When analyzing puzzle design, many describe how a puzzle game can give them the satisfaction of 'feeling smart'. For others, it's almost the opposite; puzzle solving isn't just a gateway to feeling smart but to actually being smart. While I lean in the latter's direction on the matter, I think puzzle games also hold a crucial third value, which is often overlooked. For me, a puzzle game isn’t a highbrow dopamine dispenser, nor a crash course in critical thinking. It’s a magic show.

If you’re a fan of stage magic—or just watch a lot of late-night talk shows—you’ve no doubt encountered Penn and Teller. Penn, the outspoken showman. Teller, the silent god of sleight of hand. They’re the longest-running headlining act in Vegas, and deservedly so. Both genius and humble, they appeal to diehards and couch-surfing casuals alike. The algo loves them too. Clips from their TV show Fool Us (which just aired its 11th season) keep materializing unexplainably in my YouTube recs.

However, the clip I want to talk about isn't from Fool Us, but from the duo's 2018 “Vanishing Chicken” appearance on The Tonight Show. I'll leave a link below (and I encourage you to watch it), but in a nutshell, the bit is framed as a lesson in the art of magic (a common theme in Penn and Teller’s acts). The performance teaches viewers how magicians use misdirection, or as Penn defines it, “a curating of attention,” to bamboozle unwitting audiences. By “leaking” us these forbidden tricks of the trade, the two inflate our egos, our sense of shrewdness and proficiency and immunity to that same “curation”. Put simply, they make us feel smart. That is, until Penn whips off the curtain, and the band plays, we’re left gobsmacked by a reveal we never saw coming, one that has us scrubbing backwards in the video and asking, “How did I miss that?!”

Jonathan Blow, game developer of Braid and The Witness, is famous for making his players ask - and sometimes scream - the very same question. The Witness contains his most famous illusion (and perhaps the most famous in all of puzzle games), but he’s been pulling rabbits mimics out of hats since he burst onto the puzzle game scene in 2008.

In the developer commentary for his freshman effort, Braid, Blow uses a familiar term, “misdirection”, several times to describe what might as well be the same technique applied to puzzle design. Speaking about a mid-game puzzle—a time travel twist on the classic keys-and-locked-doors conundrum (32:40)—he explains:

“There’s misdirection here in the sense that we give you the wrong key first. And, in fact, when I give you the wrong key, you haven’t even seen the other key. But usually people are just going to start making progress on the puzzle. So, they open the first gate that can use with the key that they can see, and then they start looking around like, ‘What’s down the ladder? Oh there’s another key. Great.’ … It’s set up to encourage people to do it wrong.”

Three doors. Two keys. The only question is the order in which to apply them. The more distant key, of course, is the one the player needs to start with, but by the time they find it, they’ve already used the first key. And just like that, the trap is sprung. Misassumption locked in. All that’s left is to blindside the player with their hubris.

Unsurprisingly, the climax of Penn and Teller’s “Vanishing Chicken” act doesn’t coincide with the peak of the audience’s intellectual ego. The opposite, in fact. When Penn whips off that curtain and reveals the gorilla, we’re made to feel not smart, but stupid. And yet we’re thrilled. We applaud and cheer, as if we’ve been given a gift.

Less predictably, the same truth holds for Braid’s keys-and-doors puzzle. The moment I’d classify as the climax, the most impactful and memorable moment, isn’t the solve itself—the fabled “eureka”. Rather, it’s the moment when the player realizes what looked easy is actually difficult, when they stare at the screen and ask, “How is this even possible?”

Grimoire

Workworkwork, the latest release from beloved Slovenian puzzle auteur Blaž Urban Gracar, has the Thinky community buzzing. Like Blow, however, Gracar has been conjuring conundrums for years. In 2023 he published Abdec, a pen-and-paper puzzle book, which, like Braid, is a magic show in disguise.

Equal parts cute and cryptic, Abdec tasks players with jigsawing various polyominoes—each associated with a letter of the alphabet—into increasingly complex grids. Being a rules-discovery exercise, though, packing polyominoes is merely one facet of the challenge. The primary objective is to infer the information the book teasingly withholds: the shape of each polyomino. This is made possible first, because each puzzle is guaranteed to have a singular, unique solution, and second, because the rules are consistent across puzzles.

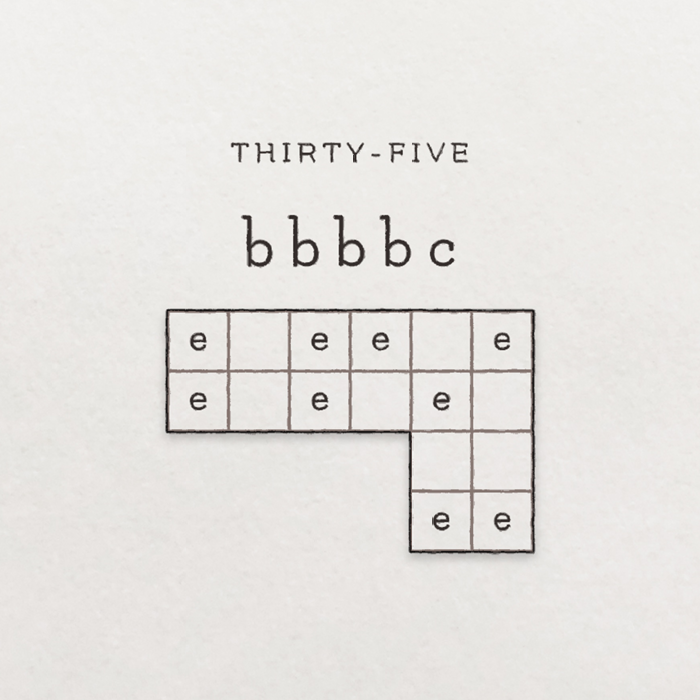

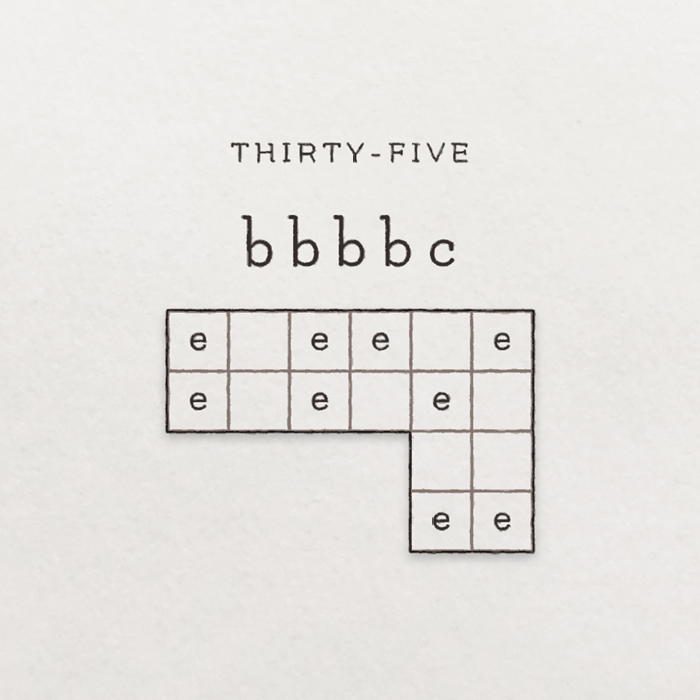

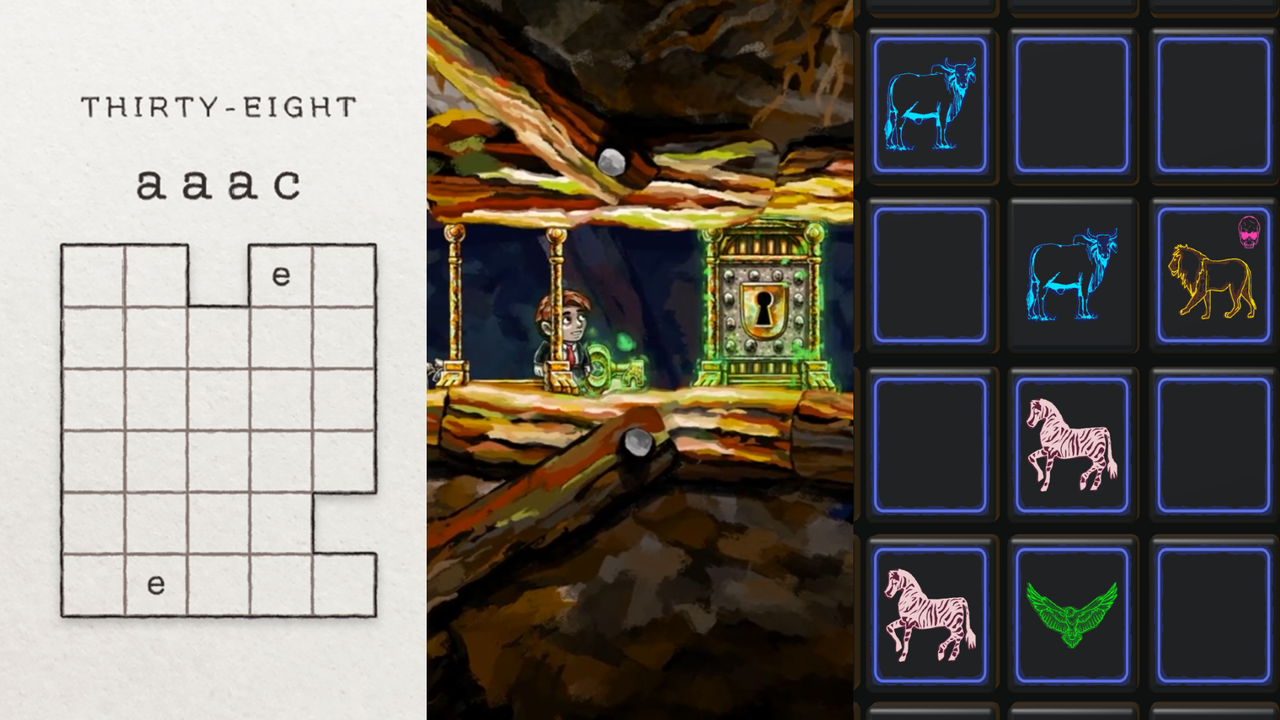

Abdec’s most mind-bending illusion begins at puzzle thirty-five, with the introduction of the polyomino “e”. Fortunately, e’s shape is trivial to infer. (Just fill up the grid!) Suspiciously trivial, one might say in retrospect, but during my playthrough, I ploughed ahead without consideration. If it works, it must be right, I thought.

And it kept working. Puzzles thirty-six and thirty-seven also succumbed, with a bit of effort, to this same rule interpretation. Confirmation, I thought. My conception of “e” grew rigid. Calcified. Confidence led to comfort led to certainty. Then I got to puzzle thirty-eight.

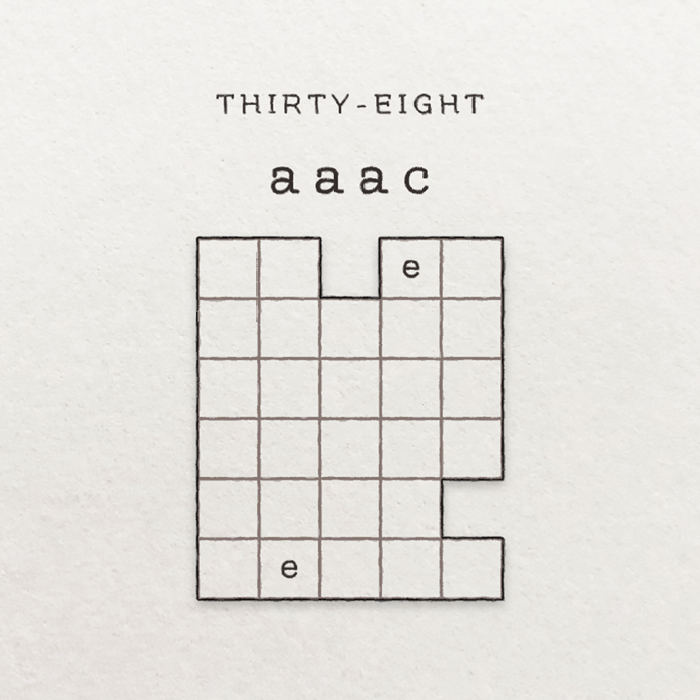

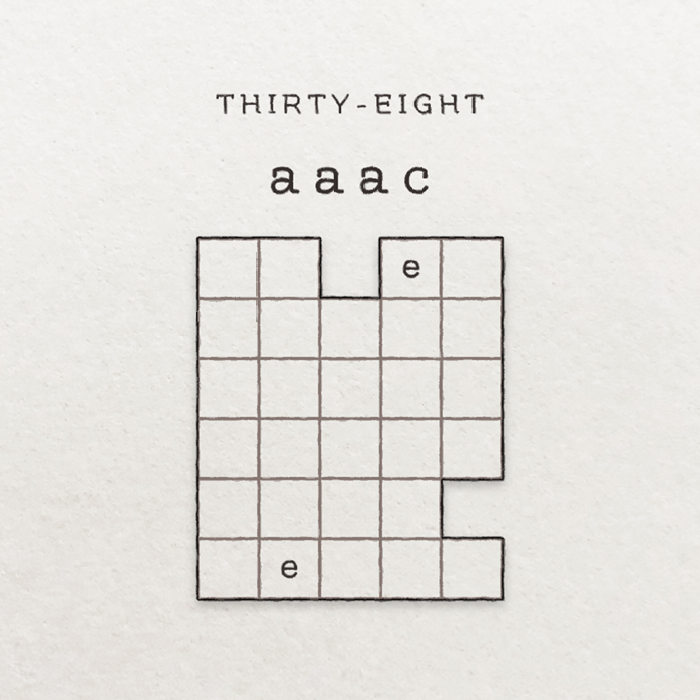

Puzzle thirty-eight was impossible. I stared at it for hours, sketched out countless failed attempts, whittled my eraser to a nub, but the puzzle refused to budge. This is Abdec’s gorilla. “You think you know everything?” it jeers at you while pounding its chest. “Think again.” And I did think again. The puzzle, as I understood it, was impossible. Except just like with the “Vanishing Chicken”, there were constraints on the scenario that made me certain it was possible. This was a popular, well-loved puzzle book. An error like this couldn’t have made it into the final release.

A magic trick is a paradox, a koan, a surgical retractor for the mind. And that’s what puzzle thirty-eight did to me. I felt my mind stretching open, turning inside out. “It can’t be possible, and yet it can’t not be possible.” I was experiencing the mental equivalent of a “runner’s high”. Intellectual endorphins, if there is such a thing, flooding my nervous system. After much backtracking and reexamination, I identified my misconception and corrected it. I learned the true shape of e. Aha! Eureka! Huzzah!

But that wasn’t the moment I fell in love with Abdec. That came earlier, when the game showed me that something which looks impossible could in fact be possible, when it blindsided me with my own closed-mindedness. Not “aha!”, but “voila!”.

Puzzle games, at their most valuable, don’t make us feel smart, nor “be smart”, but feel stupid—gently, in a good-natured way. They make fools of us. Dazzled, starry-eyed fools. And with ignorance comes bliss. Well…most of the time.

House of Cards

Puzzles, like magic tricks, don’t always work. If we’re going to tout misdirection, we should also consider how it can fail.

Zoobotics, by tjm (better known for CERT, another fantastic pen-and-paper puzzle book released in 2023), describes itself as “a short, challenging animal-matching puzzle game.” In a single continuous mouse-drag, players must shuffle tiles around on a grid to group animals. Constraining this is the fact that once a tile has been traversed, it becomes fixed in place, now acting as an obstacle.

For a jam game, Zoobotics is packed with ideas. What starts off as a trivial drag-and-drop exercise soon evolves into a pathfinding chess match. New mechanics come hard and fast, never wasting the player’s time with unnecessary repetition or clutter. My favorite puzzle was level IV, which took me nearly an hour despite its apparent simplicity.

When I play puzzle games this minimalistic, this restrained in their design, I can’t help but think of close-up magic—the genre of illusion performed in clear view, within feet of the audience. (Where minimalist puzzle games almost invariably involve 2D grids, close-up magic almost always involves playing cards.) This intimacy makes for heightened impact. The audience can’t blame their bafflement on smoke and mirrors, so that bafflement hits all the harder.

On the other hand, this focused perspective hinders misdirection. A magician can’t shout at the audience to “Look over there!” if there’s nowhere to look. This means a lower margin of error. Precision is everything, and a tiny slip-up can turn what should be gasps of astonishment into awkward, confused coughs. Unfortunately, during a particular trick in Zoobotics, that’s exactly what happened.

Puzzle VII introduces lions, which, when matched with each other, have the bothersome effect of killing off other adjacent animals. This leads to animals being stranded without a mate—a failure state in the game. The lion mechanic, however, is a subtle misdirect. While players might assume that the death of any animal guarantees failure, this isn’t the case. If the lions cull all instances of a particular animal, the puzzle remains solvable.

Getting the wrong idea here won’t limit the player at first, but in level X, it comes back to bite. As tjm explained to me, “The intended incorrect interpretation is ‘every animal must be adjacent to another of the same kind; if any animal is killed, the puzzle is failed’. That’s reinforced through negative SFX when an animal dies. Level X is impossible under that interpretation, and the player must realise that the correct rule is ‘every living animal must be adjacent to a living animal of the same kind’. Unfortunately, it’s possible to solve level VIII in a way that makes the correct rule clear.”

Which is exactly what happened to me. Through sheer chance, I solved level VIII in a way that spoiled the correct interpretation of the rule, robbing myself of the “voila” moment in level X.

Level X didn’t frustrate me—I got a dopamine hit out of it at the very least—but neither did it astonish me. I missed out on the mind-expanding moment tjm aimed to elicit. Whoosh. Magicians deal with this threat through extreme attention to detail( not to mention heaps of trial and error—playtesting, basically). That, and they have plan Bs in place in case the audience doesn’t take the initial bait. They build routines with flowcharts, diverging paths, backup strategies, tricks within tricks.

Game designers have it both easier and harder. Easier because the stakes are lower—for a professional magician, accidentally revealing the secret to a trick could decrease the appeal of their show, and thus lead to financial loss. Harder, because the game designer isn’t present when the audience is engaging with the product, and therefore must ensure the game can handle any mishaps automatically. A gargantuan task, especially if you’re crunching over a weekend and can’t afford QA.

Four years post-release, having witnessed the level X twist landing—and not landing—for various players, tjm suggests a simple fix: “If I revisited the game, I would modify level VIII so that there were no solutions with dead animals.”

I should point out that Abdec’s “e” illusion could just as easily go over the player’s head for the same reason. While it landed for me, it’s impossible to know—perhaps even for the designer—what percentage of players this kind of technique works for. Maybe that’s a hazard we have to accept. After all, a magician can never be sure whether an audience member is clapping out of actual astonishment or simply because they don’t want to stand out in a crowd. Fortunately, despite missing out on that Level X twist in Zoobotics, the game had plenty more up its sleeve that I enjoyed. Give it a look!

Bringing it Back

I was in elementary school, on the playground at recess, when I first learned the truth about Santa Claus. In high school, I studied outer space: boundless, but according to my textbook, oh so certainly barren. Just last year, I researched quantum mechanics, and learned about the theory of faster-than-light communication—and the rules that state with utmost surety it can’t be done. Puzzle games may be able to make us smart, but intelligence has its downsides. The more you understand, the less there is to be surprised by. Sometimes, knowledge isn’t power—it’s disillusionment.

Magic tricks—and the puzzles that evoke them—offer a cure for that. Executing them requires both delicacy and timing, but when they work, they have the power to rekindle the childlike belief in the unexplainable, the impossible. That they themselves are deceptions doesn’t invalidate them, because the truth they remind us of is absolutely real: if you take the time to look, to set aside your expectations, to detour from your typical routine and witness things you never have, you’re sure to encounter something marvellous. The older and more experienced I get, the more precious that spark of ignorant possibility is.

Faster-than-light communication is impossible. Abdec’s “Puzzle Thirty-Eight” is impossible. Unless it isn’t.

Puzzle game designers, please, don’t be afraid to exercise a little “attention curation”. Sure, stroke our egos. Teach us to be better thinkers. But most of all, remind us that even at our intellectual peak, we’re capable of error. Show us we don’t know everything. Slap us with our own misconceptions. Fool us.

.png)