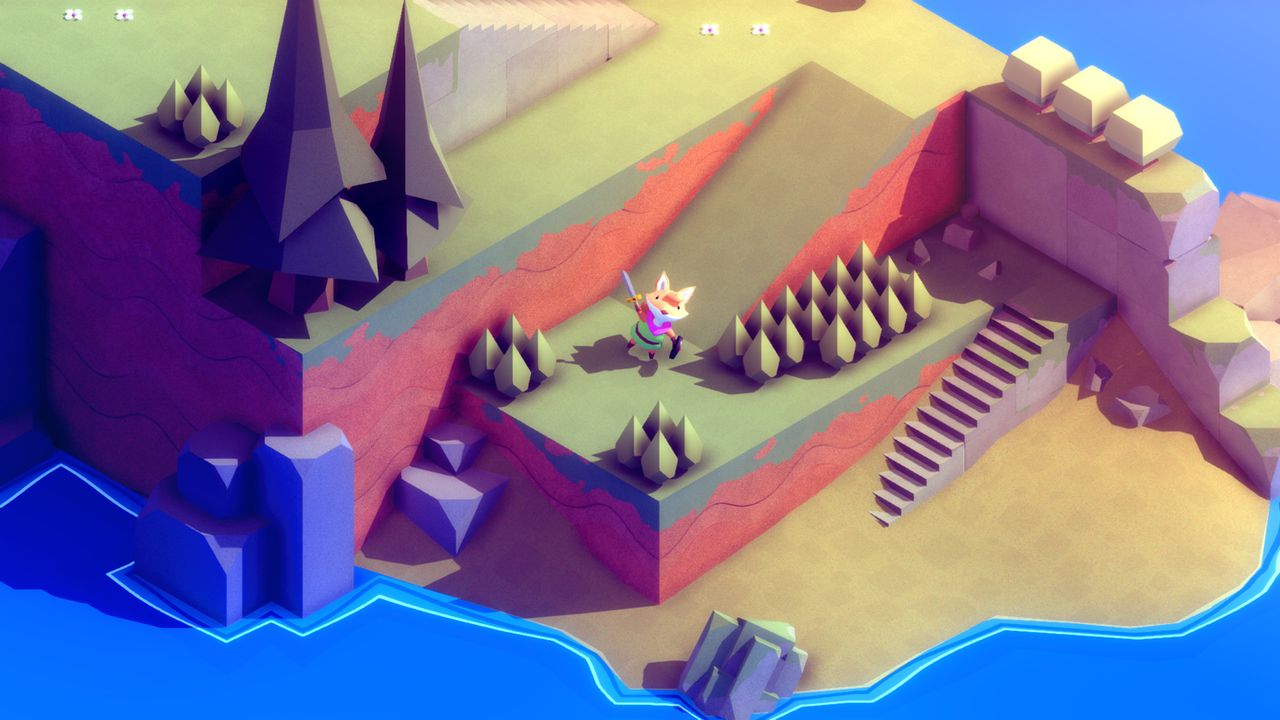

Animal Well

Animal Well won the Community Choice: Game of the Year award in our latest Thinky Awards, and for good reason! In Animal Well, you'll explore a huge, dark, and mysterious world full of strange creatures, with every screen packed full of secret passages and hidden discoveries. While it's not a pure metroidbrainia, as it features plenty of regular upgrade-gated progression, there are also many knowledge-only gates throughout.

- Knowledge: Some systemic knowledge about how the game's various items can be used, alongside non-systemic knowledge like codes and sequences.

- Knowledge gates: The knowledge gates are generally a mix of puzzles and combination locks.

- Non-linear exploration: While Animal Well does feature an archetypal metroidvania-style world, with many branching paths and lots of backtracking, most of that exploration is unlocked via more traditional upgrade-based gates. The knowledge-gated progression typically reveals smaller areas of the game with secret collectables and such.

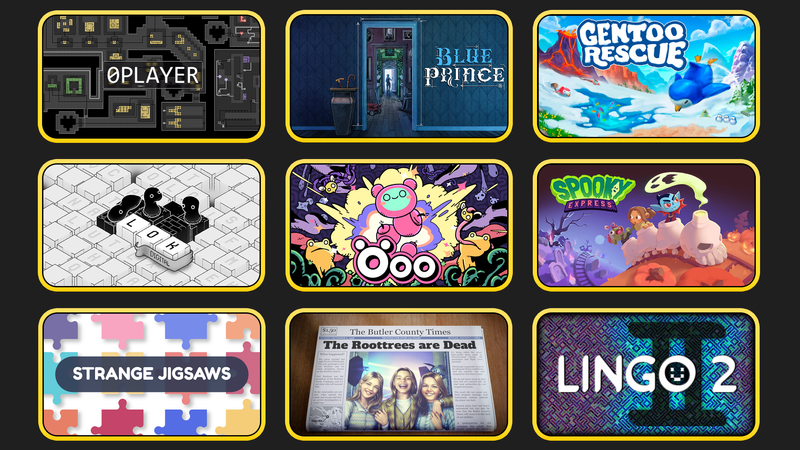

Some additional shout-outs

Of course, there are lots of other wonderful metroidbrainias, but I won’t cover them all in detail. Instead, here are a few more that I quickly want to mention:

- Taiji — Also heavily influenced by The Witness, you can almost think of Taiji as a sequel. It’s 2D rather than 3D, and its puzzles focus on shading in grid cells rather than drawing lines, but its concepts are very similar. Check out my review of Taiji from when it came out. Like The Witness, its non-linearity is relatively minimal and most of its knowledge is acquired via rule-discovery.

- Myst, Riven, and other games by Cyan — In many ways, you can trace the very concept of a metroidbrainia back to these classic puzzle adventure games. They have been hugely influential on thinky games in general, particularly so for metroidbrainias.

- La-Mulana and La-Mulana 2 — The La Mulana games have a serious cult following, and fans of the game espouse its clever (and sometimes very obtuse) riddles. Only one problem: I haven't played it yet! I should sort that out.

- Her Story — Unfortunately, I’m not very well-versed in my Sam Barlow games, which I obviously need to correct at some point soon. However, as we covered, Her Story is a much-loved narrative game about exploring an archive of police interview footage. This creates a kind of abstract metroidbrainia experience, with you backtracking to previous clips with new understandings, gradually piecing together the narrative.

- Void Stranger — This one gained a bit of a cult following when it was released a couple of years ago. On the surface, it’s a retro-style sokoban game, but my understanding is that it hides lots of secret interactions and goes way deeper than you might expect, both with its discoveries and its narrative.

- Lingo and Lingo 2 — I played the very start of Lingo 2 on stream recently, and it was immediately clear why so many people love these games. It’s an amazing combination of cryptic word puzzles and metroidbrainia exploration. I’m definitely keen to get deeper into these games, but I hear they’re also huge and complex!

If it's not obvious to you by now, I'm deeply obsessed with this genre. To me, metroidbrainia games offer the perfect combination of my favorite things: puzzles, exploration, secrets, and mind-expanding discoveries. They are games steeped in mystery, carefully constructed webs of mystery to unravel, with some of the most jaw-dropping moments of any games I've ever played.

My hope is that talking and celebrating these games might inspire others to explore this space, both as players and designers. Yes, I just want more metroidbrainias to play!