If you could wipe your memory of a game to play it again for the first time, which game would it be? Puzzle games often top the list because those “aha” moments we crave are inherently single-use — you don’t get to have the same realization twice. For many, the answer to this hypothetical is The Witness, a game that in many ways is about those moments. Now, 6 years later, Matthew VanDevander’s Taiji might just give us the opportunity to relive that experience.

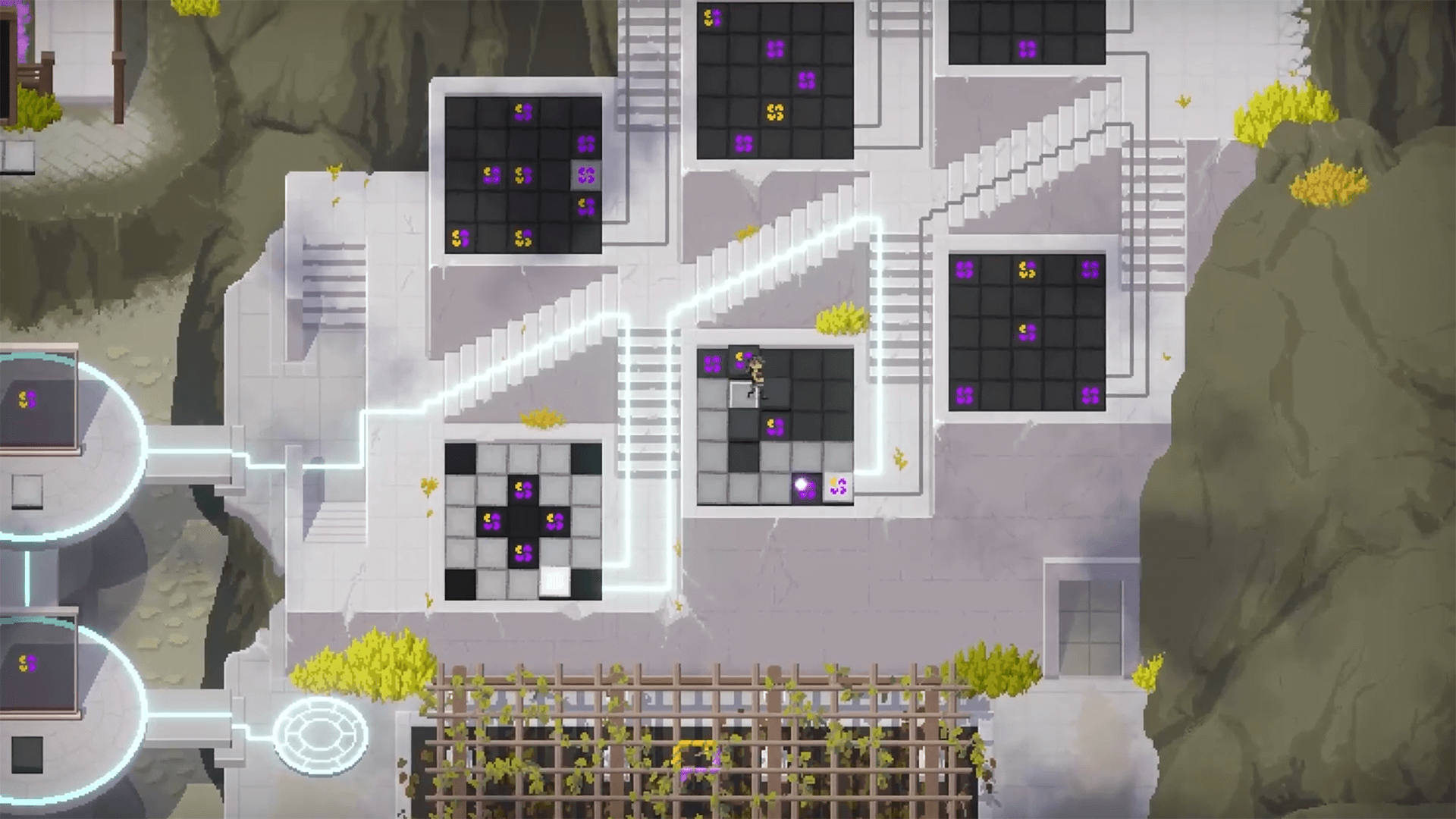

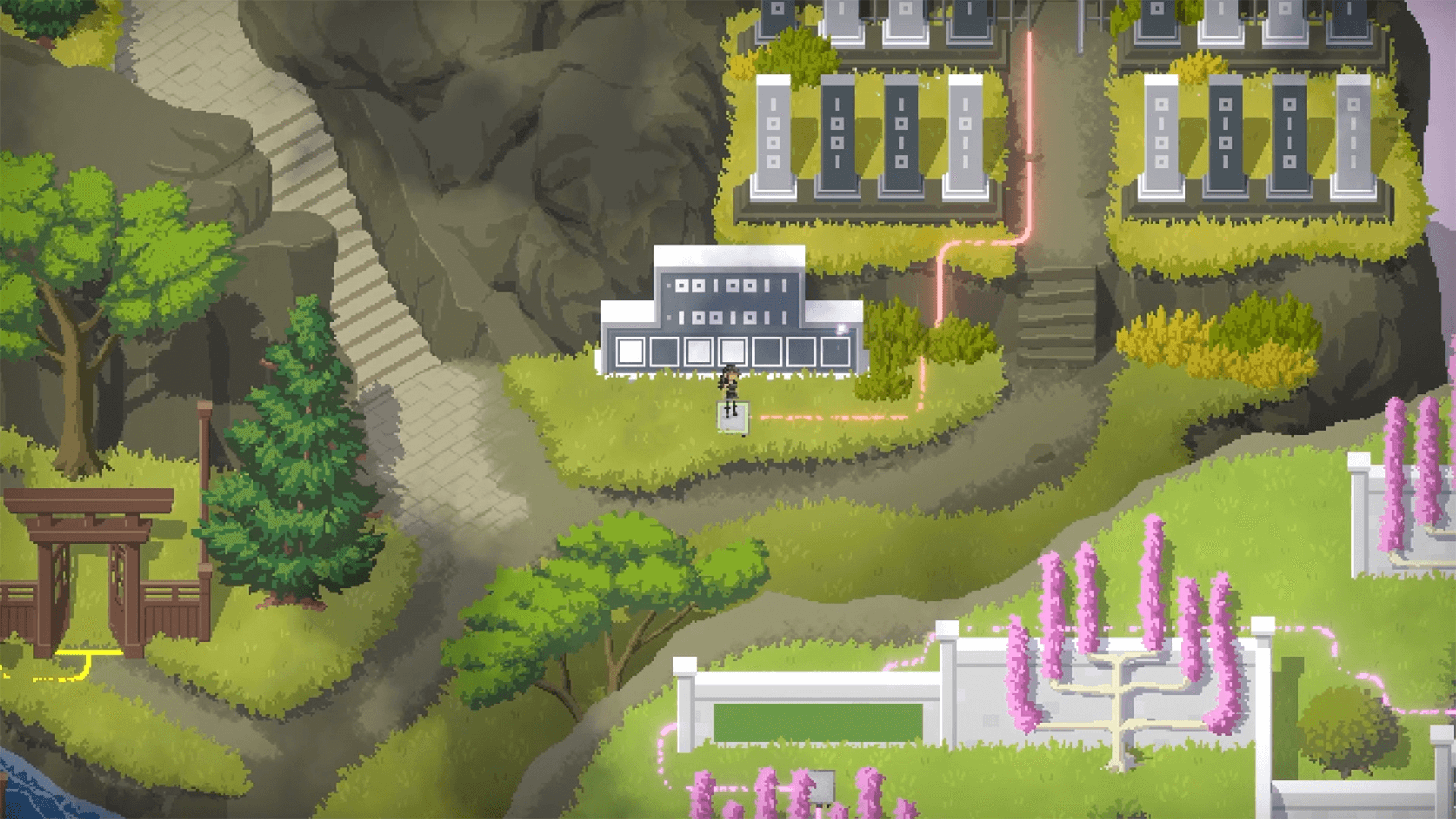

Like its predecessor, Taiji takes place on a mysterious, serene island filled with both logical and observation-based puzzle panels. This time, however, the island floats among the clouds, the puzzle panels take a different form of input, and we view the world from a 2D top-down perspective. Immediately, it is both familiar and unknown at the same time — a whole new, exciting world to explore.

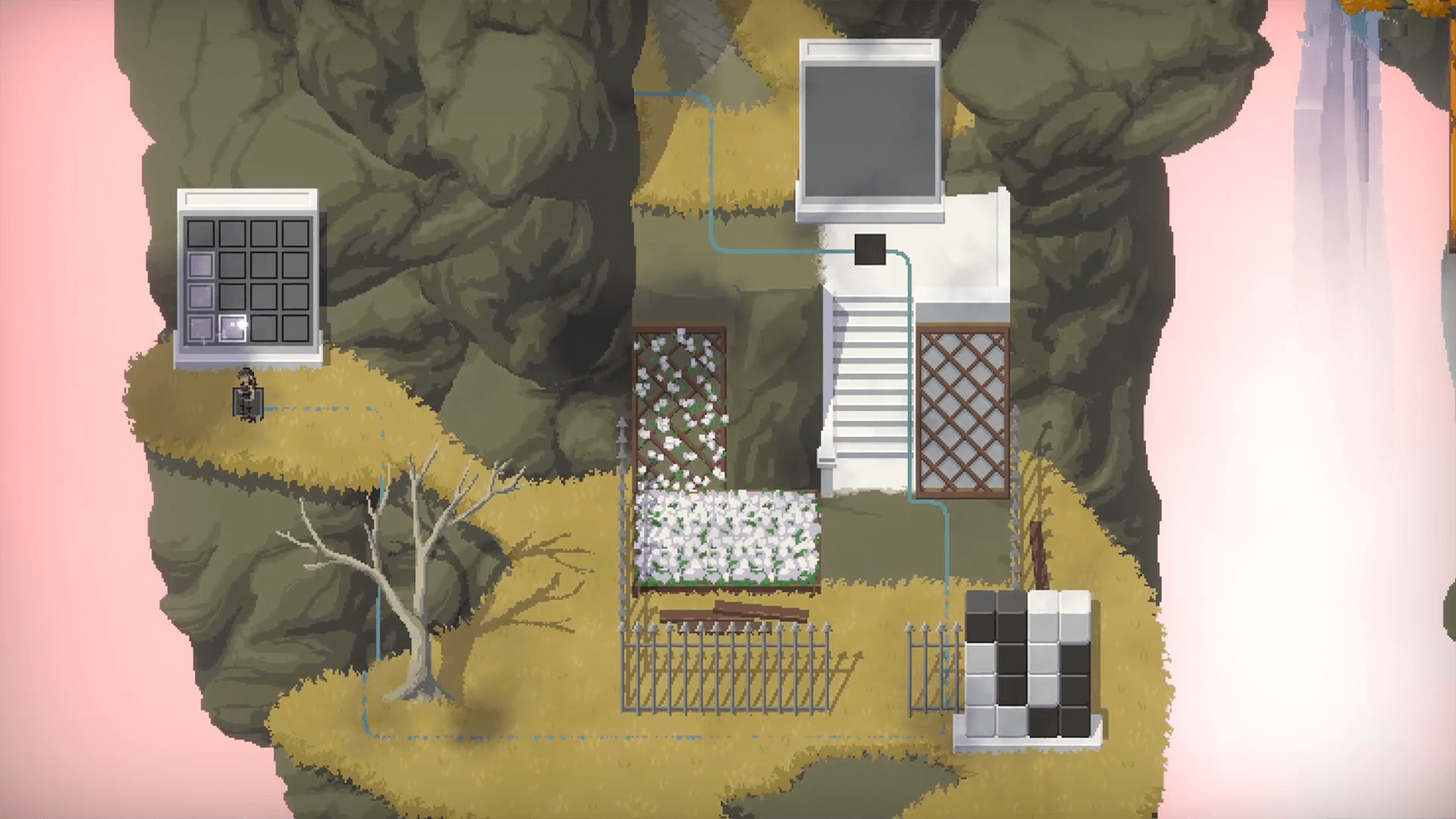

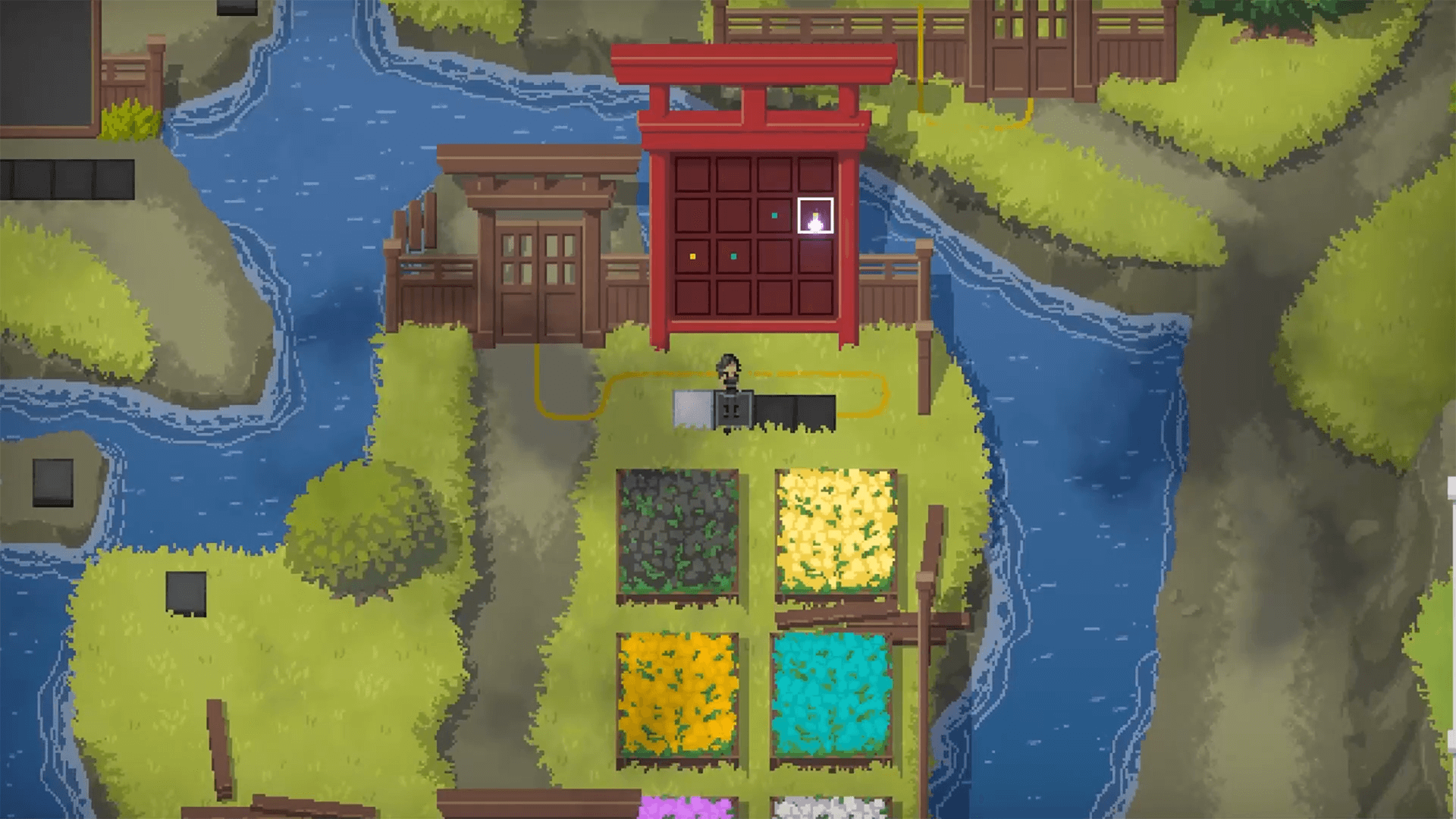

The game begins on a grassy hilltop, with your surprisingly-anime character trapped within the bounds of a glowing 8-pointed star until you at least fumble your way through the basic controls. As you make your way through the opening area, the mechanisms that you’ll be interacting with for the rest of the game are made clearer: standing on a pressure plate activates a puzzle panel, displaying a grid of squares to be toggled on and off with your fairy-like cursor. Once you’re satisfied with your particular arrangement of ons and offs, you commit your answer to find out if the panel is as satisfied as you are.

This opening area of the game introduces one of Taiji’s two flavors of puzzle — observational puzzles — quickly establishing that the environment is not just there to look nice. In fact, the first set of panels are blank, so the information you need to solve them must come from the suspiciously grid-shaped structures you see nearby. Later observational puzzles will instead have you analyzing more abstract objects in the environment, somehow translating their structure into cells on the grid. With each puzzle, the environmental clues become increasingly cryptic, in some cases literally breaking the format of the puzzle and twisting it to its extremes. Of course, puzzles like this run the risk of making you pore over every minor detail, finding patterns that might vaguely fit in the hopes that one of them turns out to be right. However, for the most part, Taiji is extremely unambiguous: once you’ve seen the right detail, you know you’ve seen the right detail.

Even outside these sets of puzzles, your observational skills will come in handy. The most observant players will start to notice many other curious oddities right off the bat — strange shapes in the rocks, patterns in the flower beds, markings on the ground. Are all of these details part of a puzzle? Some kind of thematic motif? A secret? I carried questions like this with me throughout the game, eagerly awaiting the moment those details might reveal their meaning.

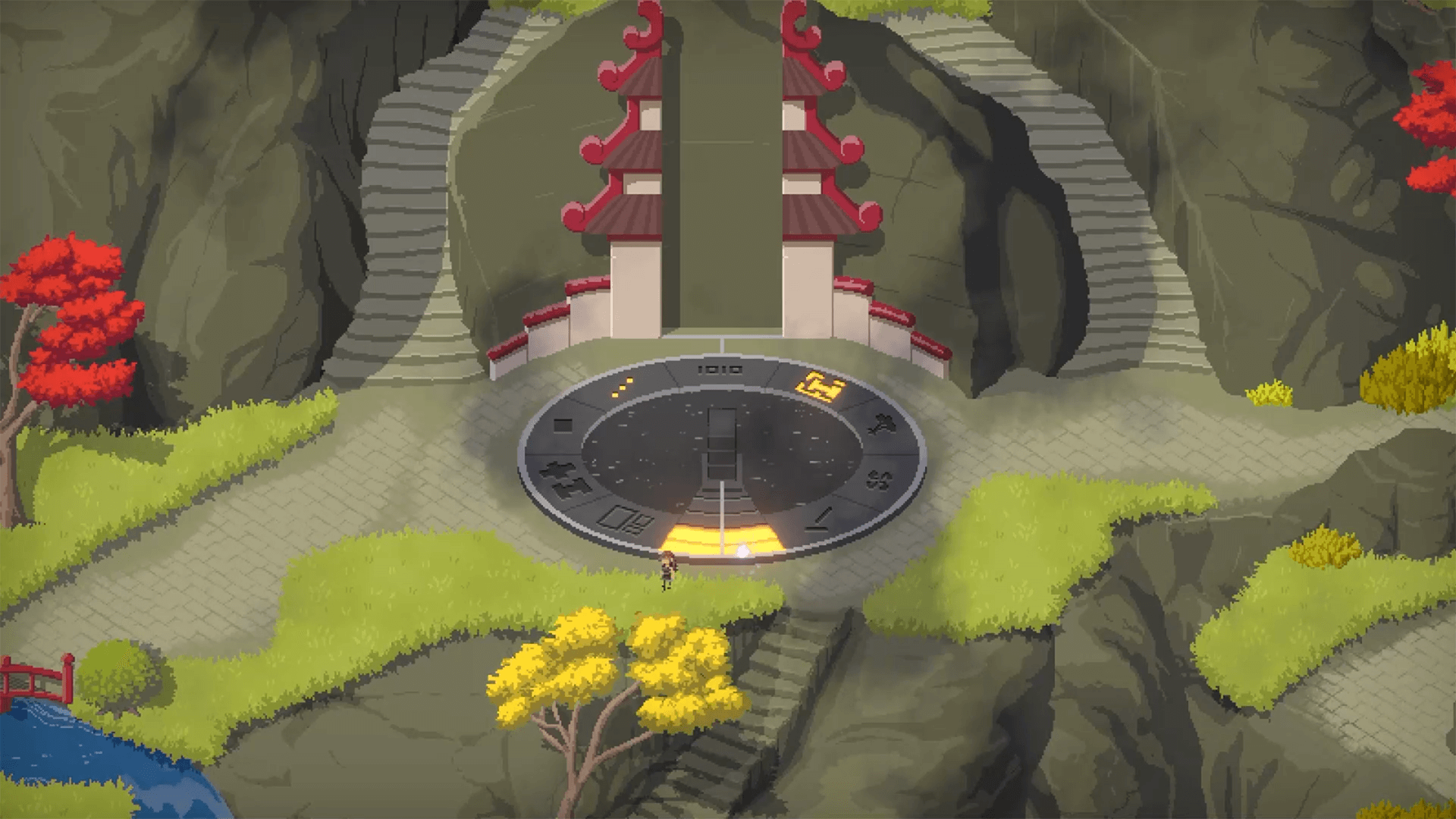

Once you reach the central hub, which also functions as a handy progress indicator, you’re set free to explore on your own. Pick a direction and off you go. I began my adventure by heading north, where I was introduced to what I called the “dots” mechanic. You may, of course, choose a different direction and come across one of the other eight areas, each focusing on a different puzzle type. I was certainly glad to have picked north, however, as it gave me a gentle start that not everybody is fortunate to get. It’s incredibly easy to unknowingly head straight into the more challenging areas of the game, where it might not be immediately obvious that you’re in over your head. Perhaps a few more subtle nudges to guide players would have been a good idea.

The “dots” mechanic I mentioned is an example of Taiji’s other flavor of puzzle: logic symbols. These symbols function as constraints on the grid, each with their own rules about how nearby cells must be turned on and off to satisfy them. If they’re unhappy, they’ll let you know by blinking red — that is, until you encounter more challenging puzzles that expect you to solve them without this helpful feedback. Taiji’s particular set of logic symbols are well chosen, each with enough depth to support an entire area of the game (these areas are significantly larger than the observational ones) and with fascinating consequences when they’re mixed together.

The puzzle mechanics of Taiji, both its logic symbols and observational clues, are tutorialized non-verbally — there are no pop-ups to explain the rules or NPCs to guide you. Instead, it provides you with simple panels on which you can conduct your own little science experiments — make a few guesses, hypothesize about the symbol’s rules, and then hopefully confirm your findings on the following panels — a process that is deeply enjoyable. Of course, this game is a devious little thing, intentionally leading you into a flawed working theory, only to give you a panel where it no longer seems to apply. However, Taiji is also fair. The rules haven’t changed; it’s time to reevaluate your understanding. On a few occasions, this tutorialization process is not quite as incremental as it could be, perhaps relying a little too much on players having had a similar experience in The Witness (which, I admit, is not a totally unreasonable assumption).

Taiji’s puzzle mechanics only falter in a couple of places. In particular, an extension of the opening area’s observational puzzles tries to add an extra layer of depth, but doesn’t manage to tutorialize it well. I ended up guessing my way through these puzzles, which is surprisingly easy to do just by trying what “feels” right, but turning those feelings into cold, hard rules turned out to be too much of a stretch for me. I only learned the intended rules after finishing the game and they’re sufficiently weird that I am not surprised they weren’t one of the options I had considered. Aside from this, I only wish to have seen more interactions between the logic symbols and the observational puzzles — the observational mechanics feel a little too isolated and only really pop up outside of their dedicated zone once or twice.

Taiji does, however, find a few fascinating ways to twist the format of puzzles and breathe extra life into its mechanics. One of its most interesting ideas comes in the form of floor puzzles, which require you to walk a path across them to turn on their cells. Since you must walk a single path without any branches, this turns the mechanics on their head, placing an extra constraint on puzzles that would otherwise be a simple solve. The interplay that this has with each of the logic symbols is fascinating, giving you new ways to make deductions about which cells must or must not be active based on the possible paths you could walk.

Taiji’s logic symbols show their true strength in some of the larger and more complex puzzles. These formidable panels were initially daunting, but quickly became something I looked forward to most. When mingling together on the same panel, Taiji’s symbols interact with each other in fascinating ways. From the disarray of symbols scattered across the grid emerges a beautiful back-and-forth between global and local deductions, as your black and white squares spread across the panel like cells in a petri dish. While some of the smaller puzzles allow for a healthy amount of intuition, these larger puzzles reward careful deduction one cell at a time. Pen-and-paper puzzle fans will find these excellently designed puzzles especially satisfying.

It is with these puzzles that the game’s “mark” feature comes in most useful, allowing you to highlight cells to keep track of your deductions. Marking a cell causes it to emit a fuzzy particle effect, which I found to be a little too indistinct but eventually got used to. In most cases, this feature is especially handy for remembering which cells you know must be turned off, since off is otherwise the default state. In a couple of situations, I found myself wishing I had a different way of marking what I called “Schrodinger’s cells” — groups of cells I knew were either on or off as a whole group, but not exactly which way. I can’t, however, fault the game for sticking with a more elegant interface.

In fact, Taiji’s puzzle panels are more conducive to deductive puzzle solving than in The Witness, simply because they allow you to make adjustments to any part of the grid at any time. Run out of ideas in one corner of the puzzle? Time to start chipping away at another. The Witness did, of course, have its reasons for stubbornly making you draw lines from start to end, but that no doubt held it back from being able to explore these kinds of larger, sprawling puzzles that Taiji does so brilliantly.

While I must acknowledge that there is some semblance of a story and there certainly are philosophical themes — duality, light and dark, all that — this is not the kind of game that entices you along with a narrative. Instead, your reward for solving puzzles is knowledge to use in later puzzles, a sense of satisfaction, and more puzzles — which, let’s admit it, is really the best kind of reward. Why else am I playing a puzzle game? When solved, each panel lights up a glowing cable that leads to the next panel, winding around the game’s naturalistic landscape, through hidden caves and over cliffs. Follow the cables to your next puzzling delight. Gosh, why is it such a joy to follow glowing cables around?

The world that you’re being led through is quite stunning, with carefully hand-crafted 2D pixel art landscapes and architecture, using very limited color palettes to create a flat-shaded art style. The animations of ripples in the water and leaves blowing in the wind are genuinely relaxing. Shadows of clouds passing overhead are a subtle but welcome addition to what would otherwise be quite static scenes, especially when standing at a puzzle panel for a long time. The art style does, however, fall a little short in representing the relative depth between objects. Since the world is multi-layered, with building interiors and caves snaking underneath the surface, this issue can make navigation a little confusing until you become more familiar with your surroundings. Nonetheless, it’s a joy to explore, with each area boasting its own unique visual style. As you wander around, the game’s dynamic soundtrack seamlessly introduces instruments for each area, adding an extra special touch to their unique character.

So much attention to detail can be found throughout Taiji. I have been watching a few others’ playthroughs (it’s extremely watchable) and they’re noticing many things I hadn’t, while also walking right past many of the things I’d seen. Whether it’s the way certain puzzles are subtle variations of each other, visual motifs in the environment, or just the little details that make in-world mechanisms feel more real, there’s a lot to appreciate. There are certainly not many other games where I’ll say “wow, that’s the most perfectly placed tree stump”, particularly when said tree stump is little more than decoration.

Before embarking on my Taiji adventure, I wondered if I would be able to separate it from my experience with The Witness. With unabashedly similar art direction and design sensibilities, Taiji certainly does not hide its affection for the hugely influential game. In fact, some puzzles and mechanics feel like beat-for-beat references, which meant that, in a few cases, what might have been moments of realization were replaced by slightly less impactful moments of recognition; “aha” replaced by “ah, like The Witness”. Despite this, Taiji differentiates itself in the most important ways, maintaining the genre’s all-important sense of wonder and discovery. Perhaps most crucially, Taiji takes a creative approach to its biggest secrets, ensuring the most significant revelations remain uniquely impressive.

Sure, Taiji might be as close to a sequel to The Witness as is possible without actually being one, but like any great sequel, it does much more than simply tread the same old ground. With an exciting new world to explore, layers upon layers of mystery, and excellently designed mechanics that allow for some truly wonderful puzzling, Taiji really stands out on its own merits. Did it give me the chance to play The Witness again? Eh, in a way. But more importantly, I got to play Taiji.

Leave a comment

Hey, cool review

Can you please make a review for Null Gravity Labyrinth ?