This article is based on a talk I gave at ThinkyCon 2024, titled “Beyond the Screen: The Interplay Between Video Games and Escape Rooms”. That talk is still available to watch on Youtube here, but since I (like most people) hate listening to the sound of my own voice, I wanted to make a typed version instead.

Here’s some information about me: I’m Mairi, an escape room designer. I actually design all sorts of thinky puzzle games, but escape rooms are my favourite. When not playing, I like writing about them. So it’ll come as no surprise that this article is about escape rooms, but more specifically, the origins of the escape room industry and how they intersect with video games.

So, what exactly is an escape room?

An escape room is a physical experience where a team of players are “locked” in a room and must solve a series of puzzles within a certain amount of time to accomplish a goal, typically finding the key to unlock the room.

Sure, the goal isn’t always to unlock the room and escape, but the typical gameplay is centred around finding keys, deciphering clues, rummaging through drawers, pushing mysterious buttons and the like. When you play an escape room you go to a physical location, fully immerse yourself in the designed environment, and solve puzzle-y adventure challenges. It’s an infusion of thinky games and live theatre.

How long have escape rooms been around?

Escape room experts point to different dates as the starting point. It’s hard to agree on exactly which was the first, but it’s not hard to agree that they’re a very, very new industry.

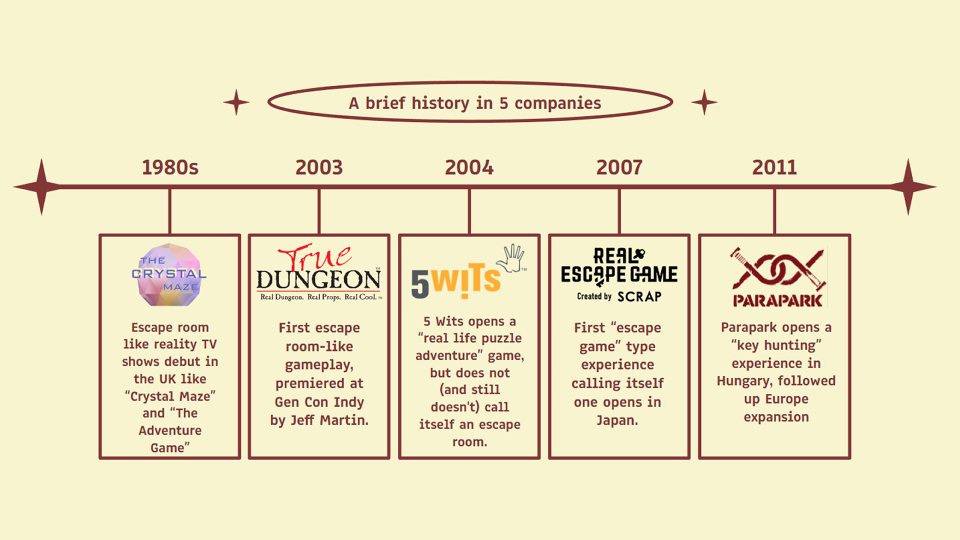

- The 1980s saw the emergence of escape room-like reality TV shows, such as Crystal Maze and The Adventure Game.

- In 2003, True Dungeon by Jeff Martin became the first playable game, premiering at Gen Con Indy.

- One year later in 2004, 5 Wits opens a “real life puzzle adventure” game, however, it doesn’t (and still doesn’t) call itself an escape room.

- In 2007, Real Escape Game created by SCRAP opened in Japan, making it the first officially titled escape room.

Then, a few years later in 2011, escape rooms became mainstream with Parapark opening several key hunting experiences across Europe.

But wait, let’s look at that definition earlier, and if I go in with my invisible marker pen and cross out a few words:

An escape room is a physical experience where a team of players are “locked” in a room and must solve a series of puzzles within a certain amount of time to accomplish a goal, typically finding the key to unlock the room.

That definition sounds more like a video game, and many escape room video games wildly predate their physical counterparts.

Behind Closed Doors (1988): A text-based adventure from the 80s in which you play the Balrog locked in your room by mischief makers.

Myst (1993): A hugely popular game even today, where you wander around an island solving escape room-like puzzles to unlock more of the island.

The 7th Guest (1993): A theatrical puzzle adventure set in a haunted mansion where you go from room to room and solve puzzles and unlock the story.

MOTAS (2001): Then you’ve got The Mystery of Time and Space where you solve riddles and puzzles and escape from locked rooms.

The Crimson Room (2004): Finally, the Crimson Room which despite being a fairly simple Javascript game, is still talked about frequently among escape enthusiasts as the first of its escape room-y kind.

In fact, if we pause on The Crimson Room, the very opening words are:

“I drank too much last night. I thought what time it was now. I felt thirst of the throat. The bed was different from usual. Is this a hotel? No, it does not seem like a hotel. I am shut up. I have to escape.”

That, my friends, is an escape room. But if escape rooms already existed in video game form, why did we go and make physical escape rooms?

The real into the digital, and the reverse

Many of the most popular video games out there can trace their origins back to a real life activity, made digital, and I’m not just talking about PowerWash Simulator (which is a fantastic game, by the way). I’m talking about how tennis turned into Pong, how Lego inspired Minecraft, how commanding an army and invading your enemies in real life became Total War, or how quitting your job and living out your days on a farm became Stardew Valley.

Real life inspiring the digital world isn’t a new thing. My point is that, it just usually happens one way round. But what we’ve seen with escape rooms is that it happened the other way round. Digital experiences that became so popular they spawned a new, real life genre.

When talking about their Real Escape Game, designer Takao Kato of SCRAP explained:

“I was thinking about doing some kind of new event, and the girl sitting next to me said she was hooked on online Escape games, so I just tried to make one. And that’s the truth.”

What did escape rooms steal from video games? What can video games steal back?

So today, we see the video game influence everywhere in the escape room world. For example:

- Rooms that make good use of a single-use inventory system, quests, or checkpoints.

- Real life rooms whose gameplay is structured entirely like a game with live avatars you can control.

- Escape rooms that are quite literally based on video games. It’s not quite an escape room, but London and Seattle are home to the immersive Tomb Raider experience, based on Lara Croft.

So in all, escape rooms haven’t forgotten their thinky game origins, and I love that. But there are a few things escape rooms do differently. Here are a few interesting questions that one poses to the other.

How to direct the players

Unlike in a lot of video games with pop-ups or speech bubbles, escape room designers don’t always get to control exactly what the player is doing, or even what they can do. Instead, escape room designers must draw the player’s attention to clues with creative lighting, sound effects, the position of furniture within a room, or even by the Games Master literally explaining “start here”. It poses an interesting question for designers of both types of games. When you don’t use pop-ups or UI, how do you direct your players?

Effectively using an inventory system

If you’ve ever played an escape room you’ve probably heard the rule that once you’ve used something in the room it’s done. To address this, many rooms even give you a little box to put ‘used’ items in. It’s the most straightforward form of inventory system there is. But unlike in a video game, I can’t carry one hundred health potions, eighteen swords and fifteen thousand cheese wheels. Escape rooms must use this limitation of space and weight creatively. Objects must be used sparingly, and therefore they often become multiple things. What looks like one thing when you first enter a room, might be revealed to be used for something totally different inside. If we as designers are limited by space, what does that mean for puzzle creation?

The first-person experience

Another interesting lesson escape rooms borrowed from thinky games is the player as a character. In a video game the player can play anyone. Human… Animal… The dragonborn who can fly kick bad guys off a mountain. As for escape rooms, not so much. You’re just you. You may have an ability – for example in a recent room I played I got to take on the role of “linguist” meaning I had the secret clue to decoding the alien alphabet. We take it for granted that we can code moments like that more easily in a video game but perhaps they don’t get quite the same result. An “a-ha” moment where you solve the puzzle yourself by hand rather than clicked a button could, in some situations, be more satisfying to solve.

How limitations can lead to more creative puzzles

Unlike a video game, all five senses are involved in an escape room – smell, taste, sight, sound and touch. I’ve played escape rooms set in chocolate factories that smelled (and in parts, tasted) of chocolate. Unfortunately, I’ve never done that in a video game. But unlike in an escape room, in a video game I can soar through the air, control time, and again… Fly kick bad guys off mountains. Designers face many limitations, but with a little creativity, limitations can spawn some very cool thinky puzzles. No matter what sort of thinky game you’re designing, the takeaway for designing for one or the other is to think creatively about the rules of the constructed world. Maybe you can’t do a taste puzzle in a video game, but maybe your character consumes items that have different unique effects. Maybe your escape room can’t rewind time, but with some clever trickery you can simulate it by having your players sent back 30 minutes in the past to race against themselves, all whilst they hear their own recorded voices in the next room. Which is a real thing in a real escape room by the way.

What does the future of games beyond the screen have in store?

So in this article, if I’m saying that thinky games beyond the screen are escape rooms, then it’s logical to ask what might come next.

It’s delightful to see so many designers taking other genres of game and doing the same thing that has been done with escape rooms. Let’s talk about Phantom Peak in London, UK. Phantom Peak is an enormous wild west themed world you can explore. It’s full of quests and puzzles that, once completed, give you achievement cards and bonus points. You can explore the world, chat with all the characters and collect all the bonus things. Or you can find the nearest saloon and enjoy a pint of beer for a few hours. It’s like an open-world RPG and it’s yours to explore however you like. The designer, Nick Moran, is one of the best-known escape room designers in the world and he – alongside other creators – are pivoting in style and scale to large-scale immersive experiences like this.

Only a few weeks ago another comparable experience popped up in London called Bridge Command, a self-styled sci-fi adventure in which up to 24 people take on roles on an enormous spaceship and take part in missions. From navigators to engineers to weapons tech – everyone has a part to play. When I’m not playing puzzle games, I enjoy spaceship simulators, so let me tell you this sounds cool.

You’ve also got “Murder Rooms” or “Jubensha” that have recently gained massive popularity in China. There’s a fast-growing, multi-billion dollar industry dedicated entirely to live murder mysteries that feel as if they’re pulled directly from the pages of Agatha Christie. Imagine players dressed up with semi-scripted roles to play in a real-life, first-person drama. Live murder mysteries have been around for decades, but few have become such a runaway commercial success as the Jubensha experiences.

It’s impossible to say exactly what the next ‘big thing’ will be, but the precedent that escape rooms have set as thinky games beyond the screen is clear and they’re inspiring countless activities popping up worldwide. Who knows exactly what we’ll see next?

Leave a comment