Word Play is the latest from Mark Brown of Game Maker’s Toolkit, following up on the release of Mind Over Magnet late last year. This time around, GMTK is serving up a bite-sized, uber-replayable spin on Scrabble. The game on its own is a ton of highly polished fun with words—but it also has me excited about the recent evolution of wordy games in general. After dusting off my actual degree in linguistics (and it was quite dusty), I’m pleased to revisit some of my favorite games about having fun with language.

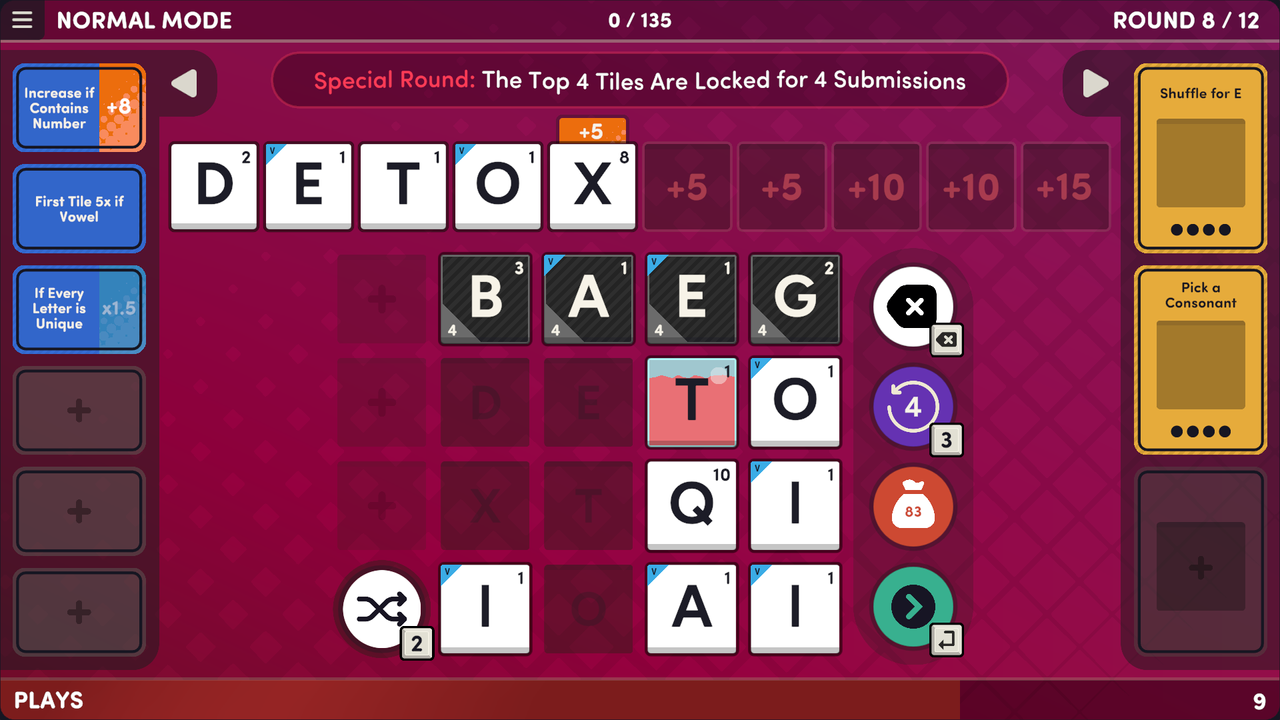

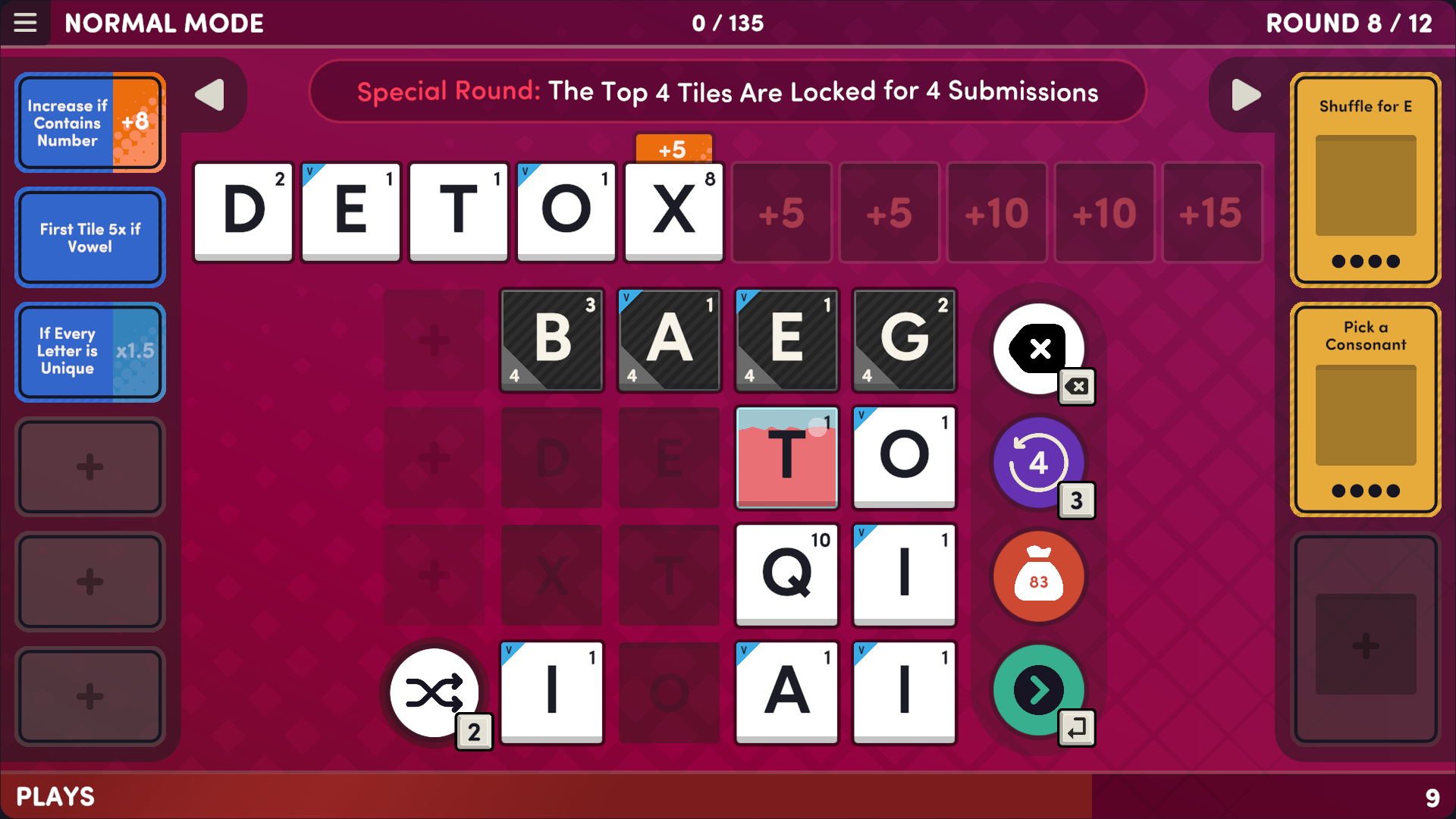

My first recommendation is, surprise surprise, Word Play. It’s new, it’s shiny, and with an elevator pitch like “Scrabble Balatro,” it’s worthy of any word nerd’s attention. The gist is simple: given sixteen randomly shuffled letter tiles, your goal is to hit a point threshold by spelling words with the tiles provided. The end of each round gives you the chance to pick out a special tile, consumable upgrade, or perk, most of which grant additional points when fulfilling certain conditions, like spelling a word with double letters or placing a particular tile at the end of a word. And you’ll need to meet these conditions if you hope to match the ever-rising point threshold each round.

While Balatro is a great comparison in terms of structure and overall goal, the kinds of considerations I made moment-to-moment in Word Play were vastly different from other score-chasing roguelikes. Namely, Word Play’s final scores are much smaller, and progression is linear rather than exponential. Most of the upgrades I came across were additive, while score-multiplying perks were harshly restricted, either by rarity or by the conditions required to use them. In the rounds I played, I never reached the point where the engine I built could reliably run on its own. My ability to pull unwieldy words from the jumble remained at the forefront.

Brown managed to turn Word Play around in just seven months, starting in December with the annual GMTK game jam. But even this much shorter development window wasn’t without turbulence. In a video outlining Word Play’s development, Brown says that “disaster struck” in mid-February with the announcement of two other score-chasing roguelike word games: Wordatro and Birdigo.

Brown ultimately spoke with the developers of Wordatro and Birdigo, with all developers going ahead with their own takes on the wordy roguelike concept—and to great success (the trio has also joined forces to create an epic Steam bundle). What might seem like a cramped little corner of word games has now comfortably fit all three visions, all meaningfully different. Wordatro is a more straightforward riff on Balatro, driven by multipliers and game-changing tile modifiers that allow scores to balloon into the thousands. Birdigo takes a slightly more nuanced approach. It emphasizes shorter words by offering a more limited selection of letters (less than ten at a time), meaning the challenge is rarely in finding a word, but in finding the right word.

This is what’s gotten me so excited about language games as a blossoming niche in thinky design: the idea of deploying the player’s linguistic skills not as an end in and of itself, but as a kind of mechanical launching-off point for all sorts of genre crossovers. Compare Word Play to a game like Chants of Senaar, where the name of the game is entirely to decipher an unknown language. If you knew the language, there wouldn’t be much of a game. But in Word Play, words are only half the story. You also need to play smart, managing resources like plays and refreshes, prioritizing tiles that activate synergies, and ultimately scoring as much as possible. The game uses language almost like a controller.

I set out to find more games that leverage the natural creativity of language as a core mechanic. Moreover, I wanted to consider language not just in terms of vocabulary, but in terms of our intuitions about grammar, meaning, and culture.

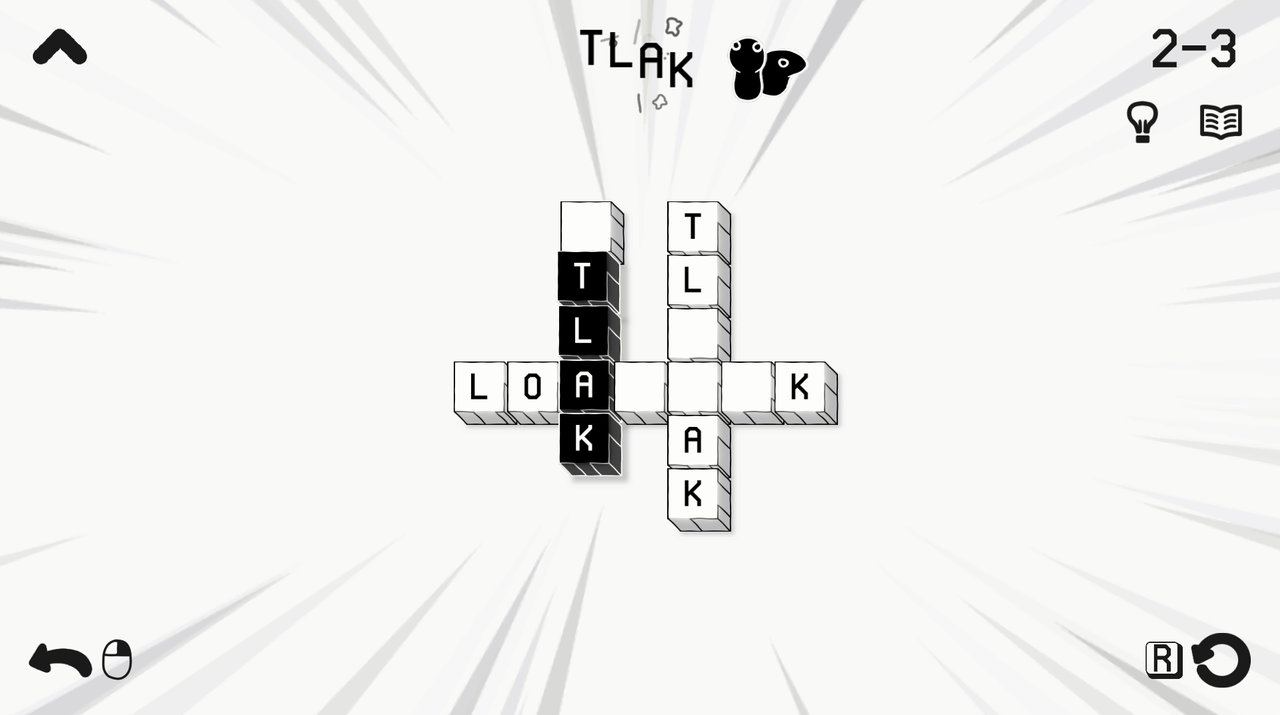

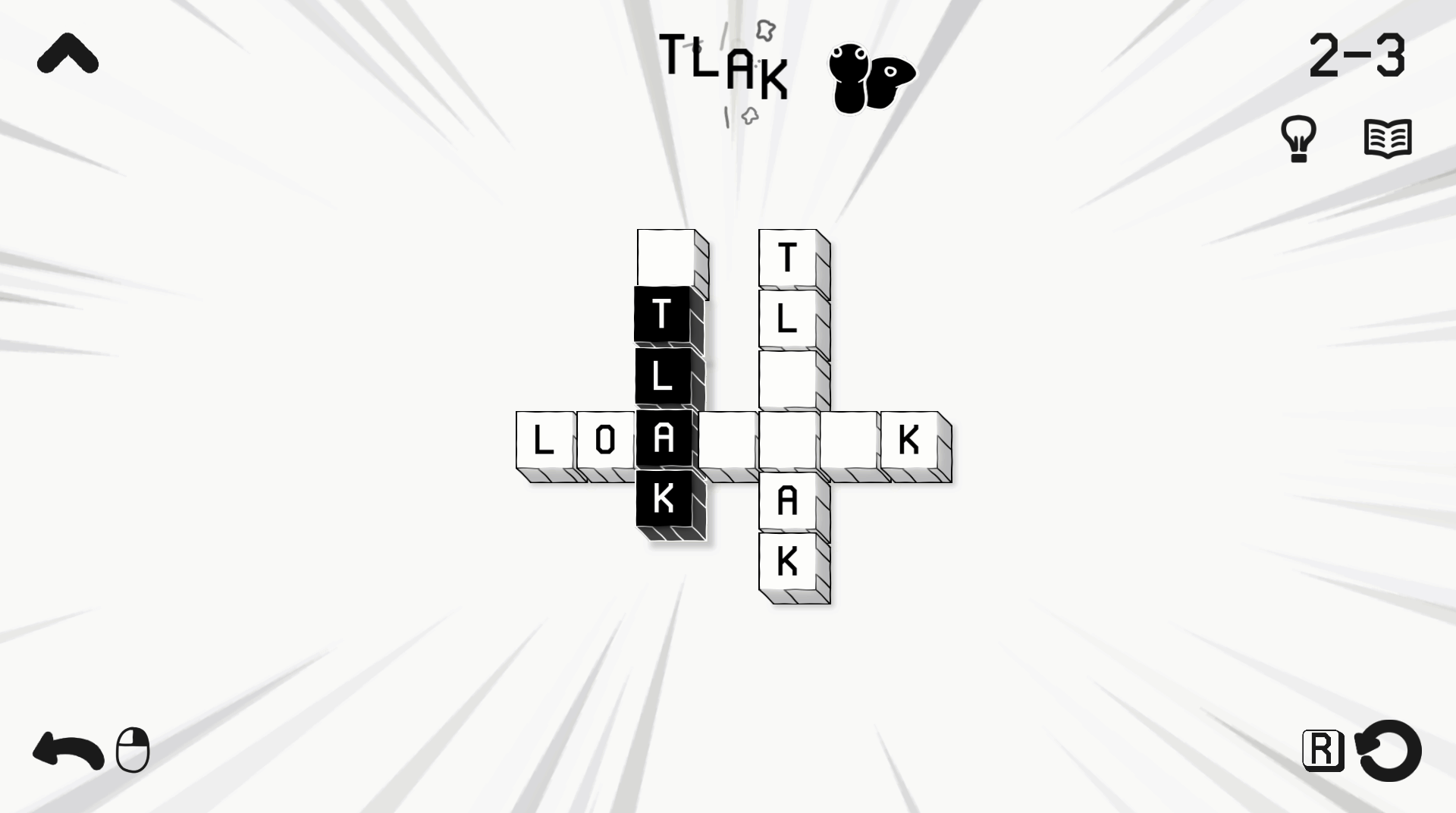

The first game sprang readily to mind since it’s been burned into my phone screen for the past week. LOK Digital is a cryptic word-search puzzler, with the catch that its words are all nonsense. The first word you learn, “LOK,” has the power to black out one tile in the word search. “TLAK” blacks out two adjacent tiles. The goal of each level is to black out every square on the grid using your growing dictionary of words with unique effects. What grabs me about LOK Digital is not that words are particularly hard to find, but that the overlapping spellings of each word obfuscate which word is best to deploy, and when. Should you use TLAK, or remove the L to make the much more useful TA, hoping that the leftover K becomes useful elsewhere? It engages with one of the defining characteristics of human language, which is our ability to remix its constituent parts into infinite possible variations.

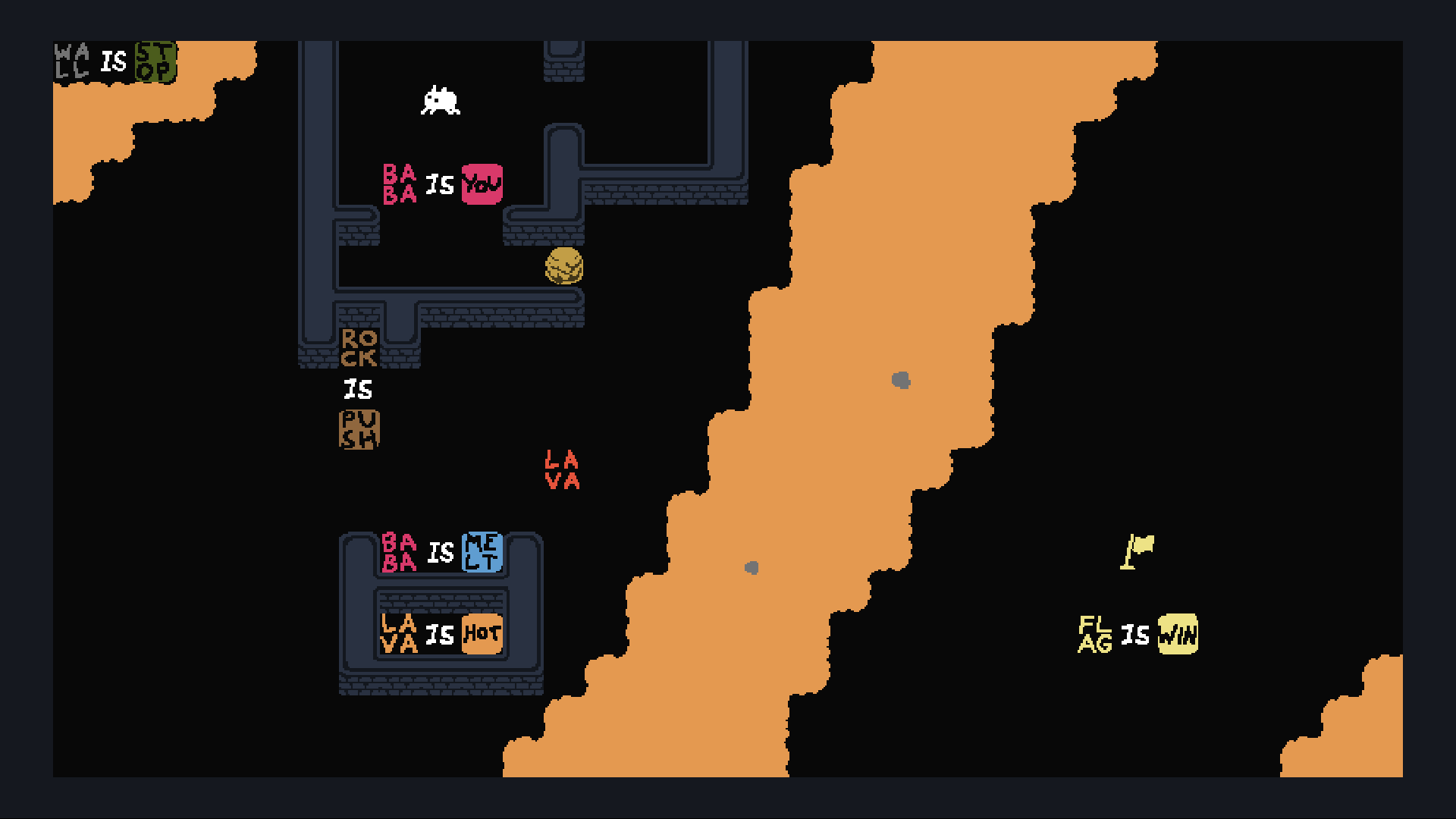

Not only do we remix letters and sounds into words, but our propensity for syntax lets us compose a vast array of sentences from a finite number of words. Baba Is You requires the player to do exactly that. The syntax Sokoban doesn’t simply demand flexibility as its rules are continuously rewritten; its core conceit is the transformational power of language, allowing the player to take part in the construction of each level by creating new sentences. And just like how the demands of grammar constrain our method of communication, the physical space of each level in Baba Is You adds resistance to Baba’s otherwise absolute power.

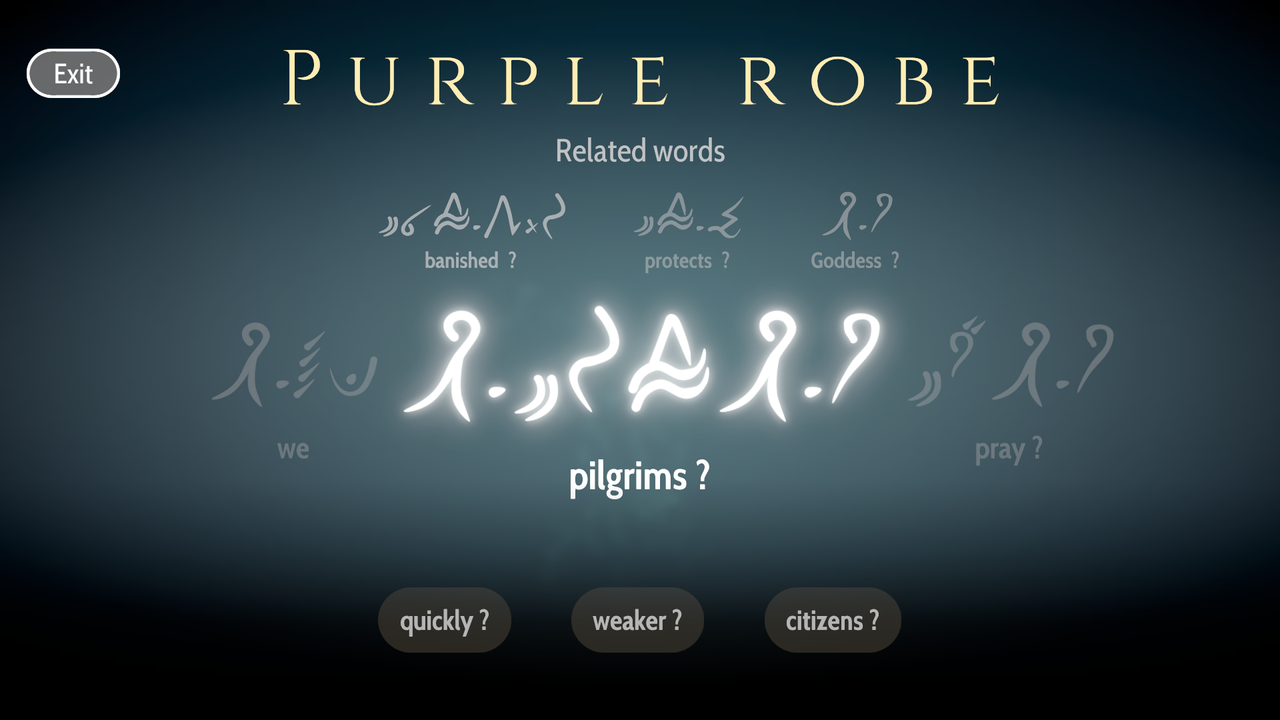

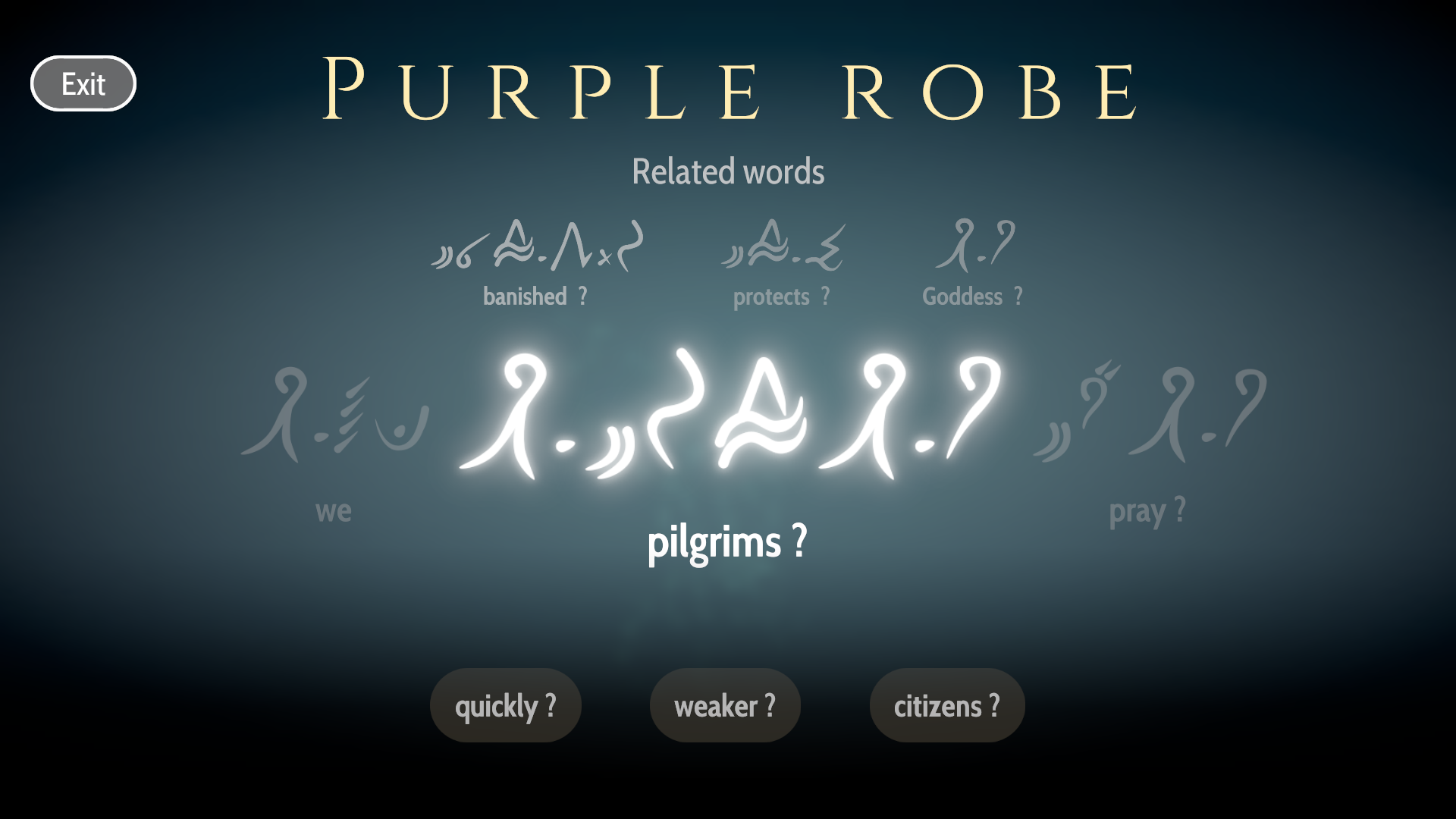

Of course, language is more than the sum of its parts. Its ultimate purpose is to convey culture—a function which Heaven’s Vault explores in a much more freeform way. Developed by Inkle, it’s primarily a sci-fi adventure game following an archaeologist’s quest to track down a missing colleague. But to make any sense of their disappearance, you’ll need to retrace thousands of years of history using inscriptions of a long-dead language. Heaven’s Vault isn’t particularly interested in correcting the player’s assumptions about the meaning of each glyph. There’s no telling whether your understanding of the language is perfect, just as there’s no optimal route through the game’s non-linear narrative. But as you work to patiently uncover the remnants of an ancient civilization through their script, new insights fundamentally change your understanding of the setting and potentially inform your journey.

Philosopher of language J. L. Austin wrote, “We speak of people ‘taking refuge’ in vagueness—the more precise you are, in general the more likely you are to be wrong.” Language resists binaries of correctness and incorrectness. Games that play with language in this way—that “take refuge” in its vagueness—can’t help but adopt some of its creativity. They free the player to express themselves through the game, whether on the level of glyphs, words, sentences, or cultures. For game developers, they come with the added bonus that we all naturally understand the rules of language without the need for tutorialization or manual dexterity. In a gaming landscape saturated with hit-or-miss skill checks, a bit of middle ground provides much-needed space to get the gears turning.