“Interface Mystery Adventure” are three of my favorite words, so I was pleased as punch to see all three applied to the recent Next Fest demo for Desktop Explorer. Most games try to make their interface as transparent as possible, so the derring-do to make UI the primary design focus always grabs my attention—and, as seen in my all-time favorite Hypnospace Outlaw, such an offbeat focus can create some of the most offbeat, interesting stories. We’re long past the point where UI can do all the heavy lifting, and where Desktop Explorer plans to extract real novelty in the genre remains to be seen.

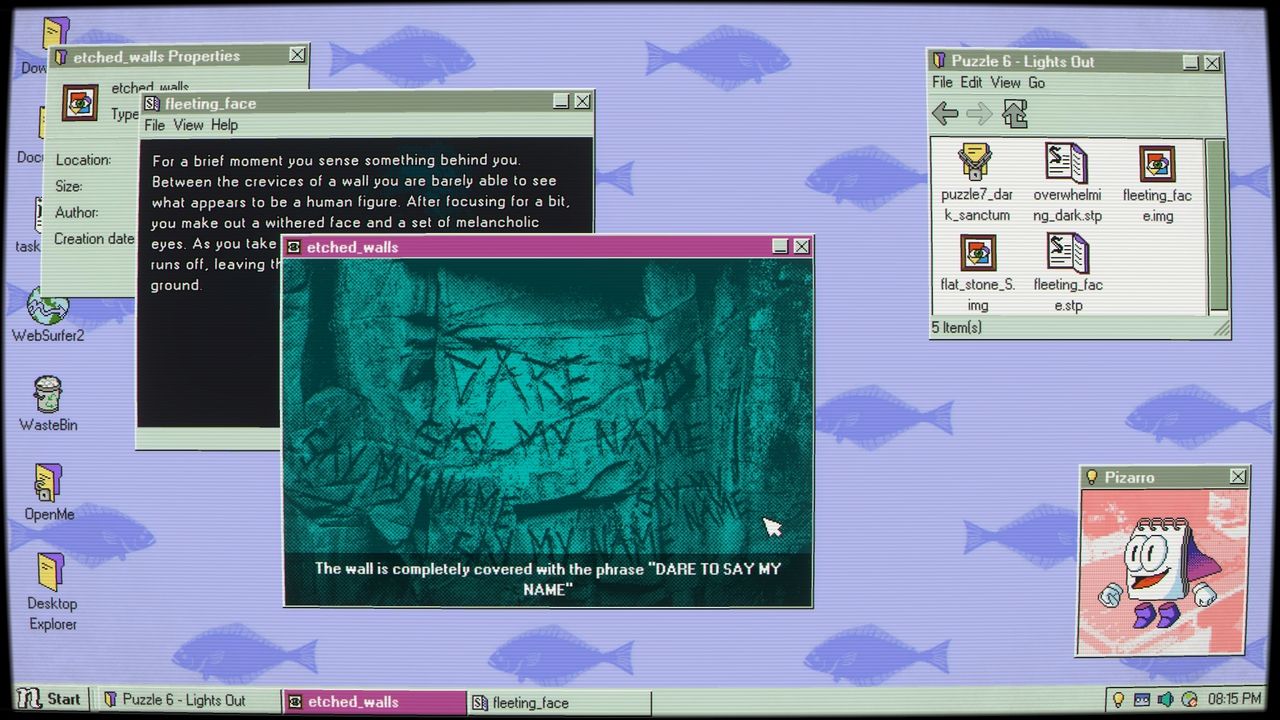

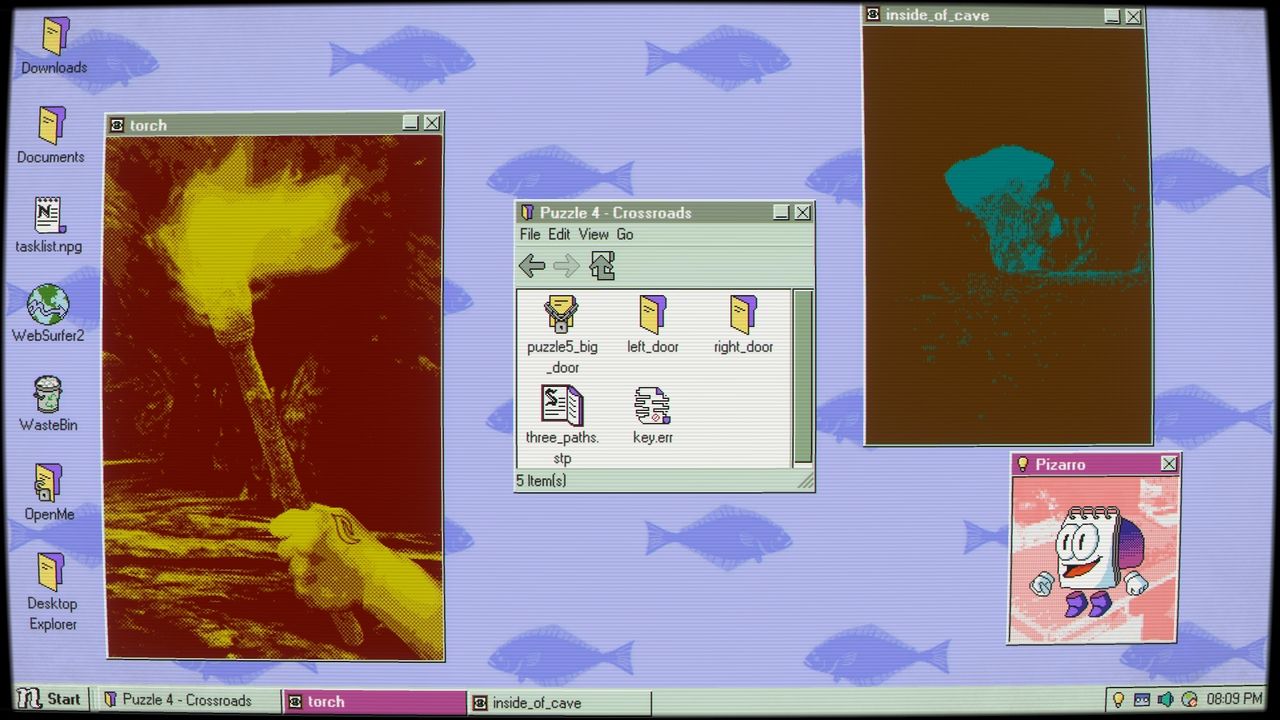

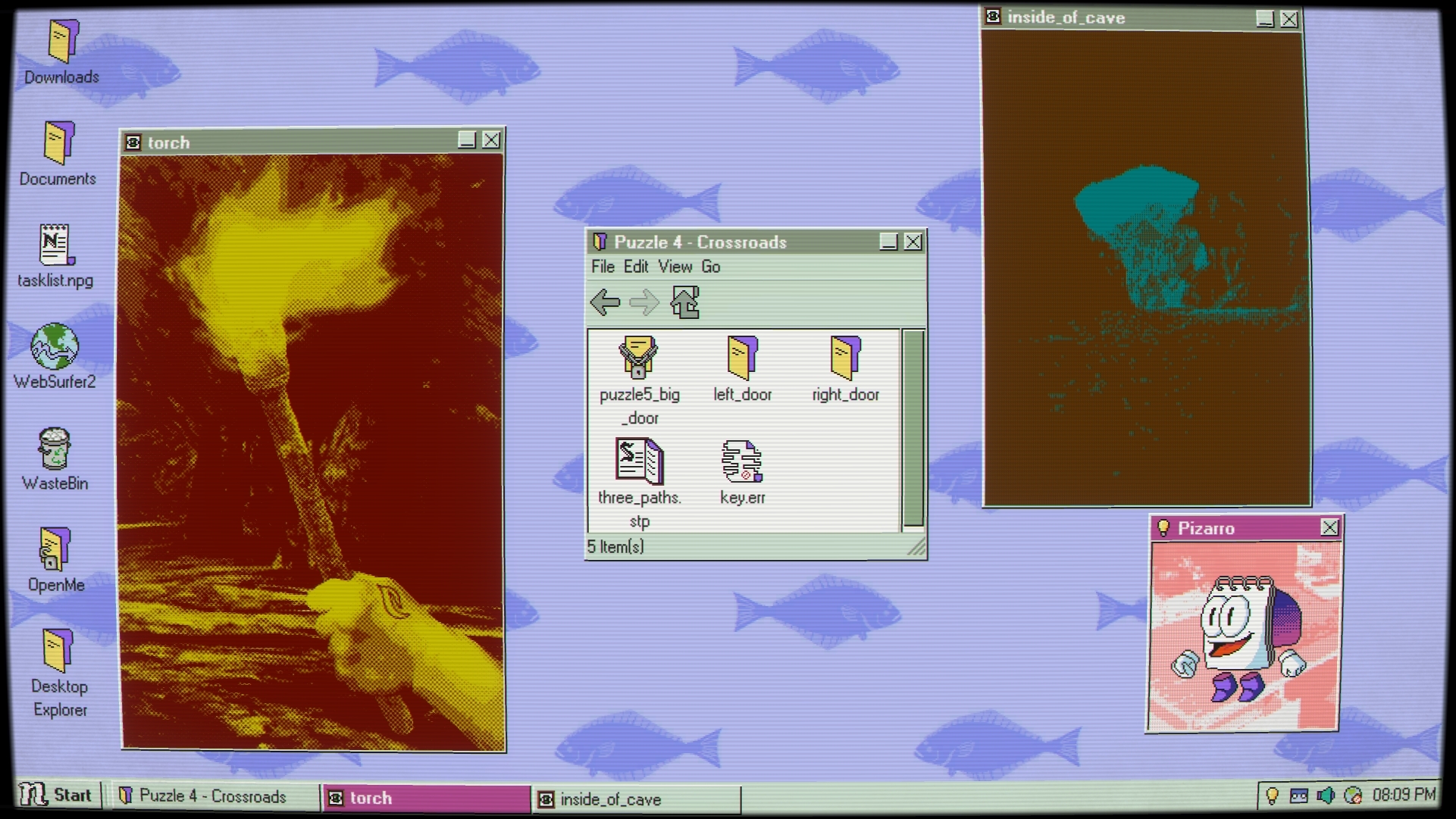

To start, the demo distinguishes itself by casting the player not as the main character themselves, but as a girl we come to know as Guppy. Inheriting her uncle’s old PC, she finds a cryptic diary entry urging her to unravel the mystery of a game called Desktop Explorer. The game-within-a-game is an old-school text adventure played in the computer’s file management system. Files contain the passwords to locked folders, which contain more files and more locked folders, and so on and so on. Desktop Explorer is framed as a descent into a dungeon, and while that’s exactly how it plays, it’s not for the reason Guppy expects. As she plunges deeper into the subfolders of the game, out-of-place and corrupted files unearth a genuinely haunting tale.

Skimming a synopsis of Desktop Explorer (the irl game, not the metagame), I’m keenly aware that similar games have trodden this same path. Sara Davis Baker’s video “Obsessive Horror Games” outlines a handful of titles that seem alive, acknowledging the player directly to scare them.

Desktop Explorer feels neither derivative nor redundant on a first impression. The interface itself—a Y2K-coded operating system called NextOS—is far more than a facade meant to lure players to a ghost story. It functions more or less as a real operating system, allowing you to move, rename, rewrite, copy, and even delete files. You can view hidden files and source code. You can actually type, and you need to!

These may seem like small victories, and to be fair, NextOS isn’t a complete sandbox. Guppy doesn’t have the admin privileges to softlock herself. Puzzles aren’t open-ended (or they weren’t in the section I played), so it’s not like I was coding or manipulating files for reasons beyond convenience. The depth of Desktop Explorer’s interface excites me because it’s a sign that the game is taking its ideas seriously, not just scoring points off its niche premise.

It also signals that paying attention will pay off. Every element of the OS is functionally designed, meaning that every inch is fair game for hidden information. As early as the bootup screen, I notice an aquatic theme: a logo for “Ocean Tide Pollution Prevention” is prominently displayed; the company that makes NextOS is called Spiralsoft, referenced in the curling seashells of the default desktop wallpaper; Guppy’s uncle takes the screenname Halibut, and he gave her her nickname during a fishing trip. My point isn’t that all of these threads are going somewhere revelatory, only that I became excited about the game’s narrative elements as early as the bootup screen.

The roominess of Desktop Explorer’s interface injects its puzzle design with constant creativity. I can’t say for sure whether I had difficulty solving any one puzzle, but each required me to explore a new nook of the fictional computer’s functionality. The demo doubles as a tutorial for basic mechanics, so it’s not yet clear whether these functions will be one-and-done affairs—whether, for example, the password I find by resizing a text window will be the only one that makes use of that trick—or if they’ll carry forward. At the same time, I definitely didn’t feel the game was running out of ideas. Even while exploring the settings, I saw a maze screensaver that I could immediately imagine as the setting for a future puzzle. Dozens of little corners of the interface filled me with this kind of excitement.

One final way I see Desktop Explorer distinguishing itself from other haunted computer games, and one you should take as a warning, is that the game is scary. I’m no longer all that rattled by fourth wall breaks in horror games. I know the video game can’t get me. But recall that Desktop Explorer isn’t about me: it’s about Guppy. And in a very short space of time, it got me to care about and be scared for her. Placing the story within the game paradoxically raises the stakes—a lesson other devs in this space could take heed of. At the very least, it makes for a refreshing story. Refreshing and chilling. Like a glass of ice-cold poison.

Outersloth, the indie game fund backed by Among Us developers Innersloth, has thrown its support behind Desktop Explorer, proving once again its keen eye for strong, personality-driven design. It’s a highlight of their current roster, and one I’ll be looking out for in 2026.