Minimalism is having a moment. The recent release Cipher Zero attempts to resurrect the wordless grid-based logic puzzles popularized by The Witness. Workworkwork and other pen and paper offerings go a step further, severing the conversational link between player and designer. 0PLAYER removes interactivity entirely and pushes the “level design as tutorial” ethos to its near limit. The appeal is clear: elegance, purity, awe at the craft and discipline required to shave off anything not absolutely necessary.

Öoo is that, but for the puzzle platformer. It’s also really, really good. What makes it worth dissecting, however, aren’t the ways it spurns clutter and trims the mechanical fat, but the ways it doesn’t.

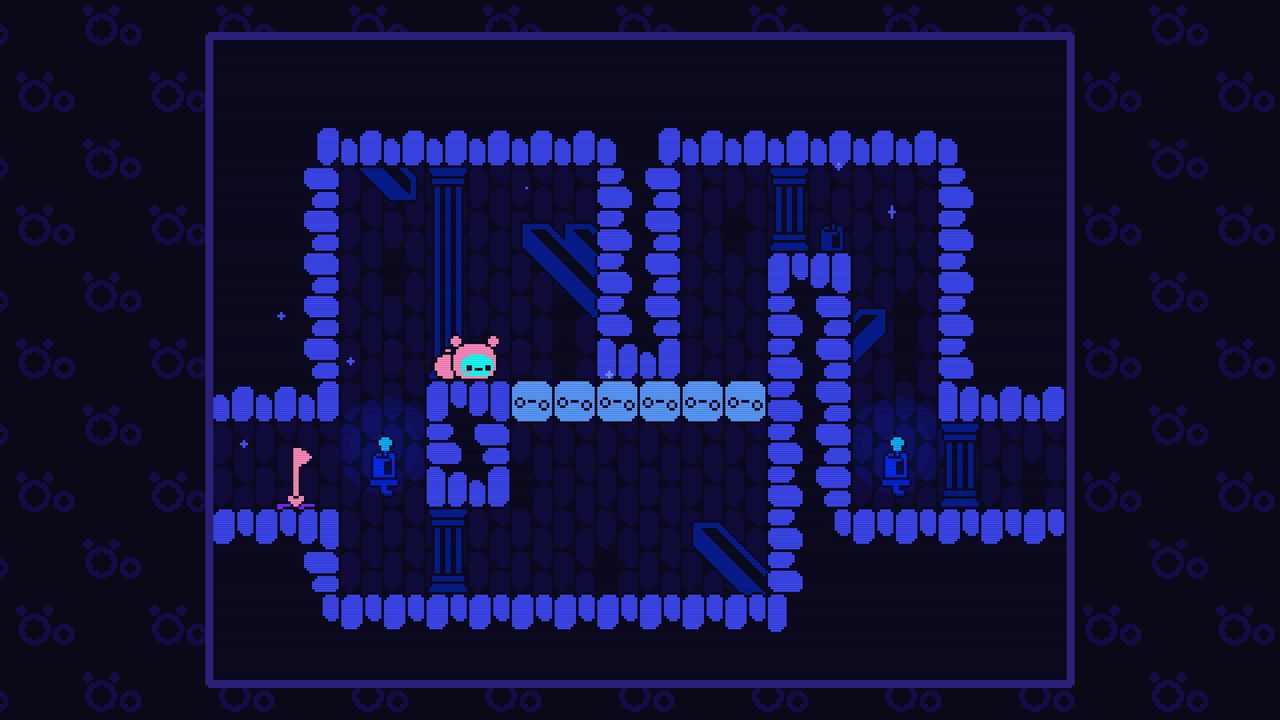

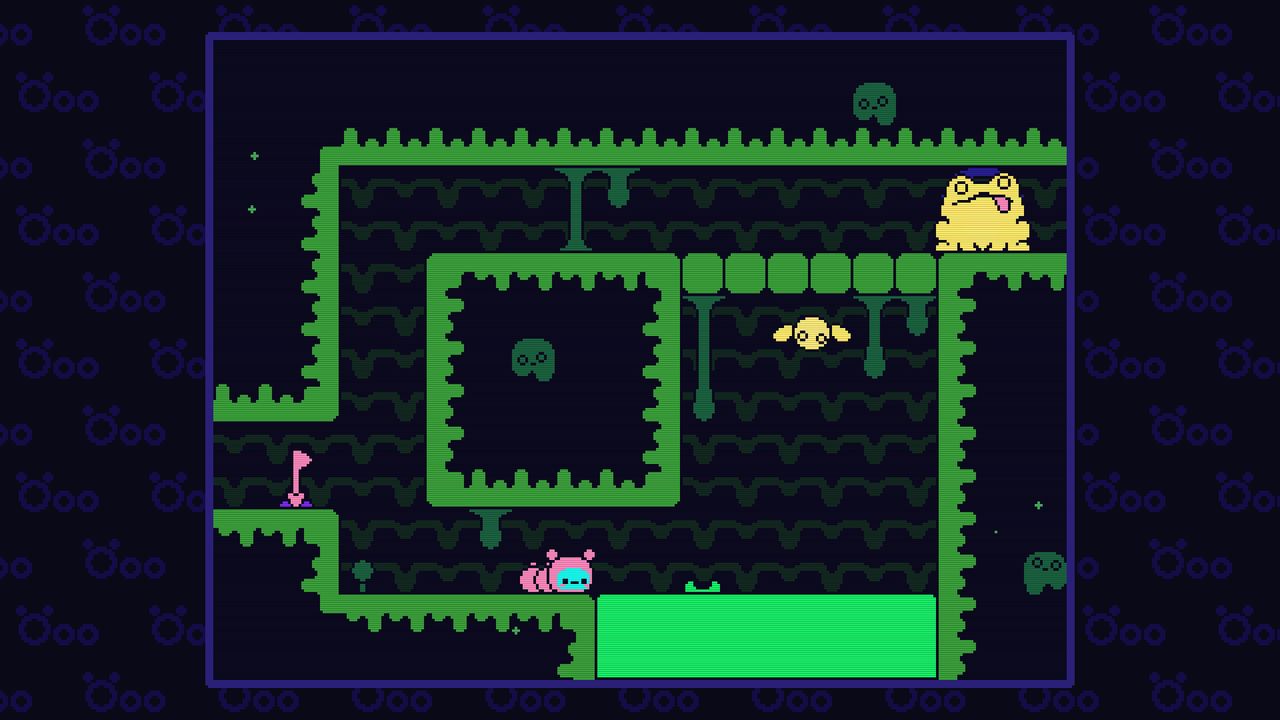

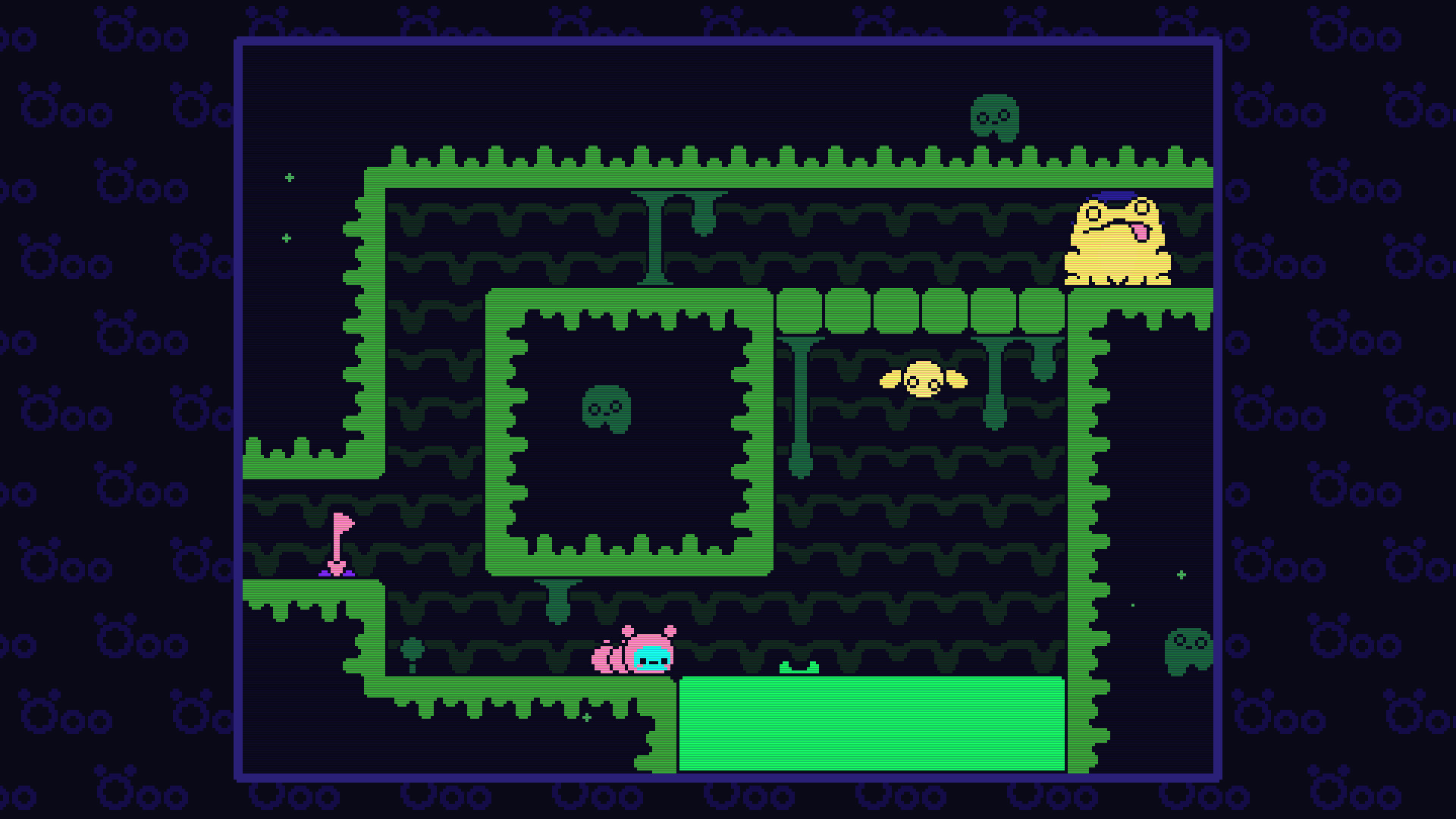

First, aesthetics. With their previous game, ElecHead, developer NamaTakahashi teased at minimalism with pixel art, a restrained palette, and non-verbal menus. Öoo retains those traits, but further crushes down the fidelity of both the visuals (think Animal Well demake), contributed by Hachinos, and the audio (Animal Crossing vibes), by Tsuyomi. While less “juicy”, I favor Öoo’s approach, and I expect it to charm just about everyone who plays.

Just as charming is Öoo’s core mechanic—bombs. Playing as a kind of explosive caterpillar, you can shed a segment of your body and remotely detonate it to demolish walls and propel objects. One of these objects, critically, is yourself—a fact you’ll be leveraging constantly, as most of Öoo’s challenges revolve around traversing its 2D environments.

The movement tech the game forces you to invent reminded me of speedrunning, so much so that I found myself naming techniques in my head. “Okay, so I just have to yoyo this way, then pogo up here and….” This kinesthetic innovation will feel familiar to anyone who played ElecHead, and should satisfy the same itch.

Many people are labeling Öoo a metroidbrainia, but I’m not sure it qualifies. To me, the term implies a certain amount of non-linearity, which Öoo gestures at, but doesn’t ultimately possess. Rarely are multiple solvable puzzles present at one time. Rather, there are typically two paths offered, each guarded by a puzzle—one which the player has the knowledge to solve, and another which they don’t. Progressing along the first path leads to the enlightenment required to tackle the second. And that’s it. Once I recognized this pattern, the game never again felt open-ended. … And that’s okay! In a game with more complex, mentally exhausting puzzles, e.g. The Witness, having multiple available challenges to bounce between helps avoid burnout. Öoo’s puzzles never threatened that, so I didn’t mind its linearity. If anything, I preferred it.

Where Öoo diverges most from ElecHead is with its teaching style. While ElecHead taught its mechanics in part through pictographs, sometimes directly telling the player new input combos to try or rooms to revisit, Öoo adheres far more rigorously to the aforementioned “level design as tutorial” ideal.

To elaborate, Öoo’s teaching style is, “let the player bumble around until they figure out the mechanic,” where the level design is constrained in such a way that said bumbling can only last so long. As the player, this sometimes feels like an act of creativity, yet with so few possible moves, it’s hard to differentiate this “creative process” from brute force. Perhaps that’s why Öoo’s own Steam description uses the term “discover” rather than “invent”. Unlike speedrunning techniques, these are developer-intended, not exploits.

Implemented poorly, this teaching style can make a puzzle feel like the “fossil dig” exhibit at a dinosaur museum. Are you getting some dirt under your fingernails? Sure. But unearthing that trilobite is only a matter of time, dampening the satisfaction when you do. It’s pretend discovery. There’s a spectrum of course, but these hyper-minimal puzzle designs often feel too contrived for me.

Which is why I’m happy to report that Öoo, remarkably, sidesteps this pitfall. How it does this is difficult to pin down. I suppose it’s about tuning possibility space to match the player’s intelligence and patience (and thus, your mileage will vary). Regardless, I never felt overwhelmed by a puzzle’s complexity, nor patronized by its simplicity. A rarity worth celebrating.

Curiously, I suspect this success relies in part on player age, or more specifically, retro video game literacy. A quick note here: Spoilers ahead! I'm going to delve a little further into Öoo's mechanics, so feel free to skip to the last paragraph of this review to read my spoiler-free final thoughts.

See, what makes many of Öoo’s puzzles puzzling in the first place is how they subvert traditional video game expectations, especially video games of a similar 8-bit aesthetic. For example, Öoo’s old school vibes, combined with the fact its map is divided into “rooms” or “screens”, made me mistakenly presume that pressing the “detonate” button couldn’t affect a bomb dropped in another room—setting me up for a delightful epiphany when I realized it did. Younger, less grizzled players who didn’t cut their teeth on games with memory-limited game states likely won’t make this same misassumption, and thus the “eureka” may whoosh right past them. After all, why shouldn’t you be able to place a bomb in one room and detonate it from another? In real life, objects don’t reset themselves when you leave the room. In summary, much of Öoo’s puzzly joy arises not from some inherent mechanical depth, nor from the purity of its design language, but from the sly juxtaposition of retro aesthetics and modern design sensibilities. Again, your mileage will vary.

Which brings us to the catch. Öoo evokes minimalism, yes—but only to a point. It aspires to simplicity, but doesn’t obsess over it. Some people revere games that fixate on a single mechanic and wring every interesting interaction out of it, but Öoo’s approach ultimately isn’t so disciplined. In truth, there are at least four independent mechanics at play, which sometimes interact, but don’t evolve naturally from each other. The teleporter puzzles, for example, feel a bit disconnected, even when they’re integrated more directly in the late game. So too with the green switches. Are they clever? Yes. But to say they all come from the same base mechanical system is dishonest. Öoo’s core mechanic is its movement, and anything that doesn’t explicitly arise from that is ornamental. If Öoo aimed to be truly minimal, it would cut the teleporter and switch puzzles entirely.

All that said, I liked the teleporter puzzles. I liked the green switches. So what gives?

Minimalism is all well and good, but it shouldn’t be the reason to cut good, additive content from a game. Would Öoo be a purer game if it kept solely to bomb-propelled movement for its puzzles? Yes. Would it be a better game? Absolutely not. And that’s where Öoo really shines: it knows when to adhere devoutly to the minimalist dogma, and when to sinfully dabble in excess. That balance can’t come from following the principles laid out in a YouTube game design lecture. It comes from intuition, talent, and experience. It’s why I wholeheartedly recommend Öoo, and why I can’t wait to see what NamaTakahashi does next.

.png)

-1280x720.png)

.png)

-1280x720.png)

.png)

-1280x720.png)

.png)

-1280x720.png)

.png)

-1280x720.jpg)

.jpg)