The atom of the action movie is the punch, or perhaps the kick. In romance, it’s the pregnant pause, the glance, the banter. Detective fiction has the clue. Clues, plausible and correctly sequenced, lead the audience from confusion to understanding. They are stones in a footpath leading inevitably toward truth.

But what if some of those stones are cracked? What if the obvious path, the well-lit one with helpful signage at every turn, leads to something unspeakable? And what do you do when you arrive there? These are the questions asked in The Darkest Files, and it’s a reality the game contemplates. A detective game based on real-life efforts to convict German war criminals in the aftermath of World War II, it takes no scrap of truth for granted.

The Darkest Files is, effectively, nonfiction. Following the collapse of the Nazi Party (NSDAP), many Germans sought normalcy. The high-profile Nuremberg trials seemed like a reckoning, although they only really scratched the surface of the machinery of evil underlying the NSDAP. Even as criminals from the chaotic final years of the war walked free, people accepted that justice was done. Fritz Bauer, prosecutor and a survivor of the Heuberg and Oberer Kuhberg concentration camps, did not. A decade after the war ended, he crusaded against Nazi personnel whose crimes had been buried, making no shortage of enemies among a populace eager to ignore the atrocities he brought to light.

I should add that I’m emphatically not a historian of postwar Germany. My familiarity with Bauer comes down to his Wikipedia page and this game, which doesn’t strive to be a history book. The player takes the role of Esther Katz, a wholly fictional prosecutor working under Bauer. Affordances typical of the genre also appear, speedy bureaucracies where conviction and acquittal ride on the “detective’s” answers to a series of questions. Cases are based on reality, but of course, individual pieces of evidence and lines of dialogue are constructed.

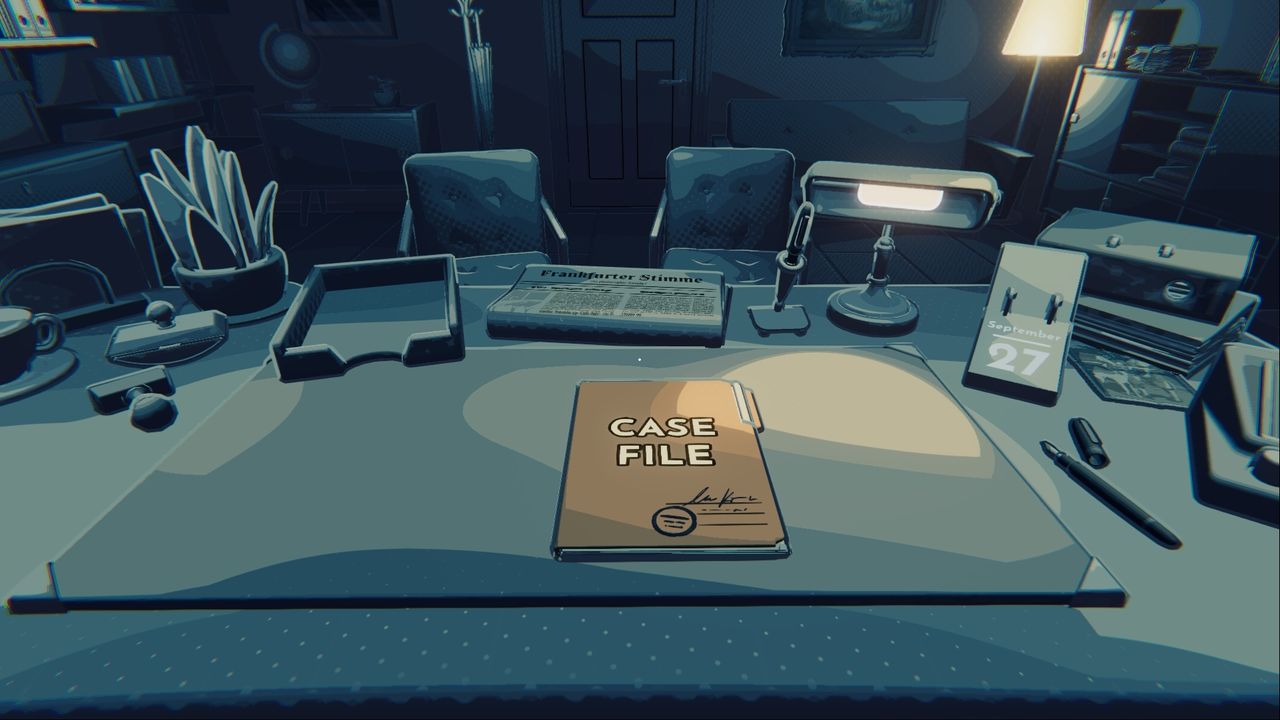

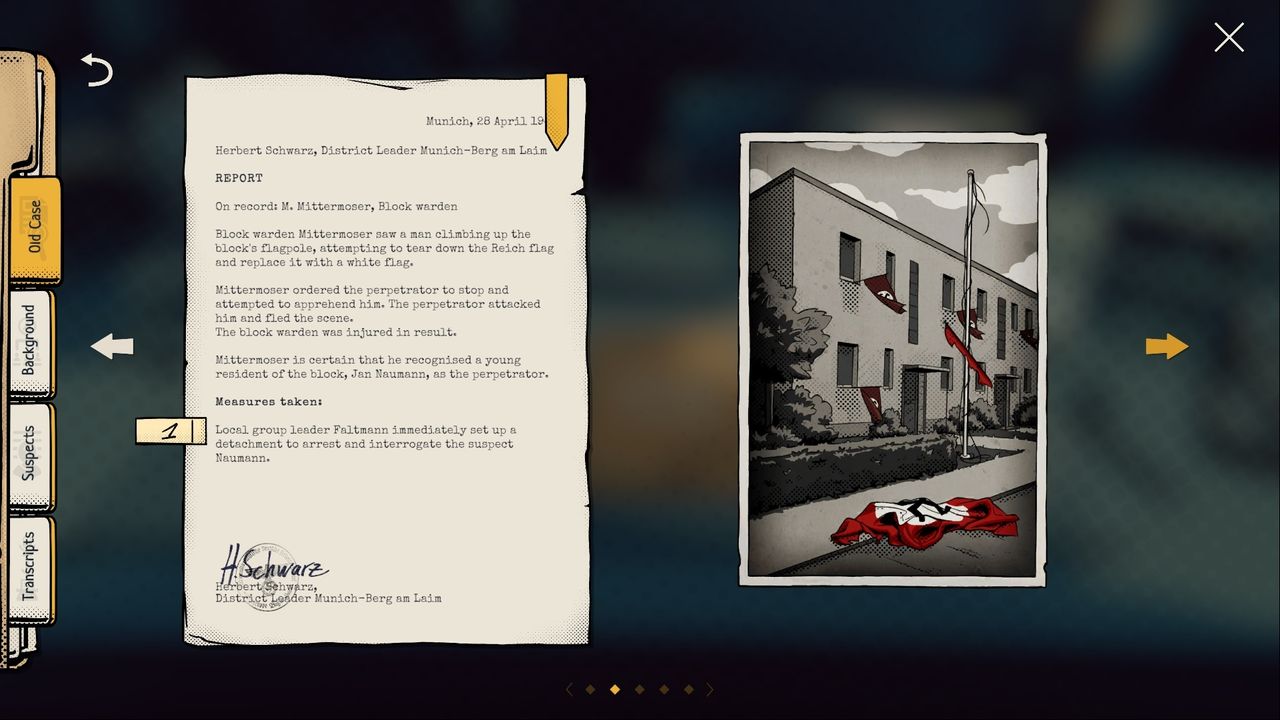

Where The Darkest Files distinguishes itself is in the protraction of that period between receiving evidence and bringing it to court. No piece of evidence speaks for itself, because they’re not, say, fingerprints, or shell casings, or rare snake-bladed switchblades. It’s all paperwork.

Here especially, The Darkest Files’ message is inextricable from its historical basis. Its fundamentals of the detective game are solid, but if the execution orders and arrest reports were all undersigned by the clerks of a fictional autocracy, I’m not sure I would be writing about this game. There is something powerfully affecting about searching the archives for a case file, only to stumble upon the reference number for the criminal record of Adolf Hitler. Details like these keep the player grounded in the substance behind the genre. It is not a subject the game takes lightly.

Detective fiction’s traditional relationship to evidence is thus inverted. In a typical detective game (cue a link to Thinky Games' best detective games list), policework forms the bedrock of the case. Autopsy reports outline the facts of the victim’s death; suspect profiles provide descriptions of suspects. Truth is found by peeling back the lies of guilty people.

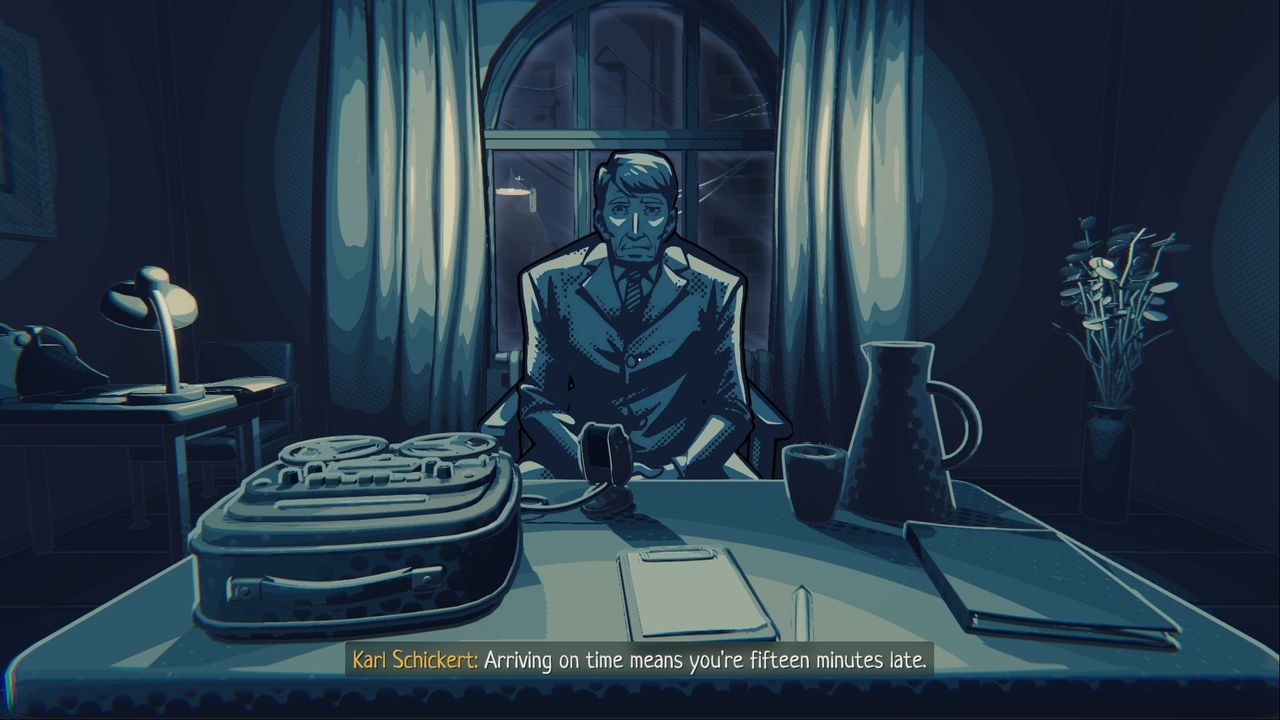

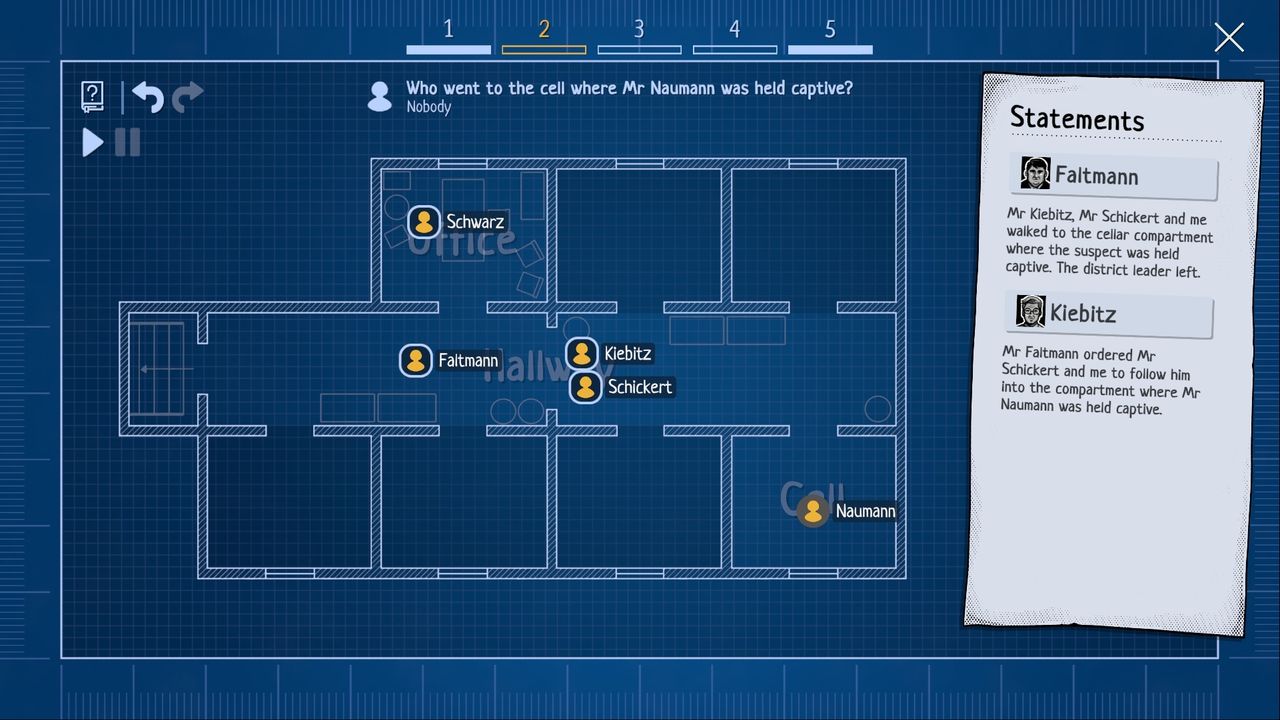

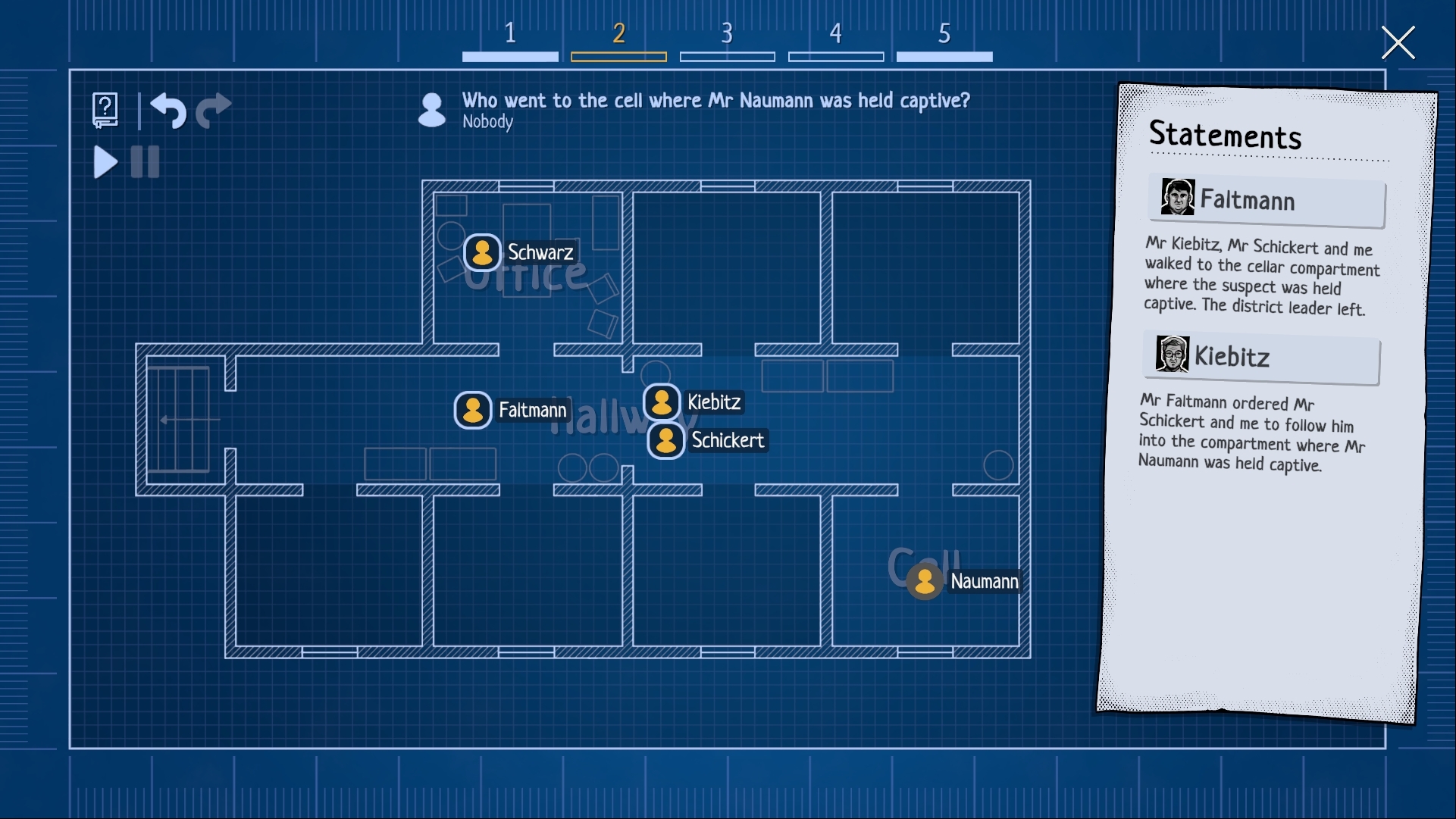

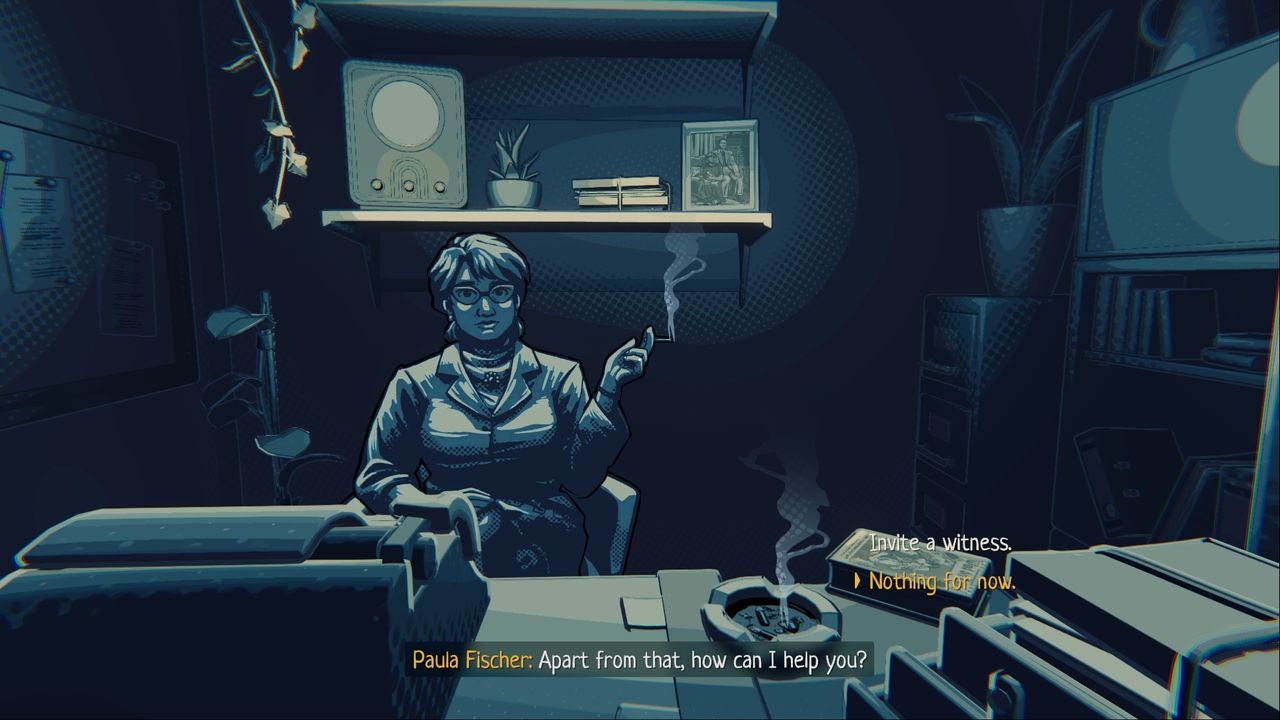

In The Darkest Files, policework can’t be trusted. Unreliable bureaucracy is exactly the problem you’re trying to solve. Beneath the NSDAP’s official-sounding verbiage and curt dismissals is an engine of petulance, human cruelty disguised as justice. Testimonies are often far more illuminating. When Katz brings a witness in for questioning, the scene dissolves into a memory in which she can walk and interact. The player literally inhabits the witness’s version of events, details of the scene subtly shifting based on who’s telling the story and what they’re trying to get you to believe. Not every contradiction means something: memory is flawed, and even outright lies are rarely organized. People lie to cover for someone, or to make themselves look good, or because they are too afraid to acknowledge the truth.

Katz, and therefore the player, confronts the truth head on. The Darkest Files takes the position that truth is not the absence of deception, but a positive assertion made in the face of ignorance. To make Esther’s case, she must assemble three pieces of evidence that all build to the same conclusion. Success doesn’t come from spotting a lie, but from constructing a narrative—and, crucially, this narrative differs in kind from the one propagated by power. The NDSAP “desk murderers” (as Bauer calls them) bludgeon the truth into submission with sheer authority. They present simple answers, threaten violence, and make their own outcomes seem like inevitabilities. Katz’s truth admits the human failing of memory and morals, doesn’t blink in the face of a signature, embraces complexity, and gives equal purchase to all perspectives.

The Darkest Files is, at times, held back by convention. Its characters are legal drama characters, and it engages in a bit of hero worship with regard to Fritz Bauer, diluting his real greatness by neglecting to distinguish between history and hyperbole. The verification system, which states objectively when a correct conclusion has been reached (compulsory for any detective title this side of Pentiment), glares a bit when juxtaposed to the rest of the game’s commitment to subjectivity. Most of its sacrifices seem directed towards making the game function as a playable game rather than an edutainment product.

Any education the player receives comes after the trial concludes. A few paragraphs appear explaining the real case it was based on. I was astonished by how closely the developers preserved relevant details of the mystery, even considering the changes that were made to suit gameplay. Each description ends with the disclaimer that names have been changed to protect victims. “But this story remains true,” it says. “And it is one of many.”

Truth, The Darkest Files suggests, is not a quality but a conclusion. “Clues” do not themselves deliver justice. As Esther Katz, you must not only find pieces of truth, but assemble them into a shelter over those targeted by fascism. That the stories told in this game are fictionalized has little bearing on their truthfulness. While prejudice remains, stories like them will expand to fill the empty space of ignorance.